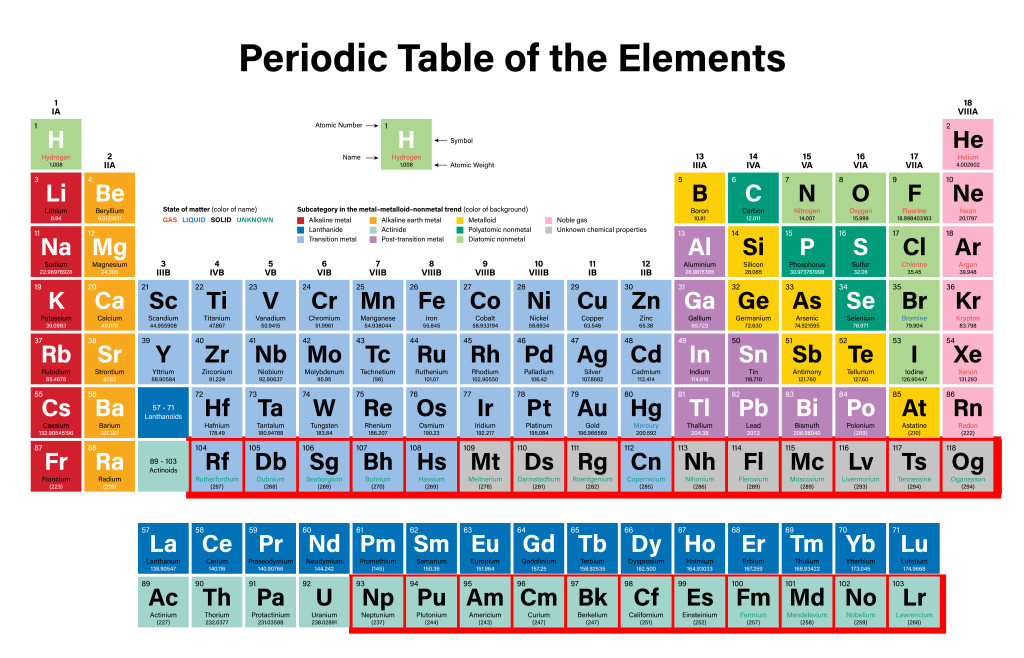

Since 1940, artificially made elements have been added to the periodic table. However, not every discovery is accepted, as there is a criterion that needs to be followed.

The modern periodic table is one of the pioneering inventions in the field of chemistry. This is a nonconventional invention, as it isn’t a physical entity that a single person or a small group has developed; instead, it is the result of the collaborative effort of many scientists, spanning over 130 years and ending with Henry Moseley’s Modern Periodic table in 1913.

Elements in the periodic table are arranged in a manner that makes it easy to study periodic properties like atomic size, electronegativity, and ionization enthalpy at a single glance.

Recommended Video for you:

When Was The Latest Addition To The Periodic Table?

The periodic table has 118 elements, of which 92 are naturally occurring, while the rest are made artificially in a lab. Isn’t it fascinating that we can create something in a lab that only naturally occurs in stellar masses like stars and space clouds!

Of the first 92 naturally occurring elements, Technetium (Z=43) and Promethium (61) have been produced synthetically due to their trace amounts on the Earth. They were eventually detected in distant stars, so they are categorized as naturally occurring. Elements beyond Uranium (Z=92) are completely artificial and are called trans-uranium elements.

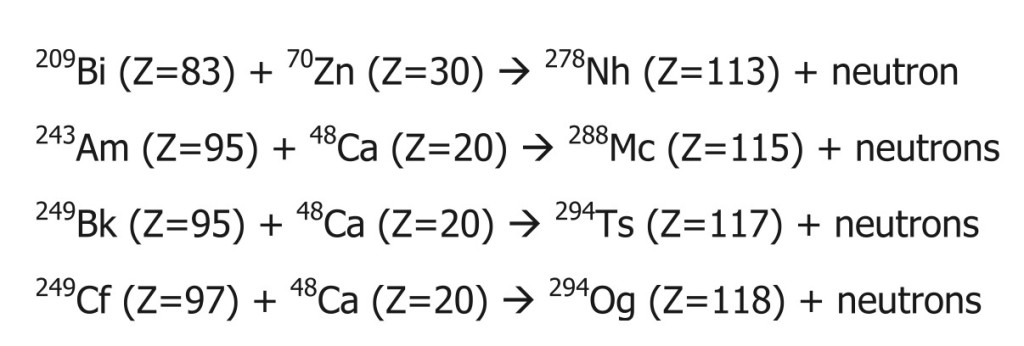

After 1913, scientists continued to add elements that they discovered in their labs and named them following the IUPAC guidelines. The first transuranic element was Neptunium (Z=93), discovered in 1940. After that, elements were added at an average of 2.5 years/element. The latest addition came in 2016 with element 118—Oganesson—named after Russian scientist Yuri Oganessian. This element completed the 7th period and opened the gates for future discoveries for the 8th period of the table. Good luck, future scientists!

How Do Elements Form Naturally?

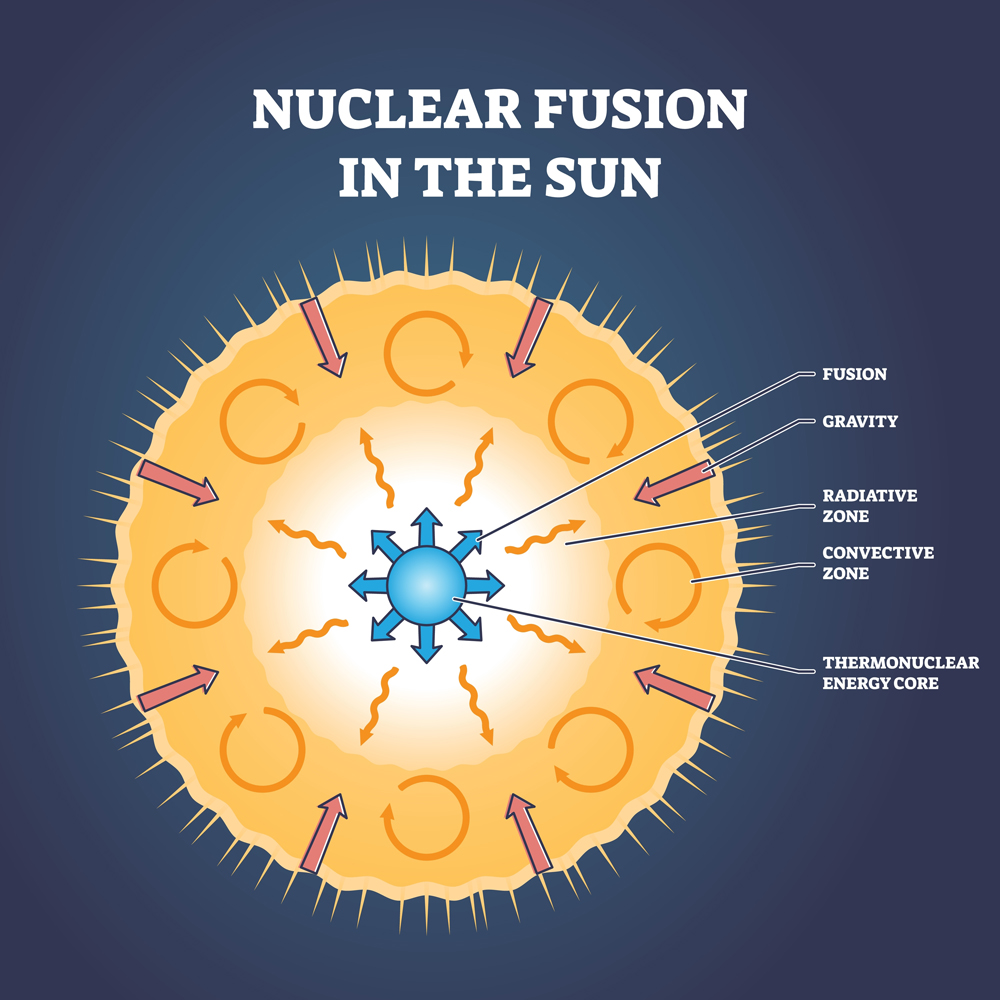

Carl Sagan rightly said, ‘We are all made of star stuff.’ He didn’t mean it metaphorically; he meant it literally, as elements are created inside stars. To create elements is like having Godly powers; you can create life or anything else that you want from them. However, these Godly powers come at a cost: energy and money.

A new element can only be made from existing elements. That is how all elements came into being. The only elements in the space milieu after the Big Bang were Hydrogen (Z=1) and Helium (Z=2). Over the course of a million years, these elements’ nuclei combined in various ways to give us our known elements.

How To Make Elements Artificially

New elements are primarily made through two processes: nuclear fusion and nuclear fission. Fission is used less for creating elements with a large atomic number (Z), because to create these elements, one would need an element with an even larger atomic number, which doesn’t necessarily exist in the universe, so far as we know.

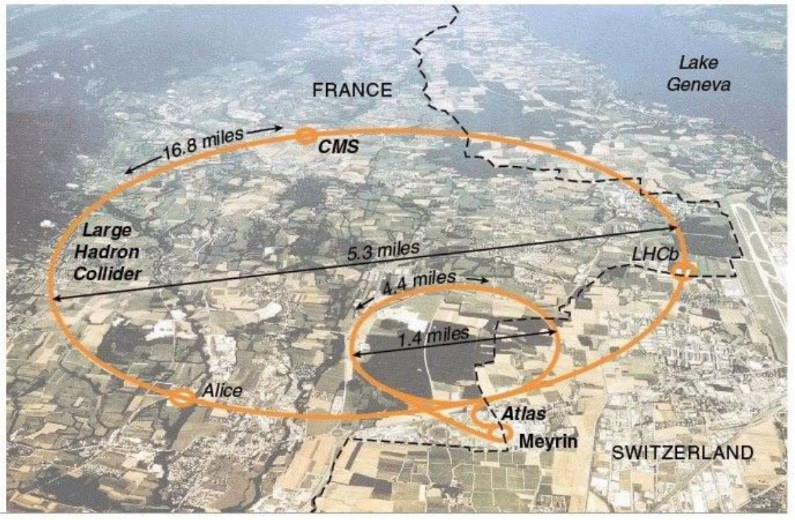

Fusion implies simulating the star’s core in a lab, which is next to impossible. One must generate tremendous pressure of about 265 billion bars to overcome internuclear repulsion and fuse nuclei. Instead, scientists accelerate particles at a fraction of the speed of light and bombard these elements into one another. The collisions generate enough power to overcome the fundamental repulsion.

Cyclotron and Particle accelerators (atom smashers) are built for precisely this purpose. These are heavy experimental setups spread over acres of land in secluded places. Clearly, making new elements is an energy-intensive and costly process.

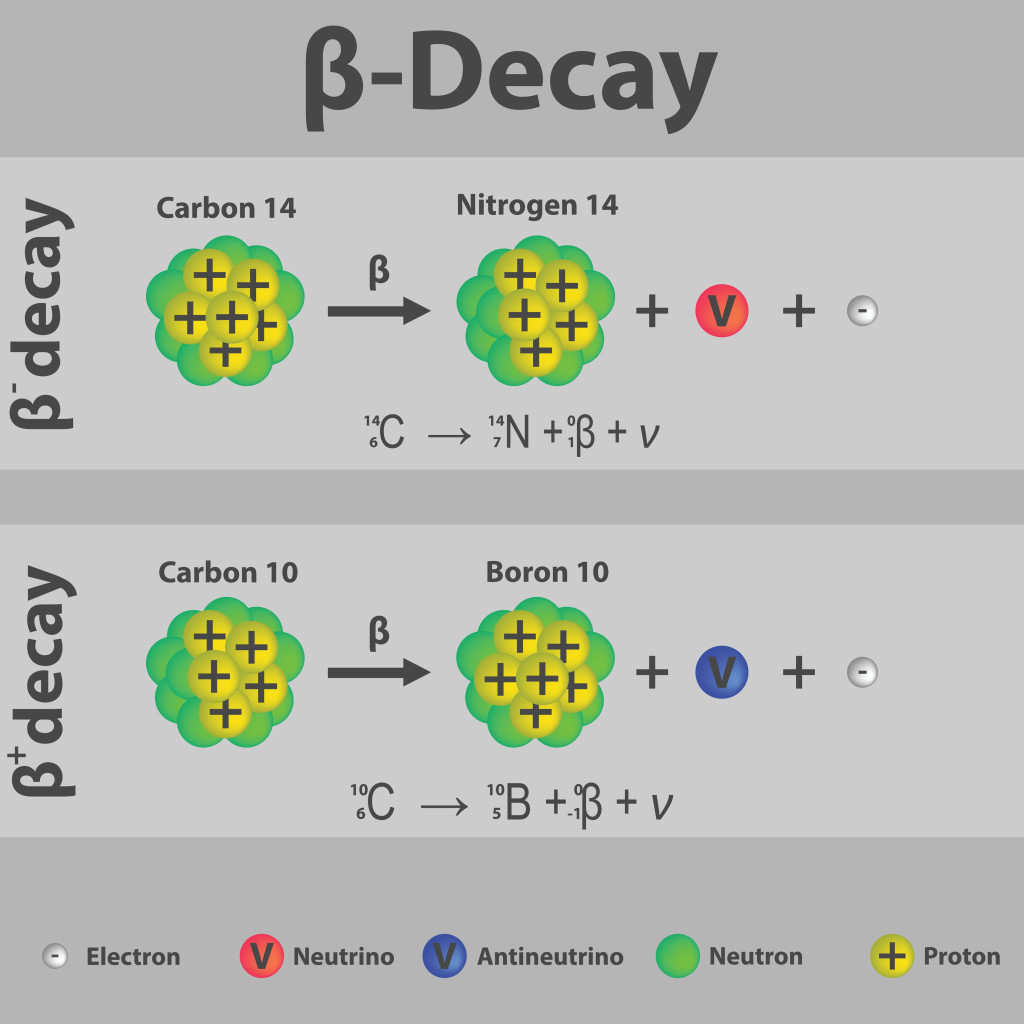

Even if the bombardment is successful, there isn’t a guarantee that you have created a new element.

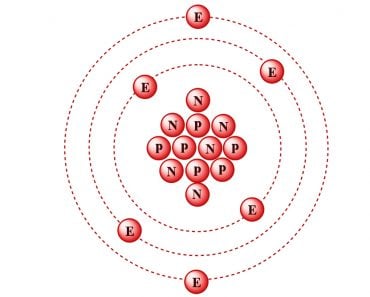

The nuclide is stable if it has the right balance of protons and neutrons, known as the magic number (2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82 protons and 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82 and 126 neutrons.). If it is unstable, it will undergo alpha decay, beta decay, or fission. Only beta decay gives rise to new elements. This decay can take milliseconds, or years, at which point scientists verify with many analytical techniques to see if a new element has truly been formed.

What Are The Criteria For An Element To Be Added?

Simply discovering a new element is only half of the job. After scientists claim to have discovered an element, the JWP (Joint Working Group) of IUPAC and IUPAP stringently verifies the discovery with each of its following guidelines.

- The element should be discovered through experimental demonstration only and have an atomic number that is not present in the periodic table.

- It should exist for at least 10-14 seconds

- The technique used to produce the new element should be reproducible; another technique like this one should bring about the new element in a different laboratory. (There are exceptions to this rule. Interested readers can refer to this paper)

- The experiment giving the new element should have two aspects; the first establishes the physical and chemical properties of the sample containing the suspected new element. This is called characterization properties.

- The second aspect uses properties to demonstrate that the characterization properties are indeed of the unknown element. These are called assignment properties.

- Assignment of A (atomic mass number) can influence the assignment of Z; however, the priority with respect to discovery cannot be denied if the wrong A-assignment does not influence Z.

Since any new element is a matter of groundbreaking discovery, the committee must review each criterion in more detail in the above paper. After the discovery of an element, naming the element is another long process. To give some perspective, Oganesson was discovered in 2002, but was not finally accepted and named in the periodic table until 2016!

Is It Worth Creating New Elements?

When you look at the table of half-lives of the last 9 transuranic elements, you will see that none of these elements can even exist for an hour. The last 3 elements would disappear in the blink of an eye. Proving their existence is like making your friends believe in your ghost story.

| Element | Z | A | Half-life |

| Darmstadtium | 110 | 281 | 4 minutes |

| Roentgenium | 111 | 282 | 10 minutes |

| Copernicium | 112 | 285 | 40 minutes |

| Nihonium | 113 | 286 | 20 minutes |

| Flerovium | 114 | 289 | 1.33 minute |

| Moscovium | 115 | 290 | 1 minute |

| Livermorium | 116 | 293 | 120 milliseconds |

| Tennessine | 117 | 294 | 50 milliseconds |

| Oganesson | 118 | 294 | 5 milliseconds |

The question of whether to continue discovering new elements is a topic of concern amongst chemists and physicists. They also understand the cost and energy that go into making elements. An even more challenging question is whether these elements are useful. The answer to that is a little nuanced.

Scientists have accepted that discovering new elements is time-consuming, chance-driven, and technologically tough. You are either successful or not; even if you create a new element, you probably won’t get a stable nuclide. As a result, most of the latest research is driven towards understating the chemical properties of the existing superheavy elements (Z>100), generating their stable isotopes, and making known heavy elements.

When it comes to potential applications, that answer can only be given after intensely studying each new element’s properties. Since stars are the factories of making elements, one could say that heavier elements could have been formed in distant galaxies. However, they haven’t been detected to date, and they might have vanished, even if they did exist, due to their short half-lives.

Conclusion

Adding a new element to the modern periodic table has its own set of challenges. One might even question the validity of the process. However, if the same concerns bothered Mendeleev and the scientists who followed him, we might have stopped with the 60 elements known at that time. It is only by testing the limits of nature and our understanding that drives these discoveries and gives us hope!

References (click to expand)

- Reedijk, J. (2018, February). Row 7 of the periodic table complete: Can we expect more new elements; and if so, when?. Polyhedron. Elsevier BV.

- Karol, P. J., Barber, R. C., Sherrill, B. M., Vardaci, E., & Yamazaki, T. (2016, January 21). Discovery of the elements with atomic numbers Z = 113, 115 and 117 (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Ball, P. (2019, January). Extreme chemistry: experiments at the edge of the periodic table. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Karol, P. J. (2017, January). The Periodic Table of the Elements: A Review of the Future. ACS Symposium Series. American Chemical Society.

- Seaborg, G. T. (1985, May). Nuclear synthesis and identification of new elements. Journal of Chemical Education. American Chemical Society (ACS).