Table of Contents (click to expand)

Our long-term memory stores the odors we smell as a mental diorama. The olfactory bulb in the brain makes connections with many other brain regions. Associated details such as emotions, people, locations, plants, animals, etc., are stored with it.

One day, as I passed by a bakery, the aroma of warm bread and toasty cookies washed over me, and I suddenly flashed back to a childhood memory of my grandmother baking chocolate chip cookies in the kitchen. It was a cozy and relaxed day. I could recall the sunlight coming through the kitchen window and my grandma’s pink polka dot apron. Her favorite T.V. show was playing in the background, and I could feel the sticky texture of the cookie dough through my little fingers. The smell in that bakery smelt exactly like my grandmother’s cookies.

Isn’t it strange how some smells—even quite ordinary ones—can trigger particular memories? Everyone has that one smell that takes them back through time, reminding them of an experience they once had. Smells, as it turns out, are very important to how we remember things. The smell of cookies from the bakery was so similar to my grandmother’s kitchen that my brain couldn’t help but make the connection.

Recommended Video for you:

The Proust Effect

At the turn of the 20th century, the French writer, Marcel Proust, wrote his masterpiece, the 7-volume series titled ‘In Search of Lost Time’. The book is about how we remember our past; the narrator reminisces in vivid detail about his childhood, while pondering its meaning. One particular scene at the start of the book describes how the taste and smell of madeleines—a small sponge cake—dipped in tea brings back a long-forgotten childhood memory, unleashing an expansive story. The scene is one of the most memorable and famous in the book.

Proust’s penetrating depictions of memories, and how they are triggered unexpectedly by scents, sights, and touches, captivated the imagination of psychologists and neurobiologists; in fact, they termed it the Proust effect.

How Does The Proust Effect Work?

Cretien van Campen, a scientific scholar in the social sciences, defined the Proust effect as “an involuntary, sensory-induced, vivid and emotional reliving of events from the past”.

Our long-term memory stores the odors we smell as a mental diorama. Associated details such as emotions, people, locations, plants, animals, etc., are stored with it. It’s as if the brain makes a mnemonic of that experience using the smell as a key. Smelling such odors again will trigger the recollection of that particular situation. This phenomenon is also termed ‘olfactory memory’.

Intrigued by Proust’s anecdote, scientists decided to further investigate this phenomenon. They designed studies to understand the anatomy of the brain and how it processes sensory stimuli and stores memory. With each study, it became increasingly clear that odors played an important role in memory.

We only know the importance of something once it’s truly lost. Alzheimer’s patients find it difficult to identify odors and this worsens as the disease progresses. One characteristic of Alzheimer’s is that the hippocampus deteriorates. Scientists were able to connect the pieces of the puzzle and determined that the hippocampus is critical to olfactory perception and memory.

However, before I explain how smells trigger memories, let’s dive a bit further into the anatomy of the brain.

The Smelling Brain

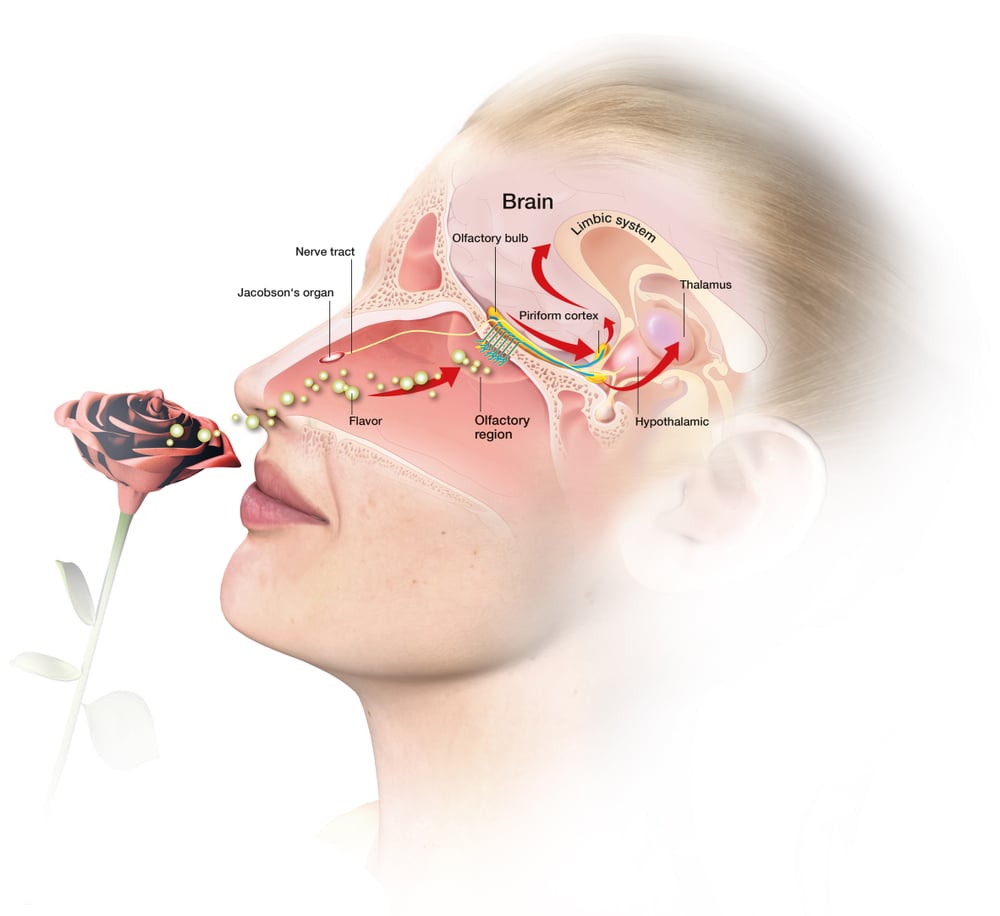

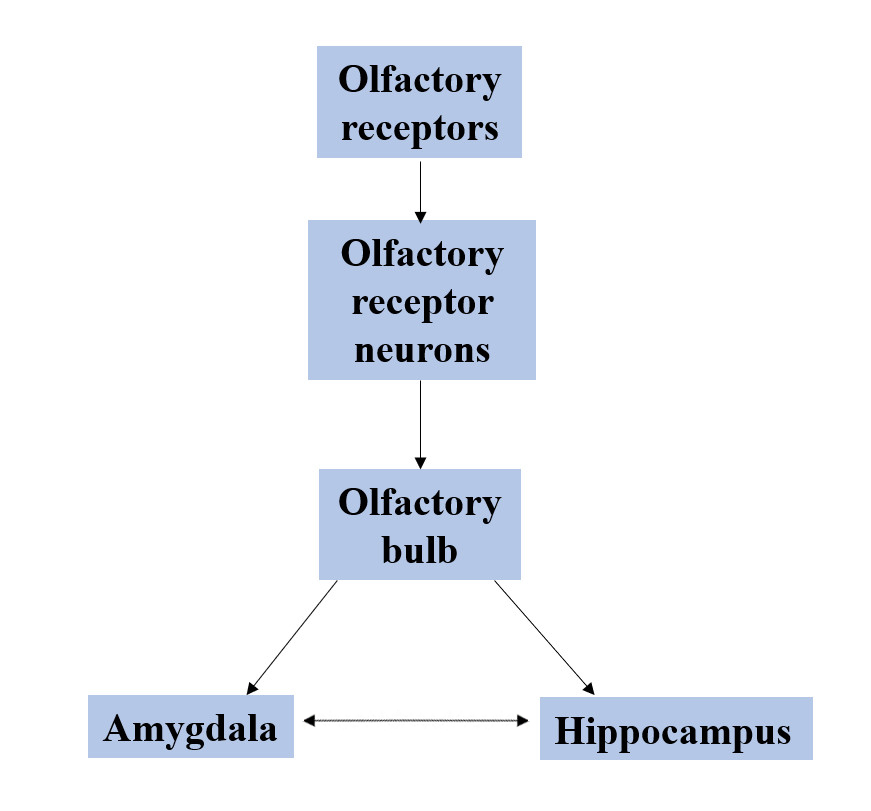

The molecules we inhale enter our nose, where they bump into olfactory receptors. These receptors pass on this information to a part of the brain called the olfactory bulb, which is located behind the forehead. The olfactory bulb decodes this information and identifies what exactly it is that we’re smelling. Neurons then carry this information to the almond-shaped amygdala.

The amygdala is the region of the brain that interprets emotional information, such as happy, sad or funny experiences. From there, the signal moves forward to the hippocampus. The hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped structure that plays a role in learning and forming memories. To summarize, smelling stimulates the amygdala-hippocampal complex.

Imagine that a woman walks into a grocery shop to pick up succulent red strawberries. She takes a big whiff of the strawberry box. Her nose picks up the aromatic compounds that give strawberries their characteristic smell and carries this information in the form of electrical signals to the amygdala-hippocampal complex. This triggers a childhood memory of her and her mother making their weekly Sunday strawberry milkshakes for breakfast.

This is why smelling the shampoo your mom used when you were a kid probably makes you nostalgic about your childhood.

Applied practically, subjecting people to certain smells will cause them to recollect happy memories. This can be used as a therapeutic approach. That feel-good mood we experience while reminiscing in the past has beneficial effects. It bolsters self-esteem and elevates optimism. The connection between one’s past and present grows stronger. It also elicits feelings of social connectedness.

Of course, all of this is very subjective and depends on individual experiences. Individuals interpret odors differently and how they interpret them depends on their exposure to the chosen smells and the associated experiences.

How Is The Proust Effect Used?

Companies have adopted an intriguing style of branding called olfactory marketing. It exploits the Proust effect by inducing a whiff of nostalgia in their targeted demographic. Such products are infused with particular smells that hold meaning and evoke a sense of trust and security associated with that smell. These smells are often trademarked and are known as scent marks.

In the 1990s, a tennis company infused their tennis balls with the smell of grass. They then registered the smell as a scent mark. When consumers open the pack of tennis balls, they are flooded with the feeling or memory of playing on grass. Perfume companies produce multiple scents to entice the olfactory senses of consumers in an effort to increase their popularity.

Of course, this can also be very culture-specific. For some people, cinnamon and nutmeg evoke feelings associated with Christmas. Lavender notes tend to evoke a grandmother’s warmth. Vanilla brings forth comfort and heartiness. Food-related aromas, artificial scents mimicking flavors, are used in packaging. This is done to enhance the food and beverage product experience.

Studies have shown that positive emotions and moods are great for mental health, and good mental health promotes longevity and health. As such, one popular therapeutic method is to use odors to trigger happy and joyful memories. A small part of the comfort that stress eaters get from comfort food comes from the smell. Although our higher brain doesn’t filter olfactory signals, there is a connection between cognitive function and smelling. The more we smell, the more our olfactory network generates newer and stronger connections between brain cells.

So, pay more attention to the smells in your environment. Take more deep breaths and inhale the wide variety of scents that life has to offer!

References (click to expand)

- Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2014, January 23). Scent-evoked nostalgia. Memory. Informa UK Limited.

- Emsenhuber, B. (2011). Scent Marketing: Making Olfactory Advertising Pervasive. Pervasive Advertising. Springer London.

- Aqrabawi, A. J., & Kim, J. C. (2018, July 16). Hippocampal projections to the anterior olfactory nucleus differentially convey spatiotemporal information during episodic odour memory. Nature Communications. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Ernst, A. (2014, December). Review: The Proust Effect: The Senses as Doorways to Lost Memories. Perception. SAGE Publications.

- Wilson, D. A., & Stevenson, R. J. (2003, May). The fundamental role of memory in olfactory perception. Trends in Neurosciences. Elsevier BV.

- Herz, R. (2016, July 19). The Role of Odor-Evoked Memory in Psychological and Physiological Health. Brain Sciences. MDPI AG.

- (2006) Learning to smell: Olfactory perception from neurobiology to .... researchers.mq.edu.au