Hugging or any other physical signs of affection cause the release of the hormone oxytocin in the brain. Oxytocin is responsible for increasing trust and social bonding between people. Oxytocin also decreases anxiety and fear by suppressing the action of the amygdala. This is why hugs make us feel safe and comforted.

Receiving a hug from someone you love can instantly lift your mood. The act of embracing makes us feel loved, comforted, and less alone in the world. But what is it about this strange act of pressing our bodies and wrapping our arms around one another that makes this sometimes harsh world feel bearable?

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do We Hug?

Before addressing the question of why hugs feel so good, it makes sense to investigate why we embrace in the first place.

Social Bonding Hypothesis

One hypothesis that has been pushed forward is the “social bonding” hypothesis. The act of being physically close to another individual might help us form social and emotional bonds with that person. When you consider that humans, and many of the other animals that hug, live in social groups, it suggests that this action is important for bonding with one another. This bonding leads to trusting the members of your group.

Hugging isn’t something that only humans do. Primates, our closest relatives, also create social bonds through actions like hugs and petting. Prairie voles, a species of rodent, are also known to comfort one another through physical touch.

Hugging and other physically intimate actions allow individuals to develop this trust. This social bonding extends to finding a partner to mate with. If you can’t find a partner to reproduce with, you wouldn’t be able to have offspring, which then jeopardizes the survival of your genes. And remember, we are all, to some extent, wired to reproduce.

Since hugging makes reproduction possible, and since trusting your social group mates means that they’ve probably got your back in case you get into any life-threatening trouble, the act of hugging is evolutionarily advantageous.

Knowing all this, we return to our original question—why do hugs feel good? Because of a certain hormone that drives our hugging ways!

Hugging Releases Oxytocin—The Cuddle Hormone—In The Brain

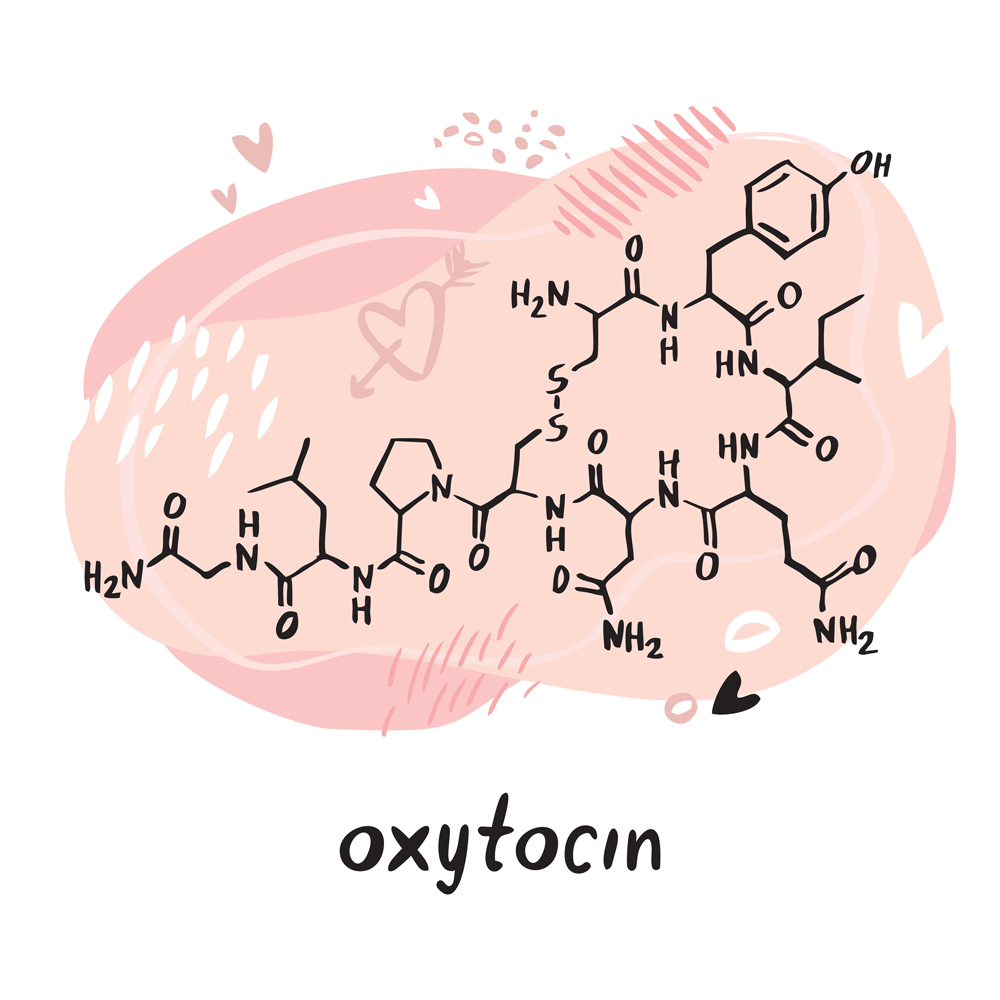

Oxytocin has quite a few aliases, notably the ‘love hormone’ and the ‘cuddle hormone’. This hormone and neurotransmitter (the chemical that helps our neurons communicate) is a small nine-amino acid (the building blocks of life) peptide. It is released from a small gland located in the brain called the posterior pituitary gland.

Its most straightforward functions are to facilitate childbirth (the word oxytocin actually means “swift birth” when translated from Greek) and breast feeding. However, more interestingly for us, oxytocin is also linked to a gamut of lovey-dovey pleasure feelings, such as orgasms, social bonding, connections with parents, and pair bonding (or finding a mate). To put it less scientifically, oxytocin helps us find love, to love someone, and enjoy the love we receive in return! Now the nickname makes a bit more sense…

How Oxytocin Affects The Body And Brain

Oxytocin affects the body and brain in numerous ways. Since we’re only interested in how it makes hugs more pleasurable, we’ll restrict our discussion to that aspect.

Oxytocin works through its receptors. After oxytocin is released from the pituitary gland and into the brain, it binds to oxytocin receptors. You can think of this hormone-receptor interaction like two complementary puzzle pieces fitting together. Oxytocin will only bind to its correct receptor.

Oxytocin receptors are present on the neurons of many different brain regions, such as the hypothalamus, many areas of the limbic system, and in areas of the brain stem. When oxytocin molecules bind to receptors on the neurons present in these brain regions, they cause the neurons to fire, which signals other parts of the brain and body to make certain changes.

Interestingly, oxytocin’s “hug effects” don’t come from what it activates, but rather from what it suppresses. Oxytocin suppresses the activity of various brain regions, one of which is the amygdala.

The amygdala is a small almond-shaped part of the brain located in the limbic system. It controls many functions, but is largely responsible for our fear, aggression, reward and sexual desires.

By suppressing the amygdala, oxytocin reduces our feelings of fear and anxiety. This lack of anxiety makes us feel safe and loved. Some would describe this as a feeling of happiness.

A study published in 2004 in the journal Biological Psychology found that when partners hug, it causes a release of oxytocin that lowers blood pressure, which makes us feel calmer. A decrease in blood pressure is also good for cardiovascular health.

A 2016 study found that hugging reduces stress and might help decrease the likelihood of infection. Stress is known to weaken the immune system, which increases the probability of getting sick. However, perceived social support, as expressed through hugs, could decrease stress.

Why Some People Don’t Like Hugging

Though we’ve been speaking a great deal about how fantastic hugs are, it isn’t for everybody! For some people, hugs just aren’t comfortable or downright unpleasant. After all, life isn’t a one-size-fits-all deal.

For non-huggers, the matter could boil down to their childhood. Children from households where hugging or physically displaying affection wasn’t common, or was even frowned upon, might find hugs uncomfortable in their adult life as well. Children learn social language through their parents and family. When parents play with their child, hug and cuddle them, it all leads to positive bonding and a less anxious child.

Culture matters in this regard too. In some cultures, displaying signs of physical affection is common. In 1966, the eminent psychologist Sidney Jourard counted how many times couples touched each other during a conversation in San Juan (Puerto Rico), London, Paris, and Gainesville (Florida). He writes in his research paper titled ‘An Exploratory Study of Body‐Accessibility‘, “the ‘scores’ were, for San Juan, 180; for Paris, 110; for London, 0; and for Gainesville, 2.”

In certain situations, it simply isn’t appropriate to hug someone. We only like to receive hugs from the people we know or might want to know in a emotionally intimate capacity. Thus, a hug from a dear friend or a colleague that we’ve known for a while might be welcome, but a hug from a banker who approves your loan would probably make us feel more discomfort than trust.

Simply knowing a person isn’t enough to go in for the “real thing”. It is always best to get consent. Ask whomever you wish to embrace if they would be welcome to it. If they say yes, then go ahead and give them a tight, rib-crunching hug and enjoy the good feelings that start to flow!

References (click to expand)

- (2005) frequent partner hugs and higher oxytocin levels are linked to .... mzellner.com

- Mottolese, R., Redouté, J., Costes, N., Le Bars, D., & Sirigu, A. (2014, May 27). Switching brain serotonin with oxytocin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Gordon, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Leckman, J. F., & Feldman, R. (2010, December). Oxytocin, cortisol, and triadic family interactions. Physiology & Behavior. Elsevier BV.

- Seshadri, K. (2016). The neuroendocrinology of love. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Medknow.

- Forsell, L. M., & Åström, J. A. (2012, January). Meanings of Hugging: From Greeting Behavior to Touching Implications. Comprehensive Psychology. Ammons Scientific.