Table of Contents (click to expand)

Too tired to read? Listen on Spotify:

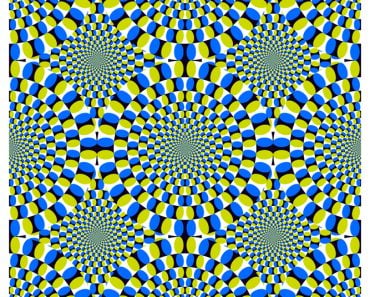

The Wagon wheel effect is an optical illusion that is caused by the brain processing images in a certain way. The brain fills in the voids between images by creating an illusion of continuous movement between similar images. Therefore, if the wheel rotates most of the way along one frame (image) to the next, the most apparent direction of motion for the brain to comprehend is backwards.

Ever observed that a car’s wheel spins backwards when it moves fast? Relax, it isn’t supernatural. There’s a perfectly reasonable scientific explanation to it..

We have all observed this strange visual phenomenon before. A car wheel appears to be spinning backwards, even though we know that it is doing exactly the opposite!

At first, when a car begins to speed up, everything seems normal. The car’s wheels are spinning just as one would expect. However, as soon as the wheels start gaining considerable speed, an anomaly occurs.

At a certain point, the spin of the wheels appears to slow down gradually, and then, for a brief moment, it stops completely. When it resumes, the spin is moving in the opposite direction. We can clearly observe that the car wheels seem to be spinning backwards (opposite to its direction of motion).

Recommended Video for you:

Is This An Optical Illusion Or A Real Phenomenon?

Actually, it’s a bit of both, and is known as the Wagon wheel effect.

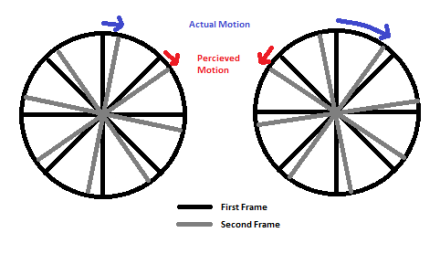

This effect is observable mainly on television or in movies. The cameras used in movies don’t capture continuous footage, but rather many images per second. Usually, this capture rate is approximately 24 to 50 frames per second. Our brain fills in the voids between these images by creating an illusion of continuous movement between similar images.

Therefore, if the wheel rotates most of the way along one frame (image) to the next, the most apparent direction of motion for the brain to comprehend is backwards. This is the explanation for the phenomenon in movies.

However, we also observe the same illusion in real life. Surely we can’t blame shutter speed for that too!

So What’s The Reason?

There are two theories currently rolling around in this particular field of study…

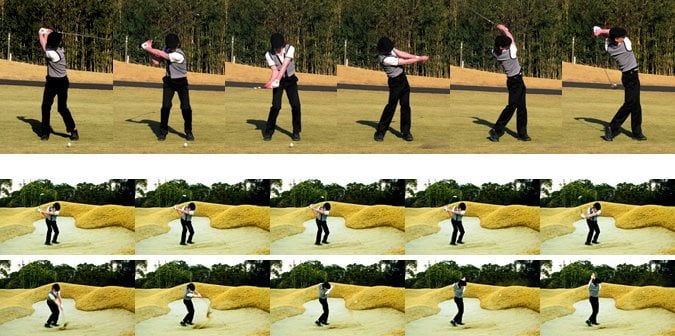

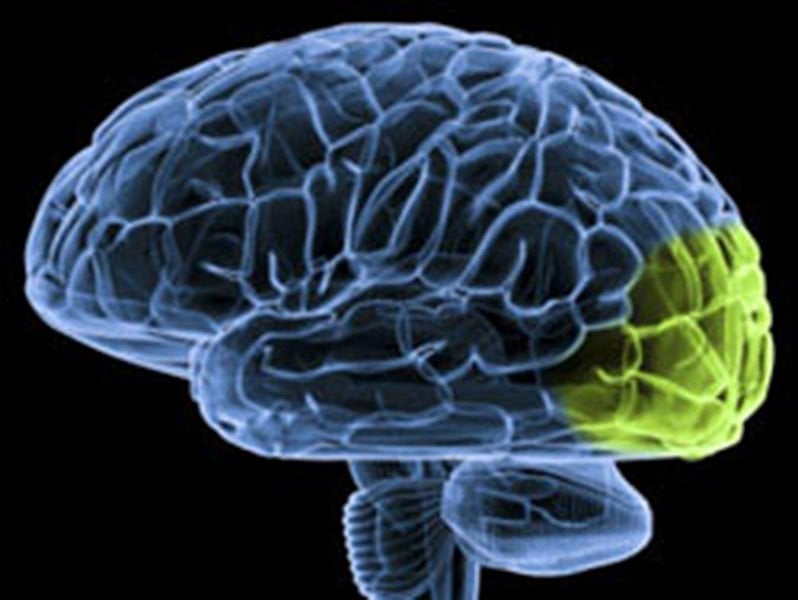

1) Visual Cortex

The visual cortex, which acts almost like a movie camera, processes sensory input in temporal packets, taking a series of snapshots and then creating a continuous scene. Perhaps our brain processes these still images in the same way as it does the frames in a movie, and the mistake in perception results due to a limited frame rate. This occurs when the light is strobed (not continuous).

2) Perceptual Rivalry

According to this theory, adjacent spinning wheels are observed by people as if they were switching direction independently of each other. According to the movie camera theory, the two wheels should not behave differently, as the frame rate is the same for everything in the visual field.

This has led some scientists to a theory that explains the effect as a result of perceptual rivalry, which occurs when the brain creates two different interpretations of one situation, as a way to explain an ambiguous (something that isn’t clear) scene. The perception that is dominant is what we “believe” (in this case, that the wheel is actually spinning backwards).

So, it’s true, this whole thing has more to it than meets the eye, because science always has a hand in the phenomena we observe!

Here’s a detailed explanation of this bizarre anomaly.