Table of Contents (click to expand)

Saccadic masking is a phenomenon that occurs when the brain blocks out visual information during rapid eye movements, in order to prevent motion blur. This can make it difficult to see objects that are in the process of moving, or to track objects that are moving quickly.

Recommended Video for you:

Saccadic Masking

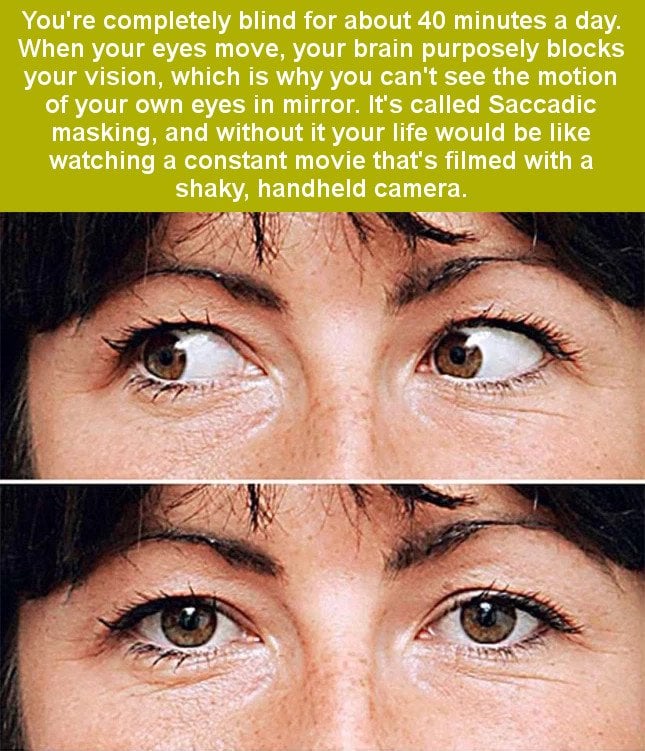

When our eyes move, the brain purposely blocks our vision. This is the reason why you can’t see the motion of your eyes in a mirror. This is known as saccadic masking. The brain selectively blocks visual processing during eye movements to suppress motion blur. Without this suppression, the blur would become a frequent source of distraction, nausea rather.

Saccades

If you have ever tried to move your eyes and catch them in their stride while brushing in front of your mirror, you might have discovered that doing so is impossible. No matter how hard you try, or how rigorously you scrutinize, it cannot be done. While, strangely, the movement of your staggering eyes is quite conspicuous in front of a camera. These rapid eye movements are formally known as saccades. And the absence of their perception or the inability to perceive your saccades is called saccadic masking or suppression.

Why Does The Brain Do It?

Evolution has made us all empiricists. We heavily rely on our senses, which work in synchrony and contrive our perception. One of these indispensable senses is vision. In sobriety, it provides a stable, reliable and continuous field of vision that sweeps copious spaces with high resolution. Its reliability is unquestionable, for it works unhindered, despite the constant movement of our eyes and the twisting and turning of our heads.

Of course, I’m sure by now that you know its design is not exactly infallible. Our eyes are often preyed on by visual illusions, which makes the design of our eyes really intriguing. Saccadic masking is another such peculiarity, something that has perplexed psychologists for a century. The brain selectively blocks visual processing during eye movements to suppress motion blur. Without this suppression, the blur would become a frequent source of distraction, nausea rather.

The phenomenon was discovered by Erdmann and Dodge in 1898 in an unrelated experiment, where they concluded that observers could never detect the movement of their own eyes. For microseconds, the brain makes us effectively blind by snubbing any visual input to obviate dizziness resulting from the blur that these movements would cause. Owing to saccadic masking, the brain becomes so shamelessly oblivious to anything in this small window that people often miss bright flashes or entire movement of objects.

Discrete Images

If the brain did not mask the intermittent blurs, then rapid eye movements would provide the first-person visual of a scene transition in a cartoon or How I Met Your Mother everytime you turn. This is evident when viewing the blades of a rapidly rotating fan or the distorted trees that we witness from a fast-moving train. However, one can obtain a stable image during saccades by artificial means. One can get rid of both the blur and saccadic masking by looking in the trailing object’s direction.

Saccadic Masking Test

Researchers tested this by asking subjects to look in a fast-moving pattern’s direction, a pattern previously unintelligible when perceived while the subject was stationary, and the pattern was whizzing by him. After carefully following the pattern, the subjects could recognize it, albeit only for a short period of time, just like one can track a fan’s blade temporarily.

As the object continues to move, the cognitive suppression is brought back into the game. It seems like it only lasts between 20-100 microseconds. The consensus is that they last for 50 microseconds, but studies differ in their results. Furthermore, the onset of suppression depends on the speed of a saccade itself. Angular eye speeds during a saccade can reach 10 degrees/sec to 300 degrees/sec. Notably, the velocity is positively related to the size of the movement; the bigger the saccade, the faster the gates are shut.

Therefore, it seems that the brain establishes a visual continuity, despite our eye movements, by projecting a series of discrete images. The suppressed blur is preceded by the last image and followed by the next image. However, the fact that the brain casts an image it hasn’t seen before is mind-boggling! What kind of sorcery is this?

Ironically, this eccentricity is actually another of our brain’s limitations (or a perk? That’s for you to decide.) – its ineptitude at keeping time. The brain has no absolute clock, and the flow of time is subjective. During movements, the brain freezes its internal clock and waits for the next image. Then, it fast-forwards this clock and syncs it with the real world. This is exactly what happens during chronostasis – a temporal illusion where an impression usually followed by another appears to be extended longer than its expected time. Chronostasis is the same phenomenon that occurs when the second hand of an analog clock appears to be absurdly stuck on a number for a second longer than its usual tick.

Despite its benefits, saccades represent an evolutionary flaw. The advancement of technology has done to us what roads did for tigers. Saccadic masking evolved to make vision more accurate and stable for our ancestors who lived in the African Savannah, but the momentary blindness while driving at 60 mph in California often beckons an accident. When we move our eyes from the road to focus on a blurred object in our peripheral vision, saccadic masking could cause you to overlook an object in the angular sweep between the two fixations, say, a cyclist, leading to a horrific accident. This dreadful phenomenon becomes more probable for smaller or more unnoticeable objects.

As for why, unlike mirrors, cameras can capture your eye movements is that the camera projects what it sees with a delay, a delay that is large enough to surpass the time of suppression. Basically, by the time your eyes appear to stagger, the saccadic masking is already executed.

Saccadic Masking

When our eyes move, the brain purposely blocks our vision. This is the reason why you can’t see the motion of your eyes in a mirror. This is known as saccadic masking. The brain selectively blocks visual processing during eye movements to suppress motion blur. Without this suppression, the blur would become a frequent source of distraction, nausea rather.

Saccades

If you have ever tried to move your eyes and catch them in their stride while brushing in front of your mirror, you might have discovered that doing so is impossible. No matter how hard you try, or how rigorously you scrutinize, it cannot be done. While, strangely, the movement of your staggering eyes is quite conspicuous in front of a camera. These rapid eye movements are formally known as saccades. And the absence of their perception or the inability to perceive your saccades is called saccadic masking or suppression.

Why Does The Brain Do It?

Evolution has made us all empiricists. We heavily rely on our senses, which work in synchrony and contrive our perception. One of these indispensable senses is vision. In sobriety, it provides a stable, reliable and continuous field of vision that sweeps copious spaces with high resolution. Its reliability is unquestionable, for it works unhindered, despite the constant movement of our eyes and the twisting and turning of our heads.

Of course, I’m sure by now that you know its design is not exactly infallible. Our eyes are often preyed on by visual illusions, which makes the design of our eyes really intriguing. Saccadic masking is another such peculiarity, something that has perplexed psychologists for a century. The brain selectively blocks visual processing during eye movements to suppress motion blur. Without this suppression, the blur would become a frequent source of distraction, nausea rather.

The phenomenon was discovered by Erdmann and Dodge in 1898 in an unrelated experiment, where they concluded that observers could never detect the movement of their own eyes. For microseconds, the brain makes us effectively blind by snubbing any visual input to obviate dizziness resulting from the blur that these movements would cause. Owing to saccadic masking, the brain becomes so shamelessly oblivious to anything in this small window that people often miss bright flashes or entire movement of objects.

Discrete Images

If the brain did not mask the intermittent blurs, then rapid eye movements would provide the first-person visual of a scene transition in a cartoon or How I Met Your Mother everytime you turn. This is evident when viewing the blades of a rapidly rotating fan or the distorted trees that we witness from a fast-moving train. However, one can obtain a stable image during saccades by artificial means. One can get rid of both the blur and saccadic masking by looking in the trailing object’s direction.

Saccadic Masking Test

Researchers tested this by asking subjects to look in a fast-moving pattern’s direction, a pattern previously unintelligible when perceived while the subject was stationary, and the pattern was whizzing by him. After carefully following the pattern, the subjects could recognize it, albeit only for a short period of time, just like one can track a fan’s blade temporarily.

As the object continues to move, the cognitive suppression is brought back into the game. It seems like it only lasts between 20-100 microseconds. The consensus is that they last for 50 microseconds, but studies differ in their results. Furthermore, the onset of suppression depends on the speed of a saccade itself. Angular eye speeds during a saccade can reach 10 degrees/sec to 300 degrees/sec. Notably, the velocity is positively related to the size of the movement; the bigger the saccade, the faster the gates are shut.

Therefore, it seems that the brain establishes a visual continuity, despite our eye movements, by projecting a series of discrete images. The suppressed blur is preceded by the last image and followed by the next image. However, the fact that the brain casts an image it hasn’t seen before is mind-boggling! What kind of sorcery is this?

Ironically, this eccentricity is actually another of our brain’s limitations (or a perk? That’s for you to decide.) – its ineptitude at keeping time. The brain has no absolute clock, and the flow of time is subjective. During movements, the brain freezes its internal clock and waits for the next image. Then, it fast-forwards this clock and syncs it with the real world. This is exactly what happens during chronostasis – a temporal illusion where an impression usually followed by another appears to be extended longer than its expected time. Chronostasis is the same phenomenon that occurs when the second hand of an analog clock appears to be absurdly stuck on a number for a second longer than its usual tick.

Despite its benefits, saccades represent an evolutionary flaw. The advancement of technology has done to us what roads did for tigers. Saccadic masking evolved to make vision more accurate and stable for our ancestors who lived in the African Savannah, but the momentary blindness while driving at 60 mph in California often beckons an accident. When we move our eyes from the road to focus on a blurred object in our peripheral vision, saccadic masking could cause you to overlook an object in the angular sweep between the two fixations, say, a cyclist, leading to a horrific accident. This dreadful phenomenon becomes more probable for smaller or more unnoticeable objects.

As for why, unlike mirrors, cameras can capture your eye movements is that the camera projects what it sees with a delay, a delay that is large enough to surpass the time of suppression. Basically, by the time your eyes appear to stagger, the saccadic masking is already executed.

References (click to expand)

- Moore, T., Tolias, A. S., & Schiller, P. H. (1998, July 21). Visual representations during saccadic eye movements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Irwin, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Sun, J.-. shi . (1988). Visual masking and visual integration across saccadic eye movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. American Psychological Association (APA).

- Saccadic masking - Wikipedia. Wikipedia