Table of Contents (click to expand)

Holobiont is a collective term for a host organism, typically a eukaryote, and the variety of other species that live on, near or within it, jointly forming an ecological unit.

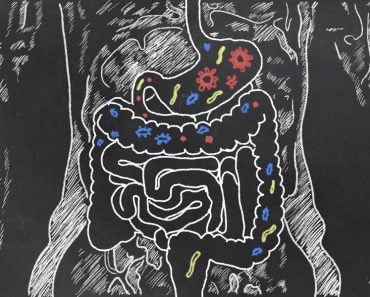

When you look at a human being, you think of it as an individual organism from a single species, but if you zoom in a few million times, you will find that there are many other species living on and inside every human being. We have an entire microbiota of bacteria that can affect health on our skin alone—more than 500 different types! And on the inside of our bodies, we have another 500-1,000 types of bacteria in the gut, along with the many viruses that may be present in our system, both acute and asymptomatic (known as the virome). There is also an estimated 80 different genera of fungi found on the human body, mostly on the feet and between the toes!

Clearly, a human being is intimately connected to plenty of other microscopic species, some of which are dangerous, while others are essential for keeping us healthy and balancing our microbiome. Together, human beings (as the host) and the many microscopic species living in and on the body (bionts) can be called a holobiont!

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Holobiont?

Human beings might be the most widely studied holobiont, but it is surely not the only example. A holobiont is any agglomeration of a host, microbiome, virome, and other related organisms that each function together as a whole. Thirty years ago, no one had heard of a holobiont because the term wasn’t coined until 1991, by evolutionary theorist Lynn Margulis. It was initially applied to limited partnerships, such as various fungi and algae that combine in lichen-covered rocks, and other common symbiotic relationships, but was soon applied to much more complex ecological units, such as coral reefs!

A reef comprises the coral animal itself, the algal symbionts that grow and function on the coral, as well as all the bacterial and microbial bionts relying on these other organisms to survive and thrive. The idea of a holobiont has also inspired the concept of a hologenome, meaning the collective genetic character of all aspects of a holobiont. The hologenome theory of evolution views organisms as communities, and their genetic code as a mutually interacting and evolving genome.

In some cases, this may be the case, as symbiotic relationships often result in coevolution, and such progress may be present in specific host-biont pairs, but some holobionts comprise hundreds of different microorganisms and species, all of which interact in different ways. For clarity, a hologenome includes: 1) the host and symbiont genes that alone or together affect a holobiont genome; 2) the coevolved host and symbiont genes that affect the holobiont phenotype; and 3) host and symbiont genes that don’t affect the holobiont phenotype.

Every symbiont and biont has a slightly different method of interaction with the host, ranging from parasitic to mutualistic, and may also have very different levels of partner fidelity (which must be very strong for coevolution). Some of these relationships may be temporary, or antagonistic, or established in broadly differing ways. The idea that all of these individual genomes will consistently evolve as a holobiont unit is unlikely; in other words, natural selection will work at different levels, and at different rates, for constituent members of the holobiont.

Holobiont Examples

Some of the most widely studied examples of holobionts are human beings and coral reefs, but in fact, all animals and plants are holobionts, as every species we know of maintains some sort of microbiome and close-knit relationships with other microorganisms. In the past two decades, a significant amount of research attention has shifted to studying holobionts and the effects of such complex arrangements on fitness, illness, selection, and survival.

Holobiont Vs. Symbiote Vs. Microbiome Vs. Superorganism

Given that holobiont is a relatively new concept in biology, it is only natural that some people confuse or conflate it with other related concepts. For example, a microbiome is the collective name for the ecological communities that live on, in or near an organism, including pathogenic, commensal and symbiotic partners. This term, therefore, does not include the host itself, which is typically a eukaryotic organism. A symbiote is one member of a symbiotic relationship, in which both members benefit from the partnership. A holobiont does contain symbiotic relationships, but also comprises parasitic, opportunistic, mutualistic and commensal partnerships between the dozens or hundreds of constituent members.

Holobionts are often confused with superorganisms as well, but there is a very clear difference between them. A superorganism tends to consist of many individual members, such as an ant colony or beehive. These individuals work together, with different types performing specialized functions, much like the cells of a traditional organism. Typically, a very small percentage is responsible for reproduction, and the failure of one area/specialization of the superorganism will likely result in the failure of the remainder, similar to a spreading cancer in a single organism.

A Final Word

The concept of holobionts is a perfect example of how our understanding of biology continues to evolve over time. Although these types of interwoven relationships have existed for billions of years, the significance of these interactions is only being explored now! Not to be confused with superorganisms, microbiomes or basic symbiotic relationships, a holobiont is an ecological community of interconnected members that includes the eukaryotic host and a nearly limitless number of microbiotic members!

References (click to expand)

- Haag, K. L. (2018, March 1). Holobionts and their hologenomes: Evolution with mixed modes of inheritance. Genetics and Molecular Biology. FapUNIFESP (SciELO).

- I, holobiont. Are you and your microbes a community or ....

- Douglas, A. E., & Werren, J. H. (2016, May 4). Holes in the Hologenome: Why Host-Microbe Symbioses Are Not Holobionts. (M. J. McFall-Ngai & R. J. Collier, Eds.), mBio. American Society for Microbiology.

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A., & Dufresne, A. (2015, February 5). The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytologist. Wiley.