Table of Contents (click to expand)

For the 60 years between 1859 and 1919, even the most brilliant astronomers were adamant that there existed a planet between Mercury and the Sun. It took 60 years and the genius of Albert Einstein to vanquish their obstinacy and, in the process, repudiate a theory fortified by almost 400 years of time and dogma.

For the 60 years between 1859 and 1919, even the most brilliant astronomers were adamant that there existed a planet between Mercury and the Sun. It took 60 years and the genius of Albert Einstein to vanquish their obstinacy and, in the process, repudiate a theory fortified by almost 400 years of time and dogma. Einstein confounded the theory of gravity bestowed upon us by the man who was then considered a demigod of physics, Sir Isaac Newton.

Recommended Video for you:

The Discovery Of Neptune

On the solitary night of March 13, 1781, astronomer William Herschel, with the telescope he built himself, set out on his usual venture of surveying stars. However, the night was anything but usual. On that night, as the poet Wislawa Szymborska would have put it, fortune embraced him as one of her darlings. The solitary night turned out to be the most important and cherished night of his entire life.

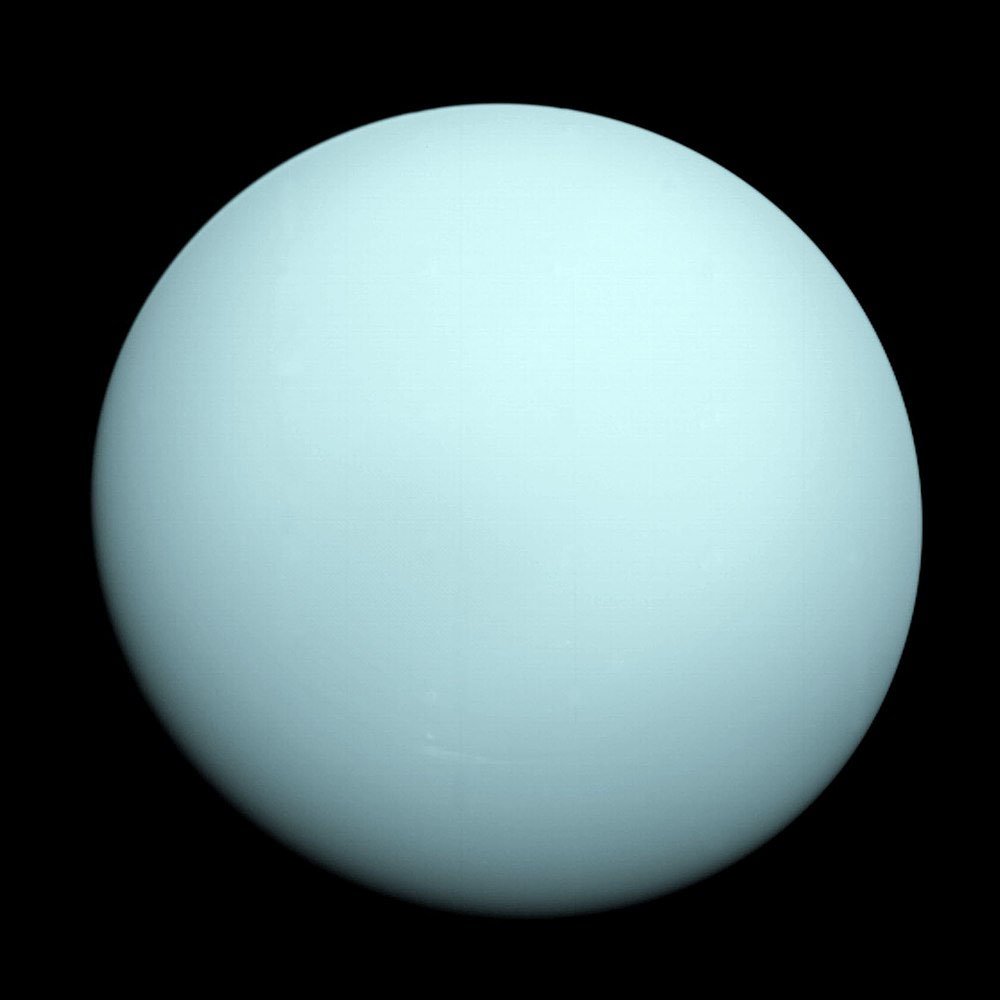

Herschel observed a shiny “disk-like” object that he had every reason to believe was a star. However, after curiously observing it for a brief period, he discovered that the “star” was orbiting the Sun. He calculated that it was orbiting 18 times farther away than the Earth orbits the Sun. What Herschel had discovered wasn’t a star, but a planet, the first to be discovered since antiquity. The discovery made him a celebrity overnight.

Herschel had discovered what we now call Uranus, but originally, he named the planet how any astronomer would do so in the day: he named it after his patron. So, for a brief period, the planets were recited as Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and… ‘Georgium Sidus’ (the Georgian Planet), after King George III. Later, to conform to the age-old tradition of naming the planets after Roman gods, it was renamed Uranus, after the Roman god of the sky. (Source)

However, Uranus, as astronomers learned, is anomalous: not only is it tilted to an astonishing 98 degrees, making it appear as though it is “rolling” around the Sun, but its orbit is also wobbly. Rather than tracing an impeccable ellipse, it often deviates. Swaying a multibillion-ton celestial body is a Herculean task, and the only force that can achieve such a feat is gravity. This is why Newton has been deemed a demigod. When he postulated his theory of gravity, he usurped the role of God: his equation, no longer than a single inch, allowed him to predict the motion of what were then called heavenly bodies.

Newton’s law was treated as gospel. In fact, astronomers were so sure of its veracity that, rather than questioning or rectifying it, they used it to predict the existence of a new planet beyond Uranus that was responsible for the anomaly. It wasn’t that Newton’s laws were incomplete, but rather because they had to be right, there had to be a planet, imperceptible to us, that perturbed Uranus’ orbit.

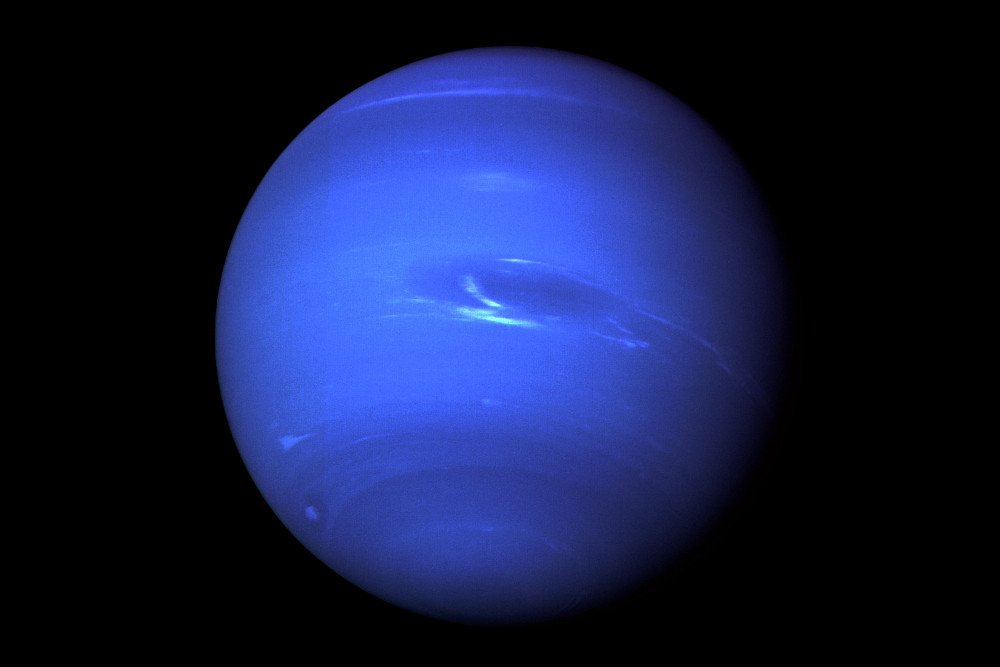

In 1846, the French mathematician and astronomer, Urbain Le Verrier, “found” another planet located some 1.6 billion desolate miles beyond Uranus. After being observed telescopically, in virtue of its dark, deep-oceanic appearance, the eighth and only planet in the Solar System to be first discovered mathematically, or as Le Verrier described it, “at the tip of my pen”, was named Neptune, after the Roman god of the sea. Yet again, what ensued was overnight success — Le Verrier became the most celebrated astronomer of the day.

Then, Le Verrier turned his proud gaze to Mercury.

Mercury’s Wobble

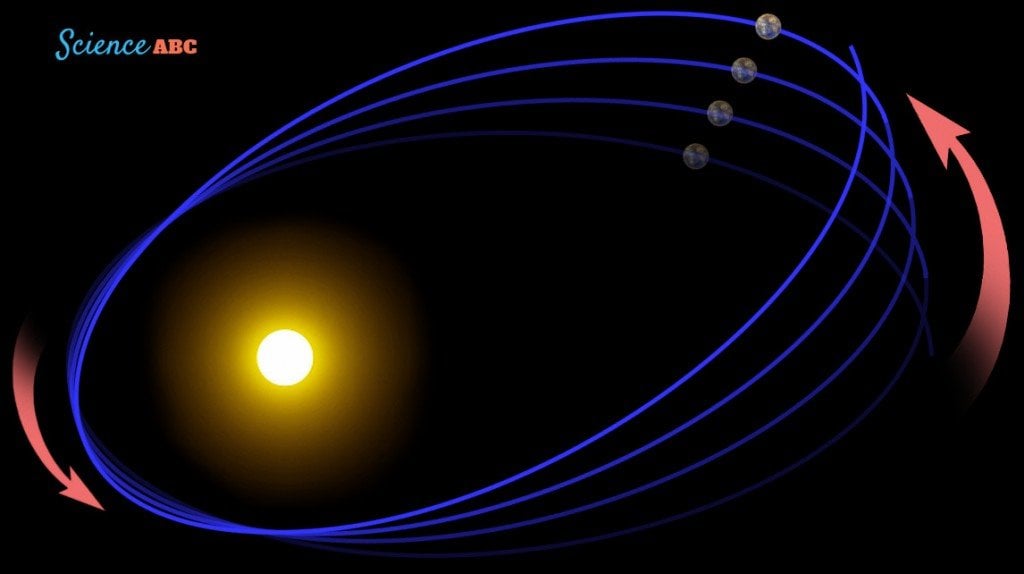

Similar to Uranus, Mercury also wobbled while orbiting the Sun. The Solar System’s closest or innermost planet doesn’t trace the same ellipse during each orbit either; it suffers what is called anomalous precession. It is also called the precession of the perihelion of Mercury, as its perihelion, its ellipse’s closest point to the Sun, sidles or drifts forward each orbit.

What was responsible for this anomaly? Le Verrier, of course, following his glorious discovery of Neptune, unhesitatingly suggested the existence of another planet between Mercury and the Sun, which he named, since it was situated so near to the searing Sun, Vulcan, after the Roman god of fire. And why wouldn’t it be true? Vulcan had to exist because Newton’s law had to be right.

So, Le Verrier and the rest of the astronomers around the world, believing the proposal in view of Neptune’s discovery, then spent the majority of their time seeking Vulcan. This was a daunting task, as a planet so close to the Sun would obviously be outshined by the Sun’s blinding light. The only way to catch a glimpse of a planet so close to the Sun would be to observe it during a transit — when it drifts across the face of the Sun as a dark, tiny dot. However, looking directly at the Sun could injure the lenses of both the observer’s eye and the telescope. Yet, surprisingly or unsurprisingly, Vulcan was discovered, not by the doyen Le Verrier, but instead by a novice named Edmond Lescarbault.

Edmond Lescarbault was a physician whose unbridled passion for astronomy forced him to pursue it as a hobby. One day in the year 1859, while surveying the sky, he observed a dot on the Sun’s disk. Edmond was dubious, as it was equally likely to be a sunspot. However, and it is rumored that just then a patient visited the physician. After Edmond attended to him, he returned to the telescope, only to witness that the dot had moved. He is reported to have watched the entire transit as it traversed the white disk, only to ultimately fall and vanish into the blue sky.

While it was also equally likely to be Mercury, he was certain that it was not, for he had observed Mercury’s transit in 1845. Had Edmond discovered a new planet? Had he just stumbled into the much withdrawn and elusive Vulcan? Le Verrier thought so. Le Verrier visited Edmond as soon as he received his letter; in fact, he was so thrilled that he arrived unannounced.

Based on Lascarbault’s data, Vulcan orbited the Sun with a period of 19 days and 17 hours. Of course, its orbit was naturally elliptic, but with an eccentricity of just 12 degrees; it was nearly a perfect circle with a radius of 21 km.

After rigorously examining Edmond’s data, Le Verrier, in 1860, officially announced to the world the discovery of Vulcan, the planet between Mercury and the Sun. For his contribution, Edmond was awarded Legion d’honneur, the highest order of merit a Frenchman can receive for military and civil merits. Le Verrier couldn’t have been prouder of himself and more in awe of Newton. However, it seemed that Le Verrier had celebrated too early – Vulcan’s existence wasn’t as conspicuous as Neptune’s.

In the following years, Le Verrier was barraged with numerous reports, mostly from unreliable sources, insisting that they had witnessed another transit. The sources were convinced that an intra-Mercurial planet had been discovered. Numerous dark spots were observed. He then incorporated their data into the original data and forecasted future transits, and when they failed to occur, he immediately tinkered with the parameters a bit more. More dots, more sightings and more data were received, but each claim was lacking substantial evidence. A definitive identity for Vulcan was yet to be established. Le Verrier passed away in 1877, but the quest continued with the same fervor.

Total solar eclipses represent the perfect opportunity to witness a dot crossing the Sun’s glaring ring that adorns the moon. Total solar eclipses in 1883, 1887, 1889, 1900, and 1901 were observed scrupulously, but no planet was captured during those dramatic periods of darkness. At this point, Vulcan seemed chimerical and, for the community of science, to believe in illusions is to commit heresy.

Then, in 1905, what is now called science’s miracle year, Einstein published four papers that spawned what we now call modern physics and revolutionized our understanding of the Universe forever.

The General Theory Of Relativity

The four papers Einstein published in the journal Annalen der Physik turned our understanding of mass, energy, space and time completely upside down. The third paper Einstein published questioned Newton himself. This was as harsh a transgression as impiety. Perturbed by the instantaneous nature of Newton’s gravity, which he surmised was a physical impossibility, he rewrote the laws of gravity. He called his theory the General Theory of Relativity.

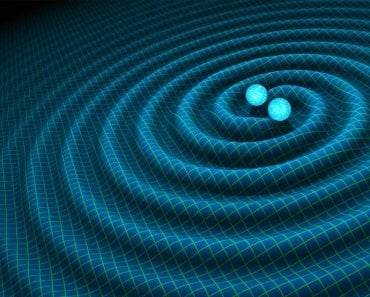

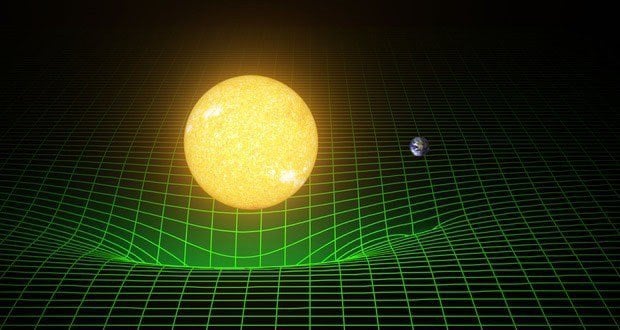

According to Einstein, spacetime formed a supple continuum, a sort of fabric on which the mundane events of the Universe would unfold. Gravity, according to him, was propagated by ripples on this fabric that travel at the speed of light, which is tremendous in magnitude, but still finite. Therefore, if the Sun were to vanish this very instant, the devastating effects wouldn’t be realized instantly, but only after 8 minutes. These waves are now called gravitational waves.

Einstein postulated that massive bodies don’t lure smaller bodies with an inexplicable tug, but instead make a slump in the fabric of spacetime in which smaller bodies helplessly fall. The Earth and its neighbors are held by the Sun — which accounts for 99% of the mass of the solar system — as they ceaselessly slide into the enormous slump it has made. Perhaps even Vulcan?

In response to his papers, Einstein’s tobacco-fueled sanity was questioned, and the reason why barely comes as a surprise. Not only was he challenging a theory that had stood the test of 400 years of time, but in his bizarre, almost psychedelic universe, space and time were not definite, but could be stretched and shriveled in the presence of mass or energy, which, by the way, he also proved were one and the same thing. In Einstein’s universe, one of man’s most perennial and deepest desires were finally capable of being fulfilled: time travel.

Mercury’s wobble was Newton’s only failing. However, when Einstein, to test his theory for the first time, fed its orbit’s data into his equations, what they expelled were numbers that exactly matched observations. Einstein felt euphoric and tremulous at the same time. In fact, the award-winning science writer and documentarist Tom Levenson, the author of The Hunt for Vulcan…And How Albert Einstein Destroyed a Planet, Discovered Relativity, and Deciphered the Universe, claimed that Einstein literally suffered heart palpitations as a result of what he had just witnessed.

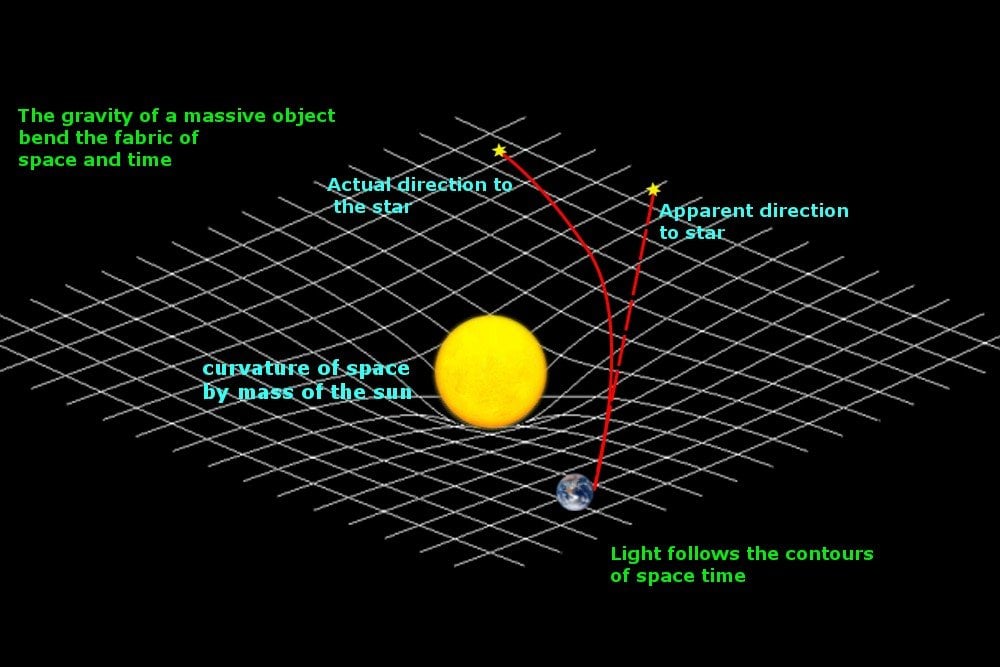

It took 14 years and another total solar eclipse until Einstein’s theory was confirmed. In fact, between 1905 and 1919, another total solar eclipse was patiently observed in 1908, but not to confirm Einstein’s theory. It was another attempt to seek Vulcan, which failed miserably, yet again. However, the prolonged 60-year search and Einstein’s misery was finally put to rest once and for all by Sir Arthur Eddington after he observed the total solar eclipse in May of 1919.

Einstein’s theory predicted that the slump in spacetime made by massive bodies such as stars is so immense that even light, rather than darting straight ahead, is forced to bend around the bulge. Understand that light cannot be pulled gravitationally, as it’s massless; instead, the light “bends” because the space around the Sun, the path it takes itself is curved. This is exactly what Eddington’s photographic plates limned: light received from stars situated behind the Sun, while traveling towards us, had to bend around the Sun’s bulge.

Einstein was right. His bizarre, psychedelic perspective was the right way to view the Universe. The proper noun “Einstein” promptly became an abstract noun, a synonym for genius, of the highest order, of course. Although Einstein’s victory didn’t mean Newton’s defeat, it wasn’t a zero-sum game. Newton’s theory wasn’t to be discarded entirely, as it was still accurate and much simpler for smaller masses and distances. The Apollo missions were solely based on Newton’s theory, not Einstein’s. This is profoundly remarkable for a theory devised 400 years ago, and those missions stand as a testament to Newton’s divine intellect.

Einstein was right. His bizarre, psychedelic perspective was the right way to view the Universe. The proper noun “Einstein” promptly became an abstract noun, a synonym for genius, of the highest order, of course. Although Einstein’s victory didn’t mean Newton’s defeat, it wasn’t a zero-sum game. Newton’s theory wasn’t to be discarded entirely, as it was still accurate and much simpler for smaller masses and distances. The Apollo missions were solely based on Newton’s theory, not Einstein’s. This is profoundly remarkable for a theory devised 400 years ago, and those missions stand as a testament to Newton’s divine intellect.

According to General Relativity, Mercury’s deviations are actually the planet taking the shortest path it can through the spacetime distorted by the Sun. The theory’s elegant explanation of the planet’s wobbles had no room for Vulcan. As soon as the theory was confirmed, Tom Levenson writes, “Vulcan became not only non-existent but unnecessary.”

“The Planet That Wasn’t There”

What then were the mysterious spots that Edmond and a plethora of astronomers had observed for half a century? Henry Courten, who studied the photographic plates of the eclipse in 1970, claimed to detect several objects that seemed to be in orbit around the Sun. He narrowed the tally to seven and surmised that a small asteroid belt existed between the Sun and Mercury. The asteroids were eponymously called Vulcanoids. To date, no such claims have been substantiated, and no comets or asteroids have been found. Had Edmond observed merely sunspots? Was Courten in denial?

Dogma and science are utterly incompatible. A single shred of evidence is enough to disprove any seemingly indisputable theory, including those stemming from the God-like intelligence of Newton or Einstein. A theory regarding entropy proposed by our generation’s most venerated physicist, Stephen Hawking, proved to be fallacious, which he remarked was not a bit embarrassing or humiliating, for that is the essence of science — scientists challenge their views every single day and are prepared to abandon even their most cherished beliefs if the evidence doesn’t follow, regardless of how disconcerting it may be.

Human beings carry millennia-old evolutionary baggage that has rendered us fraught with irrational biases. For its self-deceptive nature, Tom Levenson reviews Vulcan’s story as a “cautionary tale”. He believes that it makes us realize “how hard it is to understand what nature is telling us, how hard it is to understand when nature says no.” He reasons that “people kept discovering Vulcan because the way they saw the world required Vulcan to be there.”