Table of Contents (click to expand)

There are different types of missiles, some of which require physical contact with the target in order to detonate, while others are designed to detonate as soon as they come close enough to the target. The latter type of missile, which uses a proximity fuse, will detonate automatically when the distance between the missile and the target becomes less than a predetermined value. This allows for more damage to be inflicted over a larger area without actually hitting anything.

A few days ago, I was watching a documentary about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The documentary dealt specifically with the design of the atomic bombs and how their transportation over hundreds of miles and eventual delivery were considered two incredibly big challenges.

It was in the documentary that I first came to know that the bomb detonated in Hiroshima actually exploded before making physical contact with the ground. In other words, it exploded a few meters above the ground. Initially, I was quite surprised when I learned this, because I had always believed that rockets and missiles have to hit their target in order to explode. However, as it turns out, that’s not true, at least not in every case.

If you don’t know already, then let me tell you… there are missiles that detonate before actually ‘touching’ their target.

So, how does that work? How do missiles manage to detonate without having to make physical contact with the target?

Recommended Video for you:

Different Requirements, Different Missiles, Different Fuses

Missiles, as you may already know, come in different shapes and sizes, and every one of them is suited for specific purposes. For example, if you want to bomb a very specific geographical location, the missile to use would be different from the one you’d use to shoot down an enemy aircraft.

As you can imagine, many factors are taken into account while designing a missile, and “what kind of target is the missile going to be used against?” is one of the most crucial things that missile makers need to answer.

As such, some missiles are designed in a way that they have to actually hit their target, or, in other words, make physical contact with the target, while others are designed to detonate as soon as they come close enough to their intended target.

Fuse Types

A fuse (also spelled ‘fuze’) is the part of a missile that kickstarts the series of events that ultimately lead to the detonation of the warhead in the missile.

Based on their mechanism of activation, fuses can be broadly classified into a few categories, including impact fuse, proximity fuse, time fuse, barometric fuse, combination fuse etc. In this article, we are going to discuss the first two.

Impact Fuse

The missiles that have impact fuses (also known as ‘contact fuses’) have to physically strike the target in order to detonate. If they fail to hit the target, then they explode whenever/wherever they strike a solid surface. These types of missile are generally used to destroy bunkers and armored tanks, because they concentrate an extremely powerful ‘punch’ in a smaller area.

Proximity Fuse

A missile with a proximity fuse will detonate automatically when the missile gets ‘close enough’ to the target, or more specifically, when the distance between the missile and the target becomes less than a predetermined value.

Proximity fuses have become the norm in almost all modern surface-to-air and air-to-air missiles. While missiles with impact fuses have their advantages (and are very effective against particularly ‘hard’ surfaces), they are not as effectual when it comes to inflicting more damage over a larger area or when hitting targets that are constantly moving.

Missiles with proximity fuses are generally used against aircraft, missiles, ships or personnel.

Why Do Some Missile Detonate Before Actually Hitting The Target?

The missiles with proximity fuses generally detonate when they come within a certain distance of their target. There are a few reasons why they detonate before hitting the target: one, an ‘air burst’ renders more damage over a larger area without actually hitting anything.

You see, an explosion usually inflicts damage in two major ways: fragmentation and shock waves. When a bomb explodes, pieces of shrapnel are ejected in every direction, which could be fatal, both for structures and personnel (fragmentation).

Also, powerful explosions (the likes of which are caused by missiles) are followed by shockwaves. These shockwaves are strong enough to not only knock people off their feet, but also rupture their eardrums, or in the worst case, cause death. One of the things that make shockwaves so lethal is that their area of impact is much greater than the shrapnel.

A World War 2 veteran who took part in the D-Day assault on Omaha beach in 1944 survived after a grenade exploded a few feet away from him. He later said in an interview that while he was not hit by the shrapnel of the grenade, he was flung into the air by an ‘invisible wave’, which felt as though he had been “hit in the head with a baseball bat”.

Shockwaves are quite powerful, and if they are produced following a particularly powerful explosion (like that of the atomic bomb of Hiroshima), they can wreak havoc and marginally increase the ‘impact radius’ of the bomb.

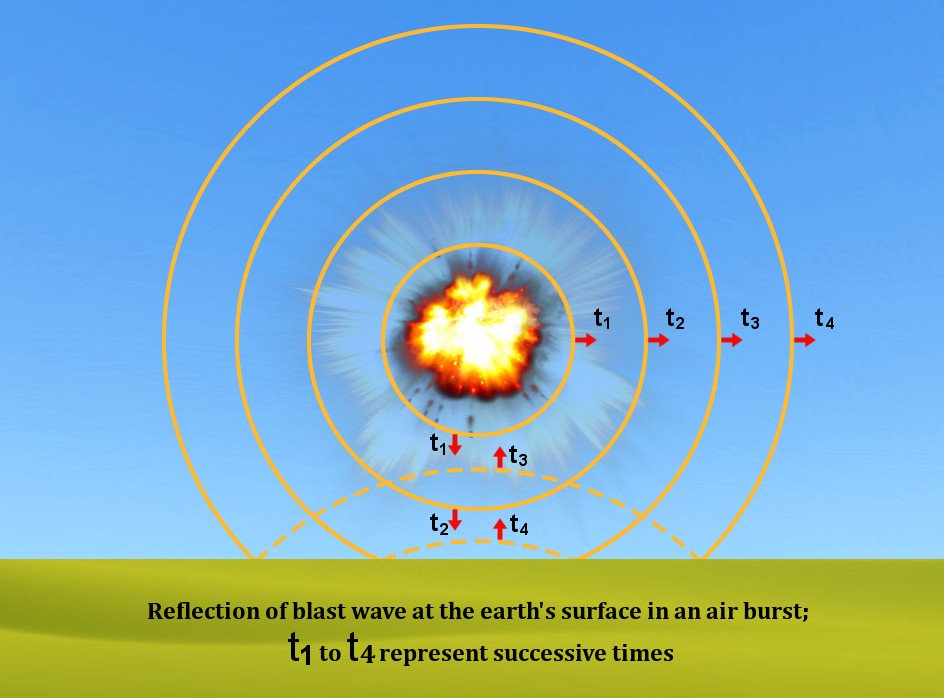

For an air burst bomb, shockwaves first travel toward the ground, and are subsequently reflected off the ground, meeting with even more shockwaves. The meeting of the original shockwaves and these ‘ground-reflected’ shock waves causes both these waves to push outwards and run parallel to the ground. This leads to an exponential increase in the lethality of the explosion.

That’s why many missiles (just like the Hiroshima bomb) explode before physically striking their target.

References (click to expand)

- (2009) Fuze, Proximity, Cutaway | National Air and Space Museum. National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution

- Lide, D. R. (Ed.). (2018, February 6). Radio Proximity Fuzes. (D. R. Lide, Ed.), A Century of Excellence in MEASUREMENTS, STANDARDS, and TECHNOLOGY. CRC Press.

- (PDF) Electronic Time Fuze Design | Dr Virendra Kumar Verma. Academia.edu

- Technical Digest Home - www.jhuapl.edu

- Fuze, Proximity, Cutaway | Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian Institution