Table of Contents (click to expand)

Our ability to socialize is limited by our available brain resources. There is an upper limit to human social groups, determined by the Dunbar number, which is 150.

You might have often stared at the huge number of friends on your Facebook or followers on Instagram/Twitter and wondered… Are these people really my ‘friends’? Are all these people relevant to my life?

Most often, the answer would be “no”. There are some connections online that fall even short of an acquaintance. There are people we randomly met on a trip or a holiday and never talked to again, some are friends of friends who we know only by name. We keep adding people to our virtual social network until it becomes a huge number, but rarely does this number translate to tangible, meaningful social relationships. We find ourselves thinking, “I can’t possibly be friends with all of them!”. But have you ever wondered why?

The answer lies within the evolutionary history of the human brain.

Recommended Video for you:

Primates And Social Cognition

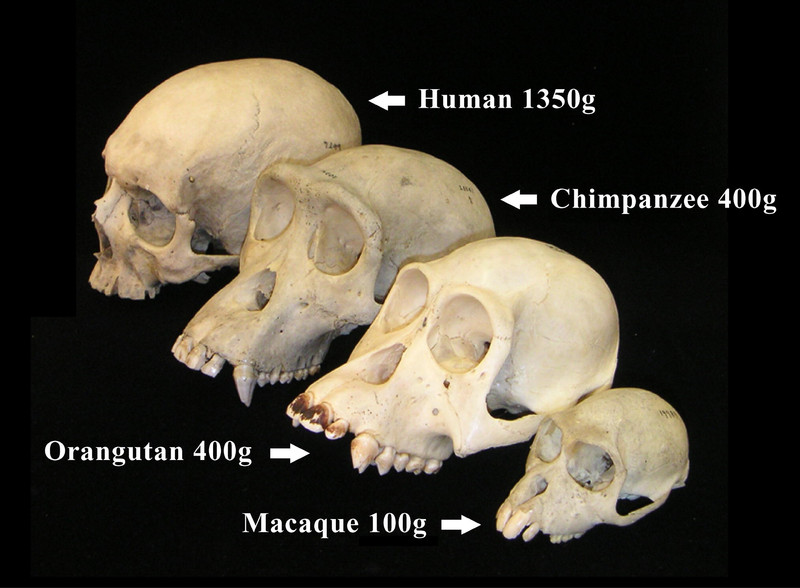

Humans are highly social beings, much like other primates, which are their “close relatives” in evolutionary terms. Primates are known for their large skulls or “cranium”, which house relatively large brains as compared to other animals.

Among primates, humans form an extreme group that evolved to have almost three times more volume in their skulls than even the closest living primates, giving us the ability to house significantly larger brains.

A British anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, suggested that primates maintain large brains that require very high levels of energy input because it serves an important purpose. Primates were largely frugivores or fruit-eating organisms. Fruits are dispersed in their supply.

This created a need to constantly maintain a mental map of their food supply, as well as information about their foraging units, or community members hunting for food. Dunbar suggested that the large size of the primate brain helped them monitor their community members across both space and time.

He tested his hypothesis by checking the correlation between the volume of the neocortex, the largest part of the brain, in 38 different genera of primates, and group size amongst other measures, such as range of the foraging area, number of days in the journey for foraging and percentage of fruit in the diet.

The study yielded some very interesting findings. He found a strong correlation between the ratio of the neocortex volume with respect to the rest of the brain and group or community size in all the primates tested.

These findings meant that primates with a significantly larger neocortex, as compared to the rest of the brain, could afford to have larger groups. They could spend more time grooming each other, and the larger brains helped them keep track of all members.

In other words, the size of our neocortex determines group size in primates. If a primate required a larger group size, they evolved to acquire more volume in their neocortex, which was required to process the high information load about the community across space and time. Primates with larger brain sizes were also found to be able to devote more grooming time with community members. Thus, maintaining friends was found to be a cognitively costly affair!

Dunbar’s Number

Based on his findings on how neocortex size constrains group size in primates, Dr. Dunbar performed some calculations to predict group size in humans based on available data on the mean neocortex volume ratio to the rest of the brain. These calculations yielded the number 150, now called Dunbar’s number. This meant that humans have the cognitive capacity to maintain a group size averaging at 150.

A later study by his group examined social network size in humans by studying the exchange of Christmas cards among individuals. At the time of the study, the internet did not exist, and Christmas cards were a common method of social networking with friends and family.

Interestingly, the maximum network size for each individual in this study was found to be close to 150! This confirmed his earlier findings on how human group size is also predicted by neocortex size, much like other primates. This theory is now known as the “social brain hypothesis”.

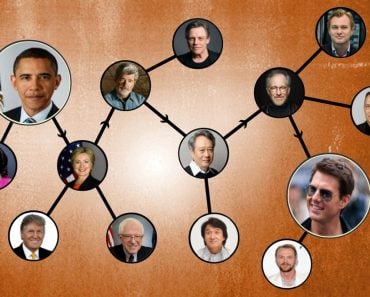

Further studies revealed a precise hierarchical structure within human groups. Human groups were ruled by a factor of three. If you have 150 people you know, 50 of them would form a close group, and 15 of them would form an even more tight-knit group of friends, followed by 5 people with whom you share the closest bond. Thus, Dunbar’s number explains not the quantity or number of friends you can have, but rather the quality or number of ‘meaningful’ social connections.

Some criticisms of this work emerged over time, claiming that human relationships are not as simple as those in primates and are governed by cultural factors, not biological ones. However, such claims lacked any substantial evidence and remain at the level of hypothesis.

The Virtual Social Network

One would think that the internet would have helped us easily jump over primitive hurdles, such as limited neocortex size while socializing. Surely, using Facebook or Instagram makes it easy to maintain real relationships as compared to ancient times.

We would all agree that tagging one acquaintance in a group picture or posting a birthday wish for them online is a much simpler task than mailing a letter, let alone personally grooming and bonding with each of our connections like in ancient hunter-gatherer societies. Funnily enough, this is not the case. Our virtual social networking was also found to be ruled by Dunbar’s number!

A study of user behavior on Twitter showed that over six months, users could stably maintain an average of only 150 relationships! Maintaining stable connections online also required the interactions and attention of an individual, which is a limited resource.

Similarly, a study on students using Facebook revealed that although they had an average of about 300 Facebook connections, most only considered roughly 75 of them as actual friends!

Whether virtual or real, social networking seems to be ruled by Dunbar’s number!

A Final Word

Humans are highly evolved primates. We may have introduced new technologies, such as the internet, which makes our life easy, but the truth remains that we are just “Primates with the internet” and are no different from other primates when it comes to social behavior.

Online or offline, our ability to socialize is limited by brain resources that we can afford to allocate for this particular function. The upper limit to our social groups remains at the Dunbar number, 150.

There is simply a limitation to how much of our brain’s resources can be devoted to socializing. There is no cheat sheet to making more friends—even with the internet to help!

References (click to expand)

- . (2002). An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy. []. Elsevier.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992, June). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution. Elsevier BV.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993, December). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Cambridge University Press (CUP).

- Hill, R. A., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2003, March). Social network size in humans. Human Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Zhou, W.-X., Sornette, D., Hill, R. A., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2005, February 17). Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- (2011) Dunbar's Number: Group Size and Brain Physiology - JSTOR. JSTOR

- Gonçalves, B., Perra, N., & Vespignani, A. (2011, August 3). Modeling Users' Activity on Twitter Networks: Validation of Dunbar's Number. (M. Perc, Ed.), PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS).

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2011, January 27). Connection strategies: Social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media & Society. SAGE Publications.