Table of Contents (click to expand)

The internet has decreased our ability to sustain attention while focused on a task. It has also made us less likely to remember facts.

If you can’t remember the last time you memorized the birthdays of your friends, you’re not alone. You are simply one of the billions of typical Internet users across the world!

Thanks to the internet, you don’t have to memorize important dates, facts, or even the lines of your favorite song anymore. Why do it, when you can so easily look it up?

But is that all it’s doing? Or does the Internet change your brain and behavior in more ways than you have ever considered?

Let’s find out!

Recommended Video for you:

Why Should We Care About The Impact Of The Internet?

The answer to that is simple. The human brain is a remarkable organ capable of a property called “neuroplasticity”. This gives the brain the ability to constantly change and adapt itself based on external input.

When you constantly do something, the brain changes in response to this action, and strengthens connections between brain cells that will help you perform this action.

Considering that we use the Internet every day for hours on end, scientists believe that this behavior will have changed the brain and its connections in various ways.

In other words, the “plastic” brain will have changed itself to mold you into a “Netizen”. However, if we don’t know what these changes are, we can’t rightly say if they are “bad” or “good” adaptations.

Another reason for the interest of scientists in this area is because the Internet is an example of a supernormal stimulus, a stimulus that gives rise to larger responses than other natural stimuli.

The internet is an example of a supernormal stimulus. A supernormal stimulus is any stimulus that appeals more to the brain than naturally occurring stimuli. For example, remembering the route to a place is a natural situation that requires the use of memory, just like remembering a folder or a webpage on the Internet. However, the latter is artificial and compared to remembering the route, brain responses to remembering stuff on the internet will be larger, or in other words “supernormal”.

Such stimuli hijack our brains and give rise to more magnified brain responses than other stimuli.

Given this, scientists are interested in understanding how the human brain has adapted to meet the demands of the internet.

Let’s look at a couple findings on how the internet has changed our brains and behavior.

Changes In Attention Span

Heavy use of the Internet requires you to constantly monitor incoming streams of information, and switch between multiple streams.

Imagine this: As you’re watching a video on Youtube, you get a notification from Instagram. While you are checking who liked your picture there, you get a message on your chatting app and you switch again! The switching process is never-ending while using the Internet.

One pioneering study showed that this type of constant monitoring and switching between incoming streams of information affects our “cognitive control,” or the manner in which our brain allocates attention.

They found that people who heavily multi-task using media were less able to filter out distracting stimuli or information while performing a given task.

Furthermore, while performing one task (let’s call it Task 1), their brains are constantly alert and ready to “switch on” the brain regions required for the next task (Task 2). This makes them easily distracted by information relevant to Task 2 while they’re performing Task 1.

These findings showed that the constant multi-tasking due to Internet use teaches our brains that anything that “pops up” while working on a task may not actually be a distractor, but might be useful information.

Eventually, this makes Internet users unable to stay focused on one task, because they’re unable to filter out distracting, irrelevant information.

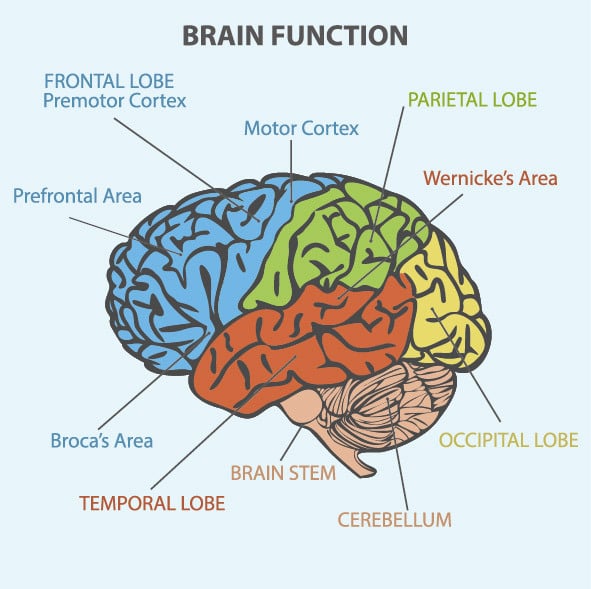

Neuroscientists have found that adolescents and young adults who report themselves to be heavy media users show worse performance on simple speech listening and reading tasks and exhibit higher activity in their right prefrontal cortex which handles attentional control.

Those users required greater effort, using their prefrontal cortex, to sustain their attention on a given task and filter out “distractors,” notably more than light media users.

Therefore, it is safe to say that the Internet does, in fact, change our brains!

Effect On Memory

If you’re asked “What is the exact speed of light?”, what would you do? Most likely, you would “google it”.

This is so common and pervasive in our daily lives that we have invented a new verb for it.

But how does this impact our brains?

Our brains store information or facts about objects, people and concepts, etc. using their “semantic memory”. All the information we have acquired over years about the world is stored as semantic memory in the left temporal and parietal brain regions.

The use of the internet has made the use of semantic memory in our daily lives slightly non-essential.

In a study aimed to understand how constant “googling” has changed our brain and behavior, participants were given trivia statements and the digital location where this information would be saved. When tested on memory tasks, the participants were less likely to remember “what” the statements themselves were, but remembered “where” to look for them on the computer.

The scientists called it “the Google effect”, and they argue that our expectation of information being constantly available via the internet has changed the way the human brain encodes information. It is a medium for “transactive” memory, where we can “offload” our semantic memory.

Interestingly, one study found that more analytical people (those who do better on reasoning) are less likely to resort to such “offloading” using their smartphones than more intuitive people. So, not everyone resorts to this process equally.

The constant “internet search behavior” can modify brain anatomy by changing the white matter (the long tails of nerve cells) connections in the superior longitudinal fasciculus of the brain.

The good news is that this type of “offloading” does have some positive effects. Through an interesting experiment, scientists found that digitally “saving” information in a file improved the memory of participants on other, newer information.

On the other hand, this improvement in memory was not seen in cases where the “digital” saving process was unreliable and forced them to remember the older information.

Thus, digital off-loading of information enables our brain to be more economical in spending its resources. It frees the brain from the responsibility of memory so that it can engage in more productive tasks. Not a bad tradeoff!

The Impact On Social Life

The internet has moved our social relationships online. Although the Internet makes socializing easier and global, it does not considerably increase the size of our social network.

This is because online social relationships, similar to the real world, are limited by the availability of the same amount of brain resources (Read more here). In other words, you can’t magically “grow” more friends online than you do offline!

A Final Word

The internet, due to its supernormal nature, has modified our brain and behavior in several ways. It has decreased our ability to sustain attention and avoid becoming distracted easily while on a task. While it has technically reduced our memory “load”, making us less likely to remember facts, this has also freed the brain up to engage in more useful activities.

The online social life, although more global than our real-world social network, continues largely unchanged and is governed by the same limitations as our offline social life.

The Internet has undeniably changed the human brain and behavior, but it’s hard to say that all the changes are “bad”. However, it is useful to be mindful of these effects and keep caution in mind when using the Internet.

References (click to expand)

- Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. D. (2009, September 15). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Moisala, M., Salmela, V., Hietajärvi, L., Salo, E., Carlson, S., Salonen, O., … Alho, K. (2016, July). Media multitasking is associated with distractibility and increased prefrontal activity in adolescents and young adults. NeuroImage. Elsevier BV.

- (2014) Semantic memory. - APA PsycNet. The American Psychological Association

- Binder, J. R., & Desai, R. H. (2011, November). The neurobiology of semantic memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Elsevier BV.

- Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015, July). The brain in your pocket: Evidence that Smartphones are used to supplant thinking. Computers in Human Behavior. Elsevier BV.

- Dong, G., Li, H., & Potenza, M. N. (2017, June 29). Short-Term Internet-Search Training Is Associated with Increased Fractional Anisotropy in the Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus in the Parietal Lobe. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Frontiers Media SA.

- Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011, August 5). Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Storm, B. C., & Stone, S. M. (2014, December 9). Saving-Enhanced Memory. Psychological Science. SAGE Publications.