Table of Contents (click to expand)

Curling has generated a lot of attention since the 2014 Winter Olympics, but fans of the sport might be surprised by the complex physics at play in this unusual sport.

Every four years, around the time of the Winter Olympics, there is a surge in interest (and consequently memes) about curling. From players wearing two different types of shoes on each foot, to the use of brooms, to excessive yelling directed at an inanimate stone… curling has managed to carve out a niche audience.

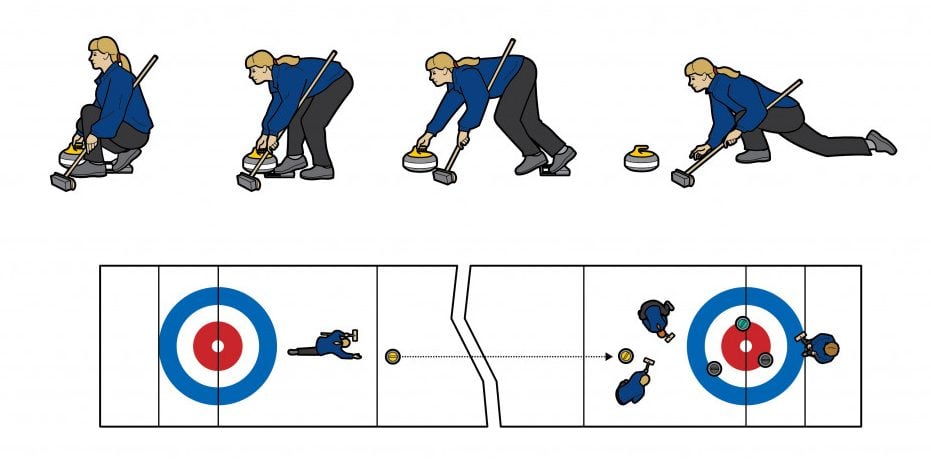

To those who don’t know, curling is a team sport in which a player hurls a piece of stone towards a target circle over a sheet of ice. The player’s team members vigorously sweep the floor using brooms to influence the speed and path of the stone. The player who throws the stone gives it a slight twist, causing it to curl along the way, hence the name of this winter sport.

Seems simple, right?

Compared to other sports, curling may seem quite straightforward, but there is much more to it than meets the eye. In fact, scientists around the world argue over the exact physics of the sport.

The question that puzzles experts, scientists and players alike is: “Why does a curling stone curl the way it does?”

Recommended Video for you:

History Of Curling

Curling is not a sport invented by millennials or any other recent generation. In fact, its origins can be traced back to 16th-century Scotland.

Pictorial evidence that curling is a medieval sport can be found in the works of the Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel. “Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap” and “The Hunters in the Snow” depict peasants involved in an action that resembles curling over a frozen body of water, such as a pond or a river.

Interestingly, the curlers in these works of art do not have a broom, which is the most distinctive equipment used in the sport’s modern era.

The earliest recorded game of curling took place in February of 1541 between John Scalter, a monk at Paisley Abbey (a Parish church), and Gavin Hamilton, a representative of the Abbot. The game was recorded in Latin by a notary named John McQuihn. Written evidence of the sport’s origins can also be found in the works of poets from the Renfrewshire and Lanarkshire regions.

The sport’s medieval presence and geographical origins were solidified by the discovery of a curling stone dated 1511 in a pond in Dunblane, Scotland. This stone is now preserved in the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum alongside the world’s oldest football.

Fast-forward to the 18th and 19th centuries, when Scottish emigrants introduced the sport to other countries, such as Canada, the USA, and New Zealand; it gradually rose in popularity and eventually became an Olympic sport.

Rules Of Curling

Each team consists of four players. The players are called the lead, second, third, and skip (or captain) based on their role.

The team leads alternatively throw the stone towards the target circle, formally known as the house center (or button), while the second and third players sweep the ice to influence the stone’s trajectory. The team captain communicates with the sweepers and instructs them on how hard to sweep and decides the overall strategy.

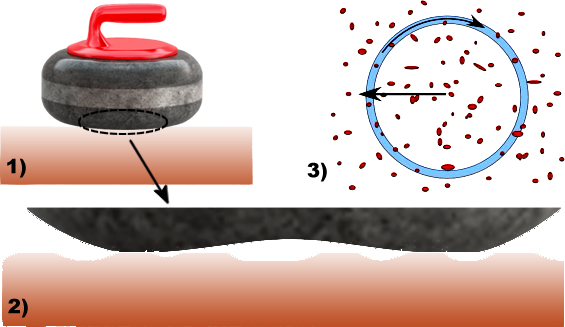

The curling stone is made of granite sourced from two specific locations. Importantly, the curling stone does not have a flat bottom, so only a tiny ring (running band) stays in contact with the ice sheet.

The sport of curling is also known as ‘The Roaring Game’ due to the sound produced by the rock traveling over the ice sheet.

Vigorously sweeping warms the ice and causes the ice to melt. The resulting water film reduces the surface friction between the running band and the ice sheet. The lower the friction, the further the curling stone will travel and vice versa. The amount of sweeping also influences how much the stone curls.

For televised games, curling has a scoring system similar to baseball. A game of curling is divided into 10 separate ends (innings) and in each end, a team throws eight stones. At the conclusion of the sixteen (eight per team) throws, the team with the stone closest to the house center is awarded a point for each stone closer to the button than the opponent team’s closest stone.

The team with the most points after the 10 ends is declared the winner.

Why Does A Curling Stone Curl?

Before we get to the question of why a curling stone curls the way it does, we have a simple activity for you to perform.

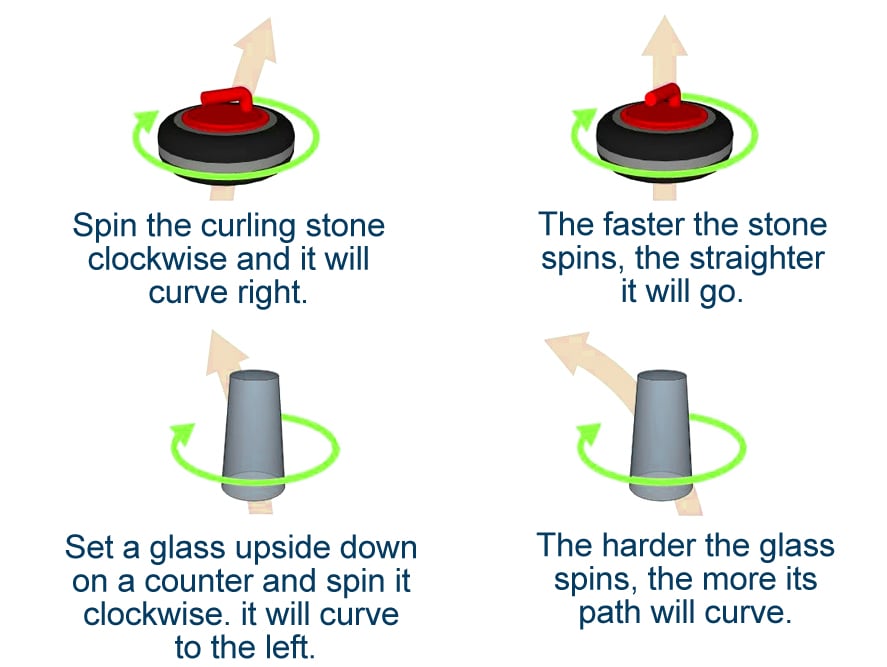

Grab any hollow, cylindrical object—say, a glass—and place it upside down on a flat surface. Then, slide it across the surface while imparting a slight spin on it. If the actions are done correctly, you will notice that the rotation of the glass and the curl are in opposite directions.

For example, if you rotate the glass clockwise, it will curl counter-clockwise (move towards the left) down the surface. However, a curling stone does not reflect the same behavior. Curling stones curl in the same direction as the initial rotation (spin).

There are three different theories explaining the strange behavior of curling stones.

The first theory suggests that the unusual curling of granite stones has more to do with the ice surface than with the stones themselves.

Unlike ice hockey and ice skating, the ice sheet in curling is not flat, but rather pebbled. Before a game, water is sprayed onto a flat sheet of ice, which results in the formation of irregular-sized pebbles. A metal blade is then used to nip the irregular pebble tops and create a uniform surface of some sort.

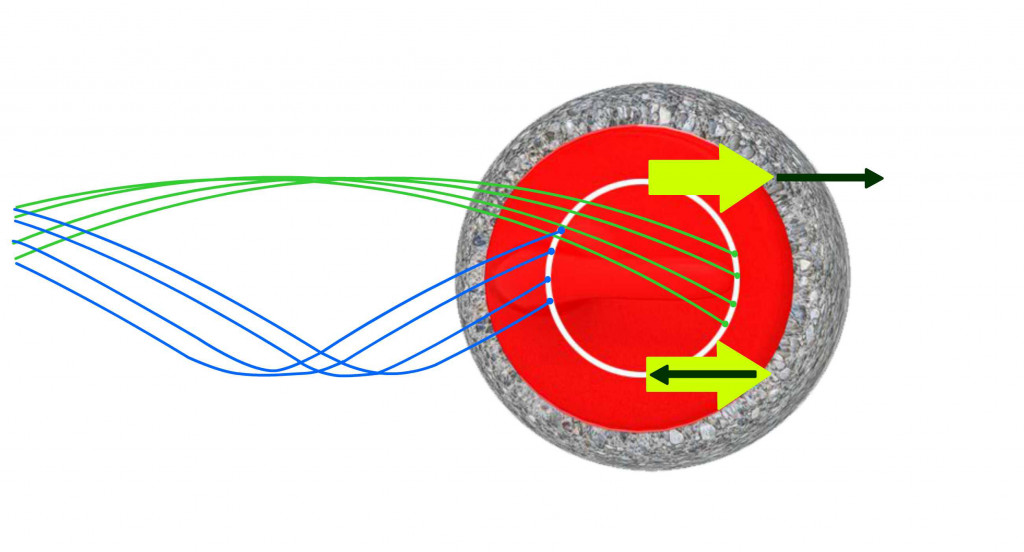

The running band of the granite stone is believed to slightly pivot in the direction of spin as it moves over a pebble. This slight pivot increases exponentially as the stone runs down the surface and presumably moves over thousands of pebbles.

According to the next theory, the irregularities present on the running band are responsible for the stone’s curling direction.

The irregularities scratch the ice surface, which in turn steer the curling stone in the direction of the induced spin. Scratching the ice surface using sandpaper and then tracing the movement of curling stones has proven this theory to some degree.

The final theory states that the non-uniform melting of the ice causes the stone to curl the way it does. As the stone travels, it presses more strongly on the front end of the running band than it does on the back end. Due to the greater forward force, the ice in front melts quicker than the ice in contact with the rear side of the running band. The melting of the ice reduces friction at the front, causing the stone to curl in the direction of induced rotation.

Conclusion

While all the above theories seem plausible and have some experimental proof to support them, research is still being carried out to find a definitive answer. This baffling phenomenon, coupled with the level of skill and strategy required in deciding which shot (guard, takeout, draw) should be executed, the amount of sweeping, predicting the curl of the stone, and ultimately winning a game of curling, have all earned this sport the nickname “Chess on Ice”!