Table of Contents (click to expand)

Sea snakes are ovoviviparous; they give birth to live young. In this type of reproduction, the embryo develops in an egg, but the mother does not lay the eggs. The mother holds the eggs in her body until the embryo develops into a fully functional offspring.

Sea snakes live their whole lives underwater, they are born underwater, and there they will die. And like all reptiles, the young develop inside eggs. However, eggs float in salt water, making them vulnerable to predators and the environment. So, what exactly do these creatures do to avoid such an unpleasant fate?

First, let’s take a look at what other marine reptiles do.

Recommended Video for you:

What Do Other Marine Reptiles Do?

Sea snakes belong to the same order as all other snakes. They evolved separately from their cousins, the sea kraits. Sea kraits are the amphibious cousins of the sea snake. That does not mean that they are amphibians, like frogs, but rather that they live on land and in water.

The distinction between the two is that sea kraits come on land to lay their eggs. This helps protect the eggs from vulnerability and gives them the warmth they need to hatch. Many animals, like sea turtles and crocodiles, do the same thing. They often bury their eggs in the sand to protect them and keep them warm.

Even sea snakes need to protect their eggs and keep them warm, but they don’t lay their eggs on land. And what do they do instead? They don’t lay eggs at all. Sea snakes give birth to live young!

Oviparous And Viviparous

What’s the big deal in birthing live wriggling sea snakes? Humans and other mammals give birth to live young too.

First, we need to understand the difference between what happens in an animal that lays eggs and an animal that gives birth to live young.

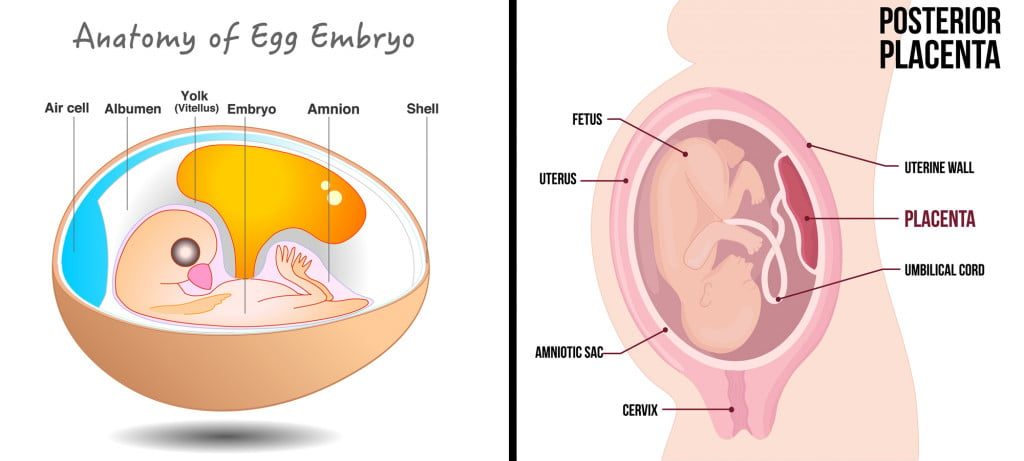

An animal that lays eggs is called oviparous, such as a chicken. These animals will lay eggs that are covered by hard shells. Within the hard shell is a developing embryo, along with a yolk sac, which acts as a food source for the baby. The embryo develops into a young one outside the body of its mother and hatches from those eggs as a fully functional animal.

We call animals that give birth to live young viviparous animals. This birthing style is mostly limited to mammals (humans, apes, donkeys), with a few exceptions (certain sharks, rays and even some fish). In this type of reproduction, a placenta connects the mother to the children. This connection is how the embryo receives nutrition. The child will form completely inside the mother before being born.

So, doesn’t that mean that sea snakes are simply viviparous? Not completely!

A Mix Of The Two

Sea snakes are ovoviviparous. That word is a mixture of oviparous (egg laying) and viviparous (live birth). In this type of reproduction, the embryo develops in an egg, but the mother does not lay the eggs. The mother holds the eggs in her body until the embryo develops into a fully functional offspring.

The reason it is a separate type of reproduction is that it has elements of both main types. There is the formation of an egg, with a yolk, and the embryo feeds on that yolk, unlike in viviparous reproduction, where the nutrition comes from the mother through a placenta.

And like oviparous reproduction, the young one emerges from an egg outside of the mother’s body. The little sea snake eggs hatch while it’s still inside the mother, who then expels the young from her body.

This adaptation is very interesting, especially when it comes to the sex determination of offspring. In reptiles, either temperature or genetics will determine the sex of the offspring. For the sea snakes to be able to reproduce at sea, they cannot have temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD). If that were the case, almost every single offspring born would be of the same sex, because it would be determined by the relatively stable body temperature of the parent.

It is important that there is a good ratio between males and females. Therefore, it is very important for sea snakes to have genotypic sex determination (GSD). GSD ensures that there are enough males and females for the species to survive. With TSD, this would not be the case. This means that sea snakes had to evolve GSD before entering the water, or else they would not have survived.

Conclusion

Just like with sex determination, there’s a lot to be learnt about ovoviviparous animals. Sea snakes are not the only ovoviviparous animals; other animals like basking sharks also display this phenomenon, and there is very little we understand about it.

Studying why some species evolved to have ovoviviparous births over returning to the land is not fully understood. It is also a lot tougher to study the developmental stages of these animals. These beautiful creatures remain very mysterious and there’s so much more we hope to learn!

References (click to expand)

- Diversity, biology and ecology of sea snakes (hydrophiidae .... journalcra.com

- Sea snakes - CEBC. cebc.cnrs.fr

- Voris, Harold. (1977). A phylogeny of the sea snakes (Hydrophiidae). Fieldiana Zoology. 70. 79-166. - ResearchGate

- Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia - CSIRO Publishing. CSIRO Publishing

- (2014) Records of sea-kraits (Serpentes: Laticaudidae: Laticauda) in .... JSTOR

- Shine, R., Shine, T., & Goiran, C. (2019, June 17). Morphology, reproduction and diet of the greater sea snake, Hydrophis major (Elapidae, Hydrophiinae). Coral Reefs. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- (2011) Preliminary observations on the reproductive biology of six .... The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Heatwole, H., Grech, A., Monahan, J. F., King, S., & Marsh, H. (2012, June 4). Thermal Biology of Sea Snakes and Sea Kraits1. Integrative and Comparative Biology. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Hickman C. P., Roberts L. S.,& Larson A. (2001). Integrated Principles of Zoology. McGraw-Hill

- WOURMS, J. P. (1981, May). Viviparity: The Maternal-Fetal Relationship in Fishes. American Zoologist. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Janzen, F. J., & Paukstis, G. L. (1991, June). Environmental Sex Determination in Reptiles: Ecology, Evolution, and Experimental Design. The Quarterly Review of Biology. University of Chicago Press.

- Cetorhinus maximus – Discover Fishes. The Florida Museum of Natural History