Table of Contents (click to expand)

Some animals can perform parthenogenesis which is the ability of an individual to produce offspring without mating. Offspring produced via parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction) are identical to their parents (also called clones).

Growing up, we probably all had that conversation about the “birds and the bees” with our parents or teachers. While much of it may not have made sense at the time, our Biology classes in school likely cleared things up.

While human reproduction is straightforward, animal births are a lot more complex (and intriguing!). Most wild animals need to mate to produce offspring, but there are a handful of species that do not mate and yet still produce new generations. This phenomenon is called ‘virgin births’ or ‘parthenogenesis’.

Recommended Video for you:

Sexual Vs Asexual Reproduction

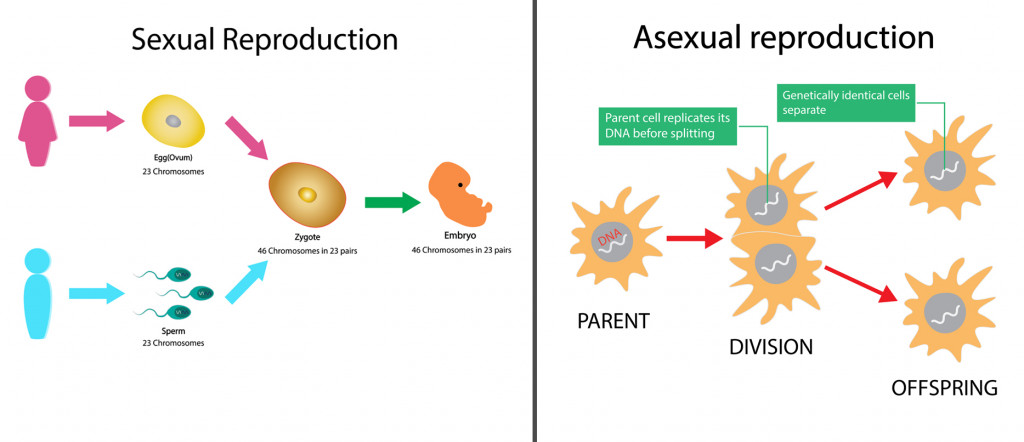

Animals reproduce either through sexual reproduction or asexual reproduction. In sexual reproduction, males and females mate to produce genetically unique offspring. Here, both the egg and sperm are necessary, as they the carry genetic information that is required to produce offspring.

Asexual reproduction, on the other hand, does not require the fusion of gametes to produce new individuals. Here, offspring are produced from a single parent’s ovum. Unlike sexual reproduction, where offspring are genetically diverse, offspring produced via asexual reproduction are identical to their parents (also called clones).

What Is Parthenogenesis?

Parthenogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction. Parthenogenetic organisms supplement genes provided by the sperm in sexual reproduction. New individuals develop from an unfertilized egg and are genetically identical to their parent.

Species that are parthenogenic may either be facultative, meaning that organisms can switch between sexual reproduction and parthenogenesis, or obligate, meaning that the organism is incapable of sexual reproduction.

Pathogenic Animals: Animals That Can Reproduce Asexually

There are over 80 known species of fish, reptiles and amphibians that reproduce parthenogenetically. These species rely on facultative parthenogenesis only under dire circumstances, including when females are isolated from males.

Here are a few examples of parthenogenetic species from different taxa.

Komodo Dragons

Let’s be honest… who would have ever thought the world’s largest lizard, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), could reproduce via parthenogenesis? But yes, it’s true! In 2006, a female Komodo dragon housed in Chester Zoo, U.K. laid a clutch of 25 eggs, even though she had never mated or been in the presence of a male dragon.

Similarly, in the London Zoo, another captive-bred female produced four eggs two-and-a-half years after her last interactions with a male dragon. This individual laid another clutch after mating with a male dragon, which revealed that the species used facultative parthenogenesis to reproduce.

Komodo dragons are only found in some parts of the world, and they are under severe threat from poaching. As a result, their populations are often skewed—with fewer males and more females (or vice versa). Here, it is likely that female dragons were forced to adopt facultative parthenogenesis due to the lack of male dragons in captivity.

Stick Insects

In 2013, a group of Australian scientists investigated the life history of spiny leaf stick insects (Extatosoma tiaratum). They found that the females resisted mating with males by using one of three approaches. They would either kick their legs and curl their abdomens, or they would alter their pheromones—the odor molecules organisms release to communicate—to appear inconspicuous to males, or they would secrete anti-aphrodisiac chemicals that repelled males.

The study concluded that female stick insects, under some circumstances, benefit by not mating. This, researchers suspect could further lead to the evolution of facultative parthenogenesis in the species.

Copperhead Snake

Several snake species can reproduce via parthenogenesis. One Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) in Indiana, USA, gave birth to a stillborn offspring and four infertile eggs. They had captured this individual from the wild and kept her in an enclosure, one she had never shared with another snake. In fact, she had not mated in nine years.

Desert Grassland Whiptail Lizards

Desert grassland whiptail lizards (Aspidoscelis uniparens), as their name suggests, are found in desert and grassland ecosystems in the United States of America.

This species is unique, as they are an all-female species. Therefore, as you might have already guessed, they can only reproduce using parthenogenesis. Desert whiptails reproduce offspring via meiosis, and because all of their chromosomes come from the mother, all the offsprings are clones and female.

This species is also known to exhibit male-like behavior in order to initiate pseudo-copulation with other females, which stimulates reproduction.

One of the major advantages of parthenogenesis in this species is that it can reproduce much faster than those species that reproduce sexually, allowing for a rapid increase in population when conditions are ideal.

Zebra Shark

A group of Australian researchers investigating captive zebra sharks (Stegostoma fasciatum) found that the species could switch from sexual reproduction to parthenogenetic reproduction in captive environments.

In 1999, the researchers introduced a female zebra shark captured from the wild to a captive male zebra shark. During this time, the two mated, after which they separated the pair. This reuniting and separating went on for a few more years until 2012, when the male was permanently separated from the female. Once the mating stopped, so did her production of eggs.

The next year, in 2013, the researchers introduced the female’s daughter into her tank. Interestingly, during this time, the mother began laying eggs again! However, an even bigger surprise came from her daughter, who had reached maturity herself and began laying her own eggs, even though she had never mated with a male!

The researchers believe that the embryos in the mother’s egg developed because the shark could store the male’s sperm for a long time, or because it was parthenogenetic. On the other hand, parthenogenesis seemed most likely for the daughter, as she had never mated.

There are a few reasons animals choose (or are forced) to reproduce without mating. To begin with, parthenogenesis eliminates the cost of sexual reproduction entirely by avoiding any investments by males or in courtship. This saves animals a lot of time and energy.

Second, it helps species like komodo dragons thrive in uninhabited islands, as a single female can create a population on her own. Finally, such processes are likely the last resort for reproduction for many reptiles, insects, and amphibians living in harsh environments, such as deserts.

However, parthenogenetic species are often termed as ‘dead-ends’, since they produce clones, which do not have any new trait combinations. Because all the offspring are clones and are incapable of adapting to changing environments, they succumb faster to disease, which can ultimately threaten or reduce their populations in drastic ways.

References (click to expand)

- Watts, P. C., Buley, K. R., Sanderson, S., Boardman, W., Ciofi, C., & Gibson, R. (2006, December). Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Burke, N. W., Crean, A. J., & Bonduriansky, R. (2015, March). The role of sexual conflict in the evolution of facultative parthenogenesis: a study on the spiny leaf stick insect. Animal Behaviour. Elsevier BV.

- Jordan, M. A., Perrine-Ripplinger, N., & Carter, E. T. (2015, March). An Independent Observation of Facultative Parthenogenesis in the Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix). Journal of Herpetology. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

- Desert grassland whiptail - Toronto Zoo | Animals. Toronto Zoo

- Dudgeon, C. L., Coulton, L., Bone, R., Ovenden, J. R., & Thomas, S. (2017, January 16). Switch from sexual to parthenogenetic reproduction in a zebra shark. Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.