Compact discs (CDs) store data in the form of tiny indentations on a smooth surface. A CD player uses a laser beam to read these indentations and convert them into digital data. However, scratches on the surface of the CD can cause the laser beam to scatter, making it difficult for the CD player to read the data correctly.

A few years ago, when USB sticks and cloud computing were not as popular as they are today, data was primarily stored and retrieved with the help of CDs. Today, shiny circular discs are known for storing data ranging from a few hundred megabytes to a few gigabytes.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Compact Disc?

Compact disc CD is a digital storage format for optical media jointly developed by Philips and Sony. The CD format was originally developed for storing and playing sound recordings but was later adapted for storing data.

Data on a CD is encoded with the help of a laser beam that etches tiny indentations (or bumps, if you will) on its surface. A bump, in CD terminology, is known as a pit and represents the number 0. Similarly, the lack of a bump (known as land) represents the number 1.

However, one of the biggest challenges with CDs is their delicate, smooth surface, easily scratched if not treated with the utmost care. Cracks and scratches on the surface of a disc impede its ability to store data and make it difficult for a CD player to retrieve the data stored in it.

But why exactly does this happen? Why are scratched CDs harder to read / access?

Before we come to that, we first have to understand how a CD works.

How Does A CD Work?

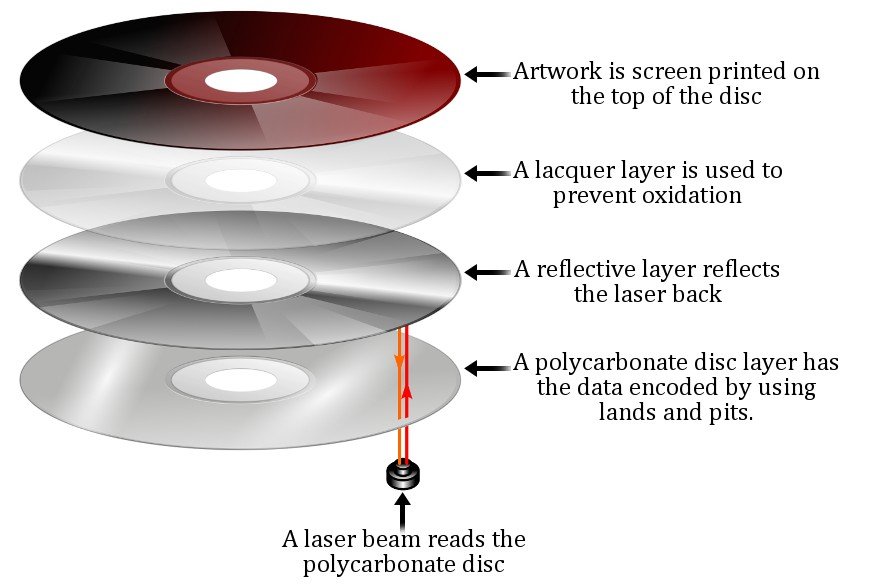

A CD is usually around 12 centimeters (4.5 inches) in diameter and consists of a couple of thin circular layers attached one on top of another.

Most of a CD is composed of a plastic called polycarbonate. The bottom layer is a polycarbonate layer where data is encoded by using tiny bumps on the surface. Above this layer is a reflective layer typically made of aluminum (gold is also used, although quite rarely).

Above the reflective layer is a protective layer of lacquer and plastic, which shields the layers below. The artwork or label is printed on the lacquer layer (i.e., on top of the CD) via offset printing or screen printing.

CDs store information digitally, i.e., with the help of millions of 1s and 0s. Data on a CD is encoded with the help of a laser beam that etches tiny indentations (or bumps, if you will) on its surface. A bump, in CD terminology, is known as a pit and represents the number 0. Similarly, the lack of a bump (known as land) represents the number 1. Hence, a laser beam can encode the required data into a compact disc using pits and lands (0 and 1, respectively).

Now that you know how a CD is encoded with data let’s look at how a CD player actually reads this stored data.

How Does A CD Player Work?

There are two main components in a CD player that help read a CD: a tiny laser beam known as a semiconductor diode laser and an electronic light detector, basically a tiny photoelectric cell. When you turn on the CD player, an electric motor in the player rotates the CD at a very high speed while reading the outer edge at 200 RPM, and when reading the inner edge, it rotates at 500 rpm.

The laser beam source inside the player switches on and scans along a track from the center of the disc to the outer rim. It focuses a 780 nm wavelength (near-infrared) beam through the underside of the compact disc. When the beam falls on land (1), it reflects straight back, but it scatters when the beam falls on a pit (0).

When the photocell detects the reflected light, it recognizes that the laser must have hit land and, in turn, sends a signal to a circuit that generates the number 1. Likewise, when it does not detect light, it correctly determines a pit at this point so that the circuit generates the number 0. Thus, the photocell uses the intensity changes of the reflected beam to determine whether there is a 1 or a 0 on the disk.

Why Is It Difficult For A CD Player To Read The Contents Of A Scratched CD?

The data from a CD / DVD / Blu-ray disc is not on the glossy surface but the polycarbonate layer at the bottom of the disc. As already mentioned, a CD player has a laser beam that reflects/scatters from the underside depending on whether it falls on a land/pit. Indentations on the surface of a disc are very, very small, so scratches and cracks mess up the way light bounces off the surface of the CD.

When the laser falls on a scratched spot, it scatters, even if there is no bump at this point. As a result, the photocell transmits incorrect information to the circuit, making it difficult for the CD player to read the data correctly.

However, scratches do not necessarily make a CD unusable. There is an error correction in the way data encoded into a CD, which ensures that minor scratches on the disc’s surface do not make the CD unreadable. CD / DVD players cannot read it unless the scratches are severe or the CD is cracked.