Table of Contents (click to expand)

There are a few possible explanations for why our jaws drop when we’re shocked. One theory is that it’s a vestigial response from our days before language, when we needed to communicate our emotions without words. Another possibility is that it’s linked to our body’s fight or flight response, and that dropping our jaw is the quickest way to take a deep breath of oxygen. Finally, it could be that we’ve learned to mimic common expressions, and that dropping our jaw is simply a habit we’ve picked up.

A magician pulls off an unbelievable trick right before your eyes. Our favorite character in a television show is unexpectedly killed off in dramatic fashion. A professional athlete makes a miraculous catch at the last instant against impossible odds….

What do all these events have in common? Well, for most people in the world, it would result in our jaw dropping in shock or surprise. We look a bit silly when we’re caught open-mouthed, but it seems to happen to people all over the world, even Blake Griffin, so don’t feel too embarrassed.

The fact that it happens in undeniable, but what’s more interesting, of course, is WHY our jaws seem to drop when something completely surprises us.

Recommended Video for you:

Communicating The Unexpected

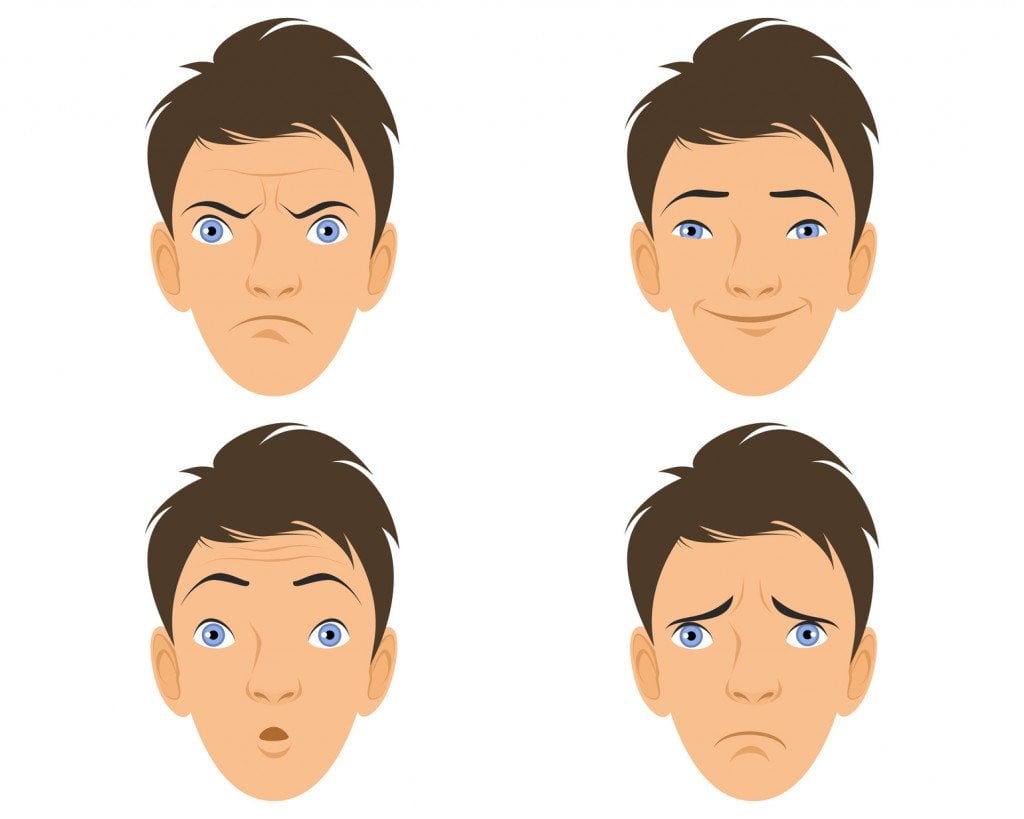

Despite the diversity of human beings on this planet, there are a few universal emotional responses that are found in cultures from here to Timbuktu. Anger, sadness, fear, and surprise are all signified by similar facial expressions by human beings. This is a remnant from the days before language, when people had to accurately communicate without the help of organized words and phrases. If we wanted to express an emotion that we were feeling, and have others understand us, then a uniform means of expression was needed.

Shock is closely linked to fear, so when something terrifies us, we often open our eyes wide and our mouth drops open, just as it does when something takes us completely by surprise. This tells other people around us that something frightening or shocking is occurring. While large-scale anthropological studies of this kind can be difficult and often deemed “inconclusive” based on the limited size of the subject group, this belief in the development of common expressions dates back to Darwin, who argued that, “Every true or inherited movement of expression seems to have had some natural and independent origin. But when once acquired, such movements may be voluntarily and consciously employed as a means of communication.”

This early form of emotional communication would have helped us protect others in our “tribe” or “family” by communicating the presence of danger – an important component of kin altruism and natural selection.

Related to this idea posited by the Father of Evolution is the facial feedback hypothesis, which basically suggests that facial movement and expression is closely linked to emotion, and can actually influence the emotional experience of an individual. Basically, we wouldn’t be able to completely “feel” the emotion of shock if we didn’t accompany it with the relevant emotional expression.

Fight Or Flight: Shock And Awe Edition

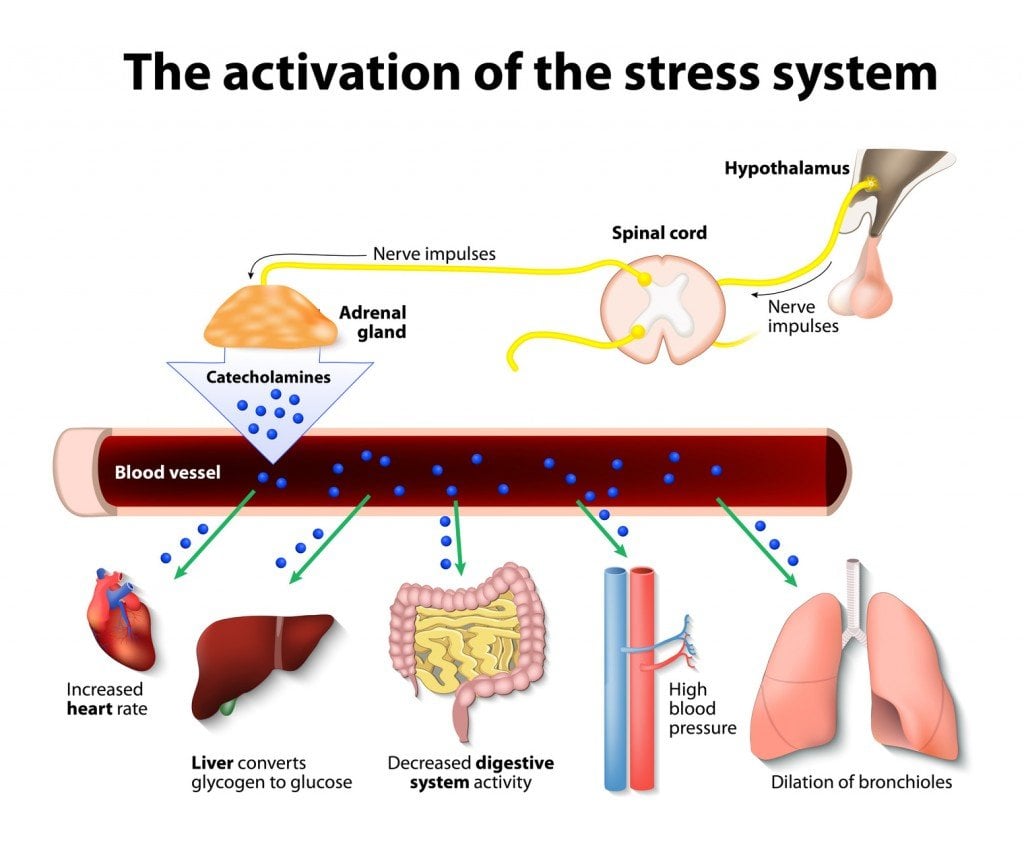

As mentioned above, surprise and fear are thought to be closely linked, and when we talk about fear, it’s almost impossible not to mention the body’s natural fight or flight response. For those of you who don’t know the details, the fight or flight theory was first proposed nearly a century ago, and suggested that in response to a fearful or dangerous situation, animals experience involuntary actions by the sympathetic nervous system – typically in the form of a release of stress hormones (adrenaline and norepinephrine).

This causes a number of physiological effects in the body, such as increased blood flow and breathing rate, and contracted muscles. Essentially, the body is ready to “fight” the perceived threat or take “flight” to avoid it. Both of those activities require a boost of adrenaline and energy, but some of the other physiological effects are less dramatic. Our jaws may drop open when we are shocked because the quickest way to draw a massive breath of life-giving oxygen is to open our mouth and suck in some air!

Our muscles need a huge influx of oxygen to contract and work efficiently when in a stressful situation, and the body naturally prepares itself to take in that air by leaving us open-mouthed. Although this was his opinion from 1872, Darwin also had some specific comments on this phenomenon: “We always unconsciously prepare ourselves for any great exertion, as formerly explained, by first taking a deep and full inspiration, and we consequently open our mouths.”

The Final Word

While Darwin’s wisdom is respected across the world, there are many behavioral scientists who have challenged his work in recent years, and have posited their own explanations of our emotional expressivity. Our jaw-dropping habits could be the result of an inherent stress response, a vestigial means of communication, or a culturally learned habit to mimic commonly accepted expressions, but a definitive answer is still elusive.

Research is still ongoing on the subject, so we must admit… science doesn’t have all the answers yet!

We know, it’s shocking, so pick up your jaw and move on with your life. Perhaps we’ll have the answer soon!