Table of Contents (click to expand)

The most likely reason humans lost their tails is because they began to walk on two legs. This would have made it difficult to balance with a tail. Additionally, tails would have been redundant once humans began to use tools and automation as they no longer needed them to swat bugs or help with balance.

Man, Darwin concluded in The Descent of Man, “despite his God-like intellect, which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system – with all these exalted powers – still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.” He was, of course, referring to our primate ancestry. We are just half a chromosome away from being copiously haired and perpetually hunched, from being what one might call a “beast”.

Evolution gradually pruned these traits, but nature isn’t as generous as you might believe. Being rigorously parsimonious, nature only deals in trade-offs. Less hair comes at the cost of feeling colder, while a lowered larynx, which enabled the vocalization of a gamut of sounds and therefore language — possibly the pinnacle of our evolution — made us more liable to choke when we talk while eating.

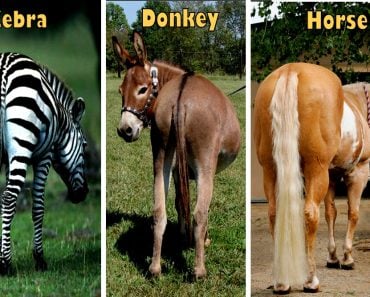

Another such trait is the tail. The tail is not an eccentricity — tied to their pelvis, it is found wiggling and undulating on a variety of animals, but particularly mammals. Apes and therefore humans are exceptions – monkeys did and have continued to flaunt them to date, but why did our common ancestor refuse to grow one? What we’re essentially asking is: what’s the trade-off?

Recommended Video for you:

Redundancy

A tail can serve multiple purposes: a horse uses it to swat bugs, a crocodile stores in it, just like a camel stores its body’s excess fat in its hump, fish use their fins to steer, while primates use their tails to hang and swing from branches. One reason why we then ceased to grow a tail is obvious: we ceased to swing from branches; we left the trees and embraced land. Of what use is a tail then? Why would we waste our time and resources nurturing this redundant appendage? So, we gradually evolved to suppress them.

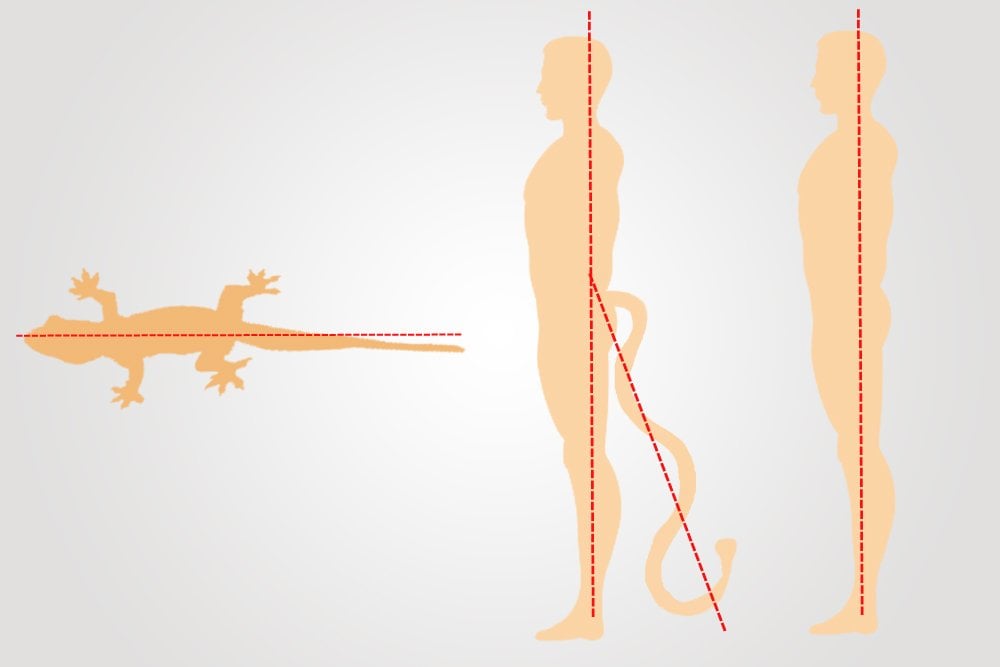

Not growing a tail became more favorable for survival because it would not disrupt our balance. Most tailed animals are tetrapods – they have four limbs. The tail can be moved by an animal to manipulate its center of gravity and therefore maintain balance. When our ancestors embraced living on the land, it is speculated that to achieve dexterity, to say, forage more effectively, they straightened or rose, beginning to walk on their hind limbs.

As our bodies gradually evolved to adopt a more vertical orientation than a horizontal one, tails would have surely disrupted our center of gravity, and therefore our balance. Walking upright with a tail would have been quite cumbersome. In fact, monkeys who walk on two legs often exhibit a stunted tail.

Walking on hind limbs did take centuries of practice. A long stick helped until one fine day, our hands were truly “free”. This pair of dangling hands would eventually be responsible for our greatest invention: tools. The invention of tools, or our ability to automate in general, competes with language to be crowned the sole arbiter of our unprecedented evolutionary success.

The Tailbone

Nature might be generous, but it definitely isn’t efficient. Like a bad investor, nature has absolutely no foresight; it only seeks solutions that work in the short term. The most punishing consequence of this lack of prudence is that the mistakes cannot be rectified, and we must live with them. Nature can only add; it can never subtract.

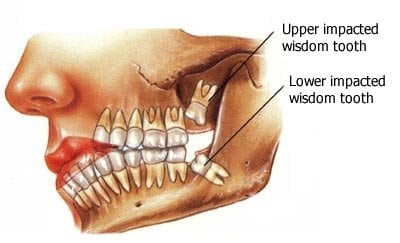

Consider our wisdom teeth, or the appendix, parts that were indispensable to us when we consumed a raw diet. However, subsequently, we began to cook food, which produced softer, more easily digestible meat. The inception of cooking or processing food undid two crucial developments simultaneously. We neither needed the wisdom teeth to chew hard, raw food, nor did we need the appendix to digest it.

However, because time and energy constraints don’t allow nature to remove these parts of the body, it has no option but to keep them. These once indispensable organs are now utterly worthless, only a potential source of immense agony that can be alleviated by surgical means. These are called vestigial organs, and the tail is another of them.

Yes, humans, being mammals, do grow a tail, but not for more than 30 days. An appendage comprising 10-12 vertebrae grows at the tip of the spinal cord from a bone appropriately named the tailbone. However, the genes responsible for its growth are turned off in the embryonic stage. After it stops growing, around the 4th week, it is outgrown by other tissues in the next 4 weeks, such that around the 8th week, the tail is effectively nonexistent.

However, children will often develop, like an extra thumb, a fifth appendage – a crude tail. These are cases of atavism, a rare biological occurrence in which an offspring will suddenly evolve traits shared by a distant ancestor, rather than shared with his or her parents. Basically, a millennia-old trait will unexpectedly reappear. These cases are not as rare as you’d believe. Of course, the discovery of a tail can elicit confusion, downright terror or, if you worship the Hindu god Hanuman, sanctity. However, for doctors, this is ordinary, and the protrusion is then removed surgically.

One case study I read involved six children aged between 2-3 days to 3 years, each born with a tail ranging from mere centimeters to, extraordinarily, inches. Interestingly, every tail wasn’t serpentine and slick like the tail of a rat; one was actually bobbed like the tail of a lion! This is the perfect example to illustrate nature’s fallibility and penchant for mutation.

The Unknowns

So, it seems we traded the tail for walking on our hind legs, sort of. The truth is, one can never determine precisely why a trait evolves or why it is repressed. We can only speculate and theorize. This seems to be the most logical reason, but we cannot say for sure. Who knows what adversity fell upon our ancestors some million years ago that pressurized his or her genes to repress the tail. It seems that survival could be salvaged only at the immediate cost of our tails. Who knows why we decided to walk on two legs?

What’s more, there is no single, particular gene that determines a tail’s growth, just like there is no single, particular gene to determine the color of your iris. Turning on a gene is like fiddling with a haphazard, inscrutable configuration of levers. The one we accidentally push may push another, which then pushes another, setting in motion a cascade of more unknown pushed levers. There are just too many variables involved.

In a few years or millennia, perhaps even the tailbone will disappear. However, until then, the tailbone and a plethora of other traits, such as our sharp canines or ever-drooping spines, represent archives of our wild evolutionary history. They are, as neurologist V.S. Ramachandran writes, “the grim reminders of our savage past”.

References (click to expand)

- Mukhopadhyay, B., Shukla, R., Mukhopadhyay, M., Mandal, K., Haldar, P., & Benare, A. (2012). Spectrum of human tails: A report of six cases. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. Medknow.

- Why Are Some People Born With Tails? | HealthGuidance.org. healthguidance.org

- Atavism: Embryology, Development and Evolution. Nature

- Why don't humans have tails? - Pursuit. The University of Melbourne