Table of Contents (click to expand)

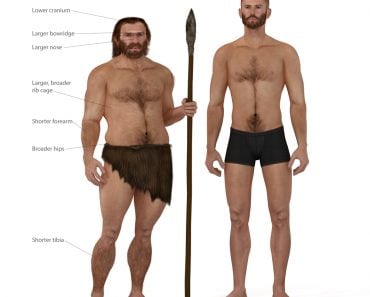

Human hairlessness is an evolutionary mystery. There are many theories out there, but two important ones are the savanna hypothesis and the ectoparasite hypothesis.

Humans are unique in many ways. We have the powerful tool of language, we have consciousness, and we have opposable thumbs. We conquered fire, water, air and even space. No other animal, not even the dinosaurs with their gargantuan size and sharp teeth could achieve this.

However, we are probably the most different from other animals, especially mammals, in terms of our hair, or lack of it, to be more precise. Why aren’t we furry like our closest living relatives—the bonobos, chimps, and gorillas?

Charles Darwin would answer this question with sexual selection. In 1871, in his book “The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex”, Darwin proposed the concept of sexual selection as “the advantage which certain individuals have over others of the same sex and species, solely in respect of reproduction.”

This means that the purpose of certain characteristics is largely for flirtation. These characteristics help an animal secure a mate over other competing individuals.

The Darwinian Homo sapiens lost their hair because males found less hairy females sexier. He reasoned that over generations of males picking less hairy mates, the overall population, of both males and females, became less hairy due to genetic mixing. This sounds like a logical argument when you have only half the facts. Darwin, the father of evolution, came up with the best explanation he could with the information on hand (and Victorian Era biases).

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do Animals Have Hair?

To understand the flaw in Darwin’s argument, let’s look at what evolutionary biology has unearthed today about hair.

Hair is a protein filament that grows from the dermis layer of your skin. Almost every mammal around us has a thick coating of hair or fur. Except for a handful of creatures, like the hairless mole rat (which only looks cute in Kim Possible, but is quite alarming in reality) and aquatic mammals like whales and dolphins, most mammals have hair. Land mammals evolved this hair because it gave them an edge on land.

Fur is a great insulator against heat. The hair traps pockets of hair between them, keeping the heat in when it’s cold outside. Piloerection, also known as getting goosebumps, is a thermoregulatory mechanism of increasing these air pockets. The arrector pili muscles cause the hair to stand up, thus forming air pockets.

The fur also protects the skin from the harmful UV rays of the sun.

Hair is an extended sensory tool. Something brushing up against hair moves the hair follicles, which send signals to the brain to pay attention. This helps when pesky parasites like bedbugs or mosquitoes are lurking around trying to suck your blood.

Even with all of this that we understand, figuring out why, how and when animals upgraded to hair is difficult. Evidence often comes from fossils, which aren’t great at recording soft tissue impressions.

The first undisputed evidence of hair comes from the fossilized hair impressions of Castorocauda, a semi-aquatic mammal that lived in the middle to late Jurassic Period (Callovian age). This puts the appearance of hair at least 164 million years ago (mya).

Another fossil found in Mongolia appeared to show fur on a mammal, and the researchers named this specimen Megaconus. All this evidence leads back to a common ancestor of mammals, the reptile-mammal—synapsids.

Why Have Humans Lost Fur?

Darwin’s explanation works perfectly fine in the modern world (more or less). Some males do find females with less hair more attractive, but some others might not. Another group might not care.

In all this, culture dictates attractiveness. This is where Darwin’s argument breaks down. Our hairlessness is not the only component for mate selection, as it is in male birds with vibrant plumage or odd dance rituals linked to mating. Darwin’s sexual selection hypothesis fails to specify what caused the hair loss in the first place.

While Darwin didn’t solve the mystery, he did open the floor for later evolutionary biologists to present their own theories. These figures didn’t disappoint.

The Savanna Hypothesis

The ‘Savanna hypothesis’ is the current favorite. Whenever research published supports or denies this theory, the science communication space scrambles to cover the shift. Proposed by Raymond Dart in 1925 after discovering the first Australopithecus skeleton in Africa, the hypothesis fits our visions of pre-man the best.

The hypothesis suggests that hominids lost their hair because having it became inconvenient. Out in the open (or closed?) savannas of Africa, with the sun beating down on them, cooling off would be a problem. Remember, body hair serves as an insulator. Keeping unnecessary insulation means the body must expend more energy to thermoregulate.

The Ectoparasite Hypothesis

At some point during any school year, a lice outbreak is bound to happen. Children come back itching and scratching at their scalp. I’m sure there is a certain mother out there that has thought about shaving off all their child’s hair just to avoid dealing with that potential risk. Mark Pagel and Walter Bodmer must have thought so too, as their hypothesis suggests that our ancestors lost all their body hair to avoid lice infestations.

Hair is a great place for lice and other ectoparasites to hang out. They not only suck on their host’s blood, but also carry diseases. Having less hair makes one an unsuitable habitation for such creepy crawlies.

Pagel and Bodmer suggest in their original paper that the trait started out being naturally selected for, as individuals with greater lice infestations might have died through disease, and the trait eventually got reinforced through sexual selection (Great! Darwin might not be wrong after all).

The Naked Love Hypothesis

Proposed by James Giles, this hypothesis suggests that human hairlessness increased a mother’s love for her child. Humans walking on our own two feet was a big moment in our evolution, but walking on two feet meant giving up those nifty prehensile feet that chimps and other great apes have. Young hominids wouldn’t have been able to cling to their mother’s fur without them, forcing the mothers to carry them.

The more motivated and loving a mother was towards her child, the more likely she would have been to carry her child. A lack of hair, which increases the pleasure of skin-to-skin contact, might make the mother love her child more, and therefore make her more motivated to carry it, thus giving it a better chance of survival.

The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis

At some point around 6 to 8 mya, hominids had an aquatic phase. Fur made swimming difficult and the hair no longer served as a great insulator. Thus, evolution decided to get rid of it. Although paleontologists have found remains of hominids near water bodies, there is no evidence that they ever had a completely submerged existence. Of all the theories presented in this article, this one holds the least sway in the scientific community at large.

None of these have provided a convincing answer, as there isn’t enough evidence to furnish that answer. Paleontologists don’t know what the hominid environment looked like at every step of evolution, nor how much of it looked like open grasslands (which every natural history documentary shows) versus thick tree cover.

The indirect means we use, such as carbon dating, fossils and skeletal records, don’t give us the entire picture. In fact, different pieces of the same puzzle can contradict research done in the past.

Today, hair is closely linked with our identity. The hairstyles we maintain and the decision to keep body hair or not is heavily influenced by culture. Humans now have fire, clothes, air conditioning, and pest control, allowing us to control our environment to a large degree. While we don’t know exactly how it came to be on our bodies in the way it is, hair has now become a cultural tool for self-expression!

References (click to expand)

- Meng, Q.-J., Grossnickle, D. M., Liu, D., Zhang, Y.-G., Neander, A. I., Ji, Q., & Luo, Z.-X. (2017, August). New gliding mammaliaforms from the Jurassic. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Ji, Q., Luo, Z.-X., Yuan, C.-X., & Tabrum, A. R. (2006, February 24). A Swimming Mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic and Ecomorphological Diversification of Early Mammals. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- (2003) A Naked Ape Would Have Fewer Parasites - JSTOR. JSTOR

- Giles, J. (2010, December). Naked Love: The Evolution of Human Hairlessness. Biological Theory. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. (2014, February). Is the “Savanna Hypothesis” a Dead Concept for Explaining the Emergence of the Earliest Hominins?. Current Anthropology. University of Chicago Press.