Table of Contents (click to expand)

Ancient snakes, dating back around 150 million years, actually did have legs. Fossil records indicate that the advent of the leg-less trend came about with a switch to more subterranean habitats.

We all feel for snakes. As cool as they are, with their venom-filled fangs or their rib-crushingly powerful constriction, most of us still can’t get over the fact that they have no legs. Yet, for an animal that has colonized every continent aside from Antarctica, snakes might be grateful for their leg-less existence.

Snakes are some of the most common animals in the world. From the tropics to the temperates, they do pretty well for themselves in most parts of the globe. Given their impressive range, they’re obviously highly successful in most habitats. Be it water, on the ground, deep within the earth, or even high up in the canopies, snakes are everywhere! So how did they achieve this magnificent expansion of range and habitat?

Recommended Video for you:

Have Snakes Always Been Legless?

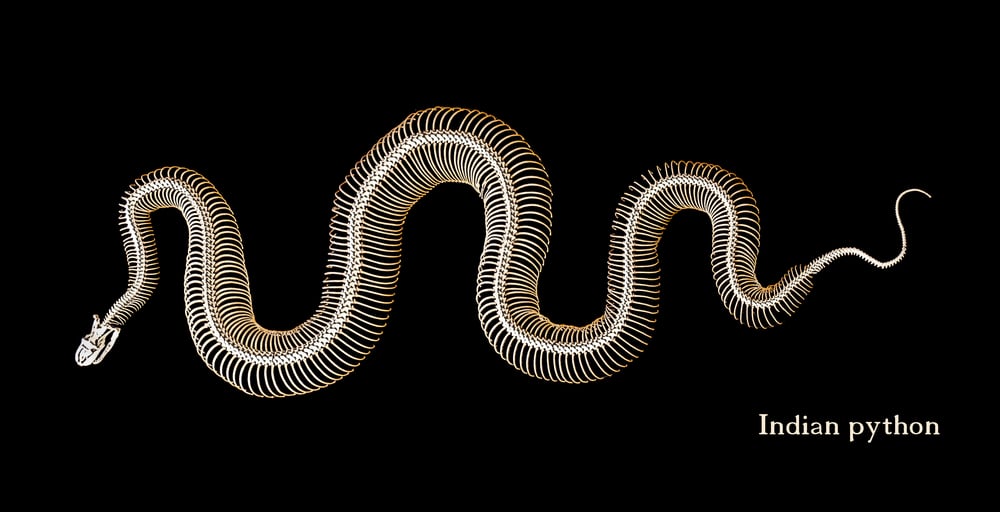

Ancient snakes, dating back around 150 million years, actually did have legs. However, as we can obviously see today, snakes either don’t have any legs (like cobras and vipers) or have tiny and redundant vestiges of legs (like pythons and boas).

So, what happened between 150 million years ago and today?

Researchers from the University Of Florida were able to identify a gene, which they enthusiastically named Sonic the Hedgehog, that controlled limb development in snakes (and all legged vertebrates). When they identified the gene, the researchers noticed quite a bit of strange activity.

While all living vertebrates have the “Sonic The Hedgehog” gene, in snakes, this gene is switched off. Stranger still is the fact that the gene briefly switches on during the embryonic development of baby pythons, specifically baby pythons that are less than 24 hours old.

What Does This Mean?

We can draw quite a few conclusions from this unusual activity of the Sonic The Hedgehog Gene.

The main conclusion is that this brief activation of the Sonic The Hedgehog or SHH gene during the embryonic development of baby pythons and boas is what is responsible for their vestigial buds or legs.

The activation and inactivation of the gene give us two evolutionary paths taken by snakes. Snakes like boas are “ancient”, in the sense that they still display this brief activation of the SHH gene, whereas more “recent” snakes like cobras do not activate the SHH gene at all.

In both “ancient” and “recent” snakes, what has led to the reduced or non-existent activity of the SHH gene comes down to parts of the DNA called enhancers. In ancient snakes, parts of the enhancers were either deleted or reduced, whereas in “recent” snakes, the enhancers responsible for contributing to limb development along with the SHH gene were virtually undetectable.

Does this mean that “ancient” snakes have an edge over more “recent” ones?

Not at all. The legs of a python are about as useful as a wheel on a ship. They’re just small black nubs with claws. They don’t do anything beyond provide some insight into the evolutionary history and genetic mechanisms that define snakes.

Did “Ancient” Snakes Evolve Before “Recent” Snakes?

Ancient snakes simply refers to a branch of divergence. The name doesn’t really mean that an ancient snake is older than a more recent one (in terms of the geological time scale, not the general passage of time). For example, we can refer to two fossil records from the Late Cretaceous period, namely the Dinilysia patagonica, and the Najash rionegrina. Both of these extinct snakes lived approximately 90 million years ago. The Dinilysia patagonica was a terrestrial snake that lacked legs, while the Najash rionegrina was technically a legged snake (though the legs were more rudimentary and small, as opposed to fully developed legs that can actually bear an organism’s weight).

Based on other fossils of extinct snakes from that time, what we can definitively conclude is that any leg-bearing snakes didn’t actually use their legs for any form of locomotion, such as swimming or walking. Therefore, as early as the late Cretaceous, we can say that snakes were in the process of switching from a legged form to a leg-less form.

Why Did Snakes Go Leg-less?

Snakes are evolutionary rogues. Fossil records indicate that the advent of the leg-less trend came about following a switch to subterranean habitats. While living underground, limbs are a bit of a liability. Think of it like this: how much easier would it be to fit into a tiny nook, crevice, or hole without 4 radiating structures—legs and arms—poking out from the sides of your body?

This legless, elongated, and tapered body also complimented other modes of locomotion, like swimming. They even figured out a nifty way to scale (literally, scale) vertical surfaces!

In an article published on the Florida State Parks website, Keith Morin, a park biologist at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, said it best:

“From the way they move, to the places they can go and some of the methods of subduing prey, like constriction, having legs would simply get in the way. Over millions of years they gradually lost legs, and they’ve even lost shoulders and hips. Evidence of older species with limbs can be found in the fossil record and in the boas (Boidae), a more primitive family that still has remnants of limbs.”

So yes, snakes do benefit from a lack of legs. However, as with most things in evolution, the answer isn’t always a clear one-liner. A legless form isn’t the only reason or evolutionary advantage that snakes picked up along the way; other morphological changes like tapering and elongation of their bodies also helped. After all, remember that snakes are true evolutionary rogues!

References (click to expand)

- Leal, F., & Cohn, M. J. (2016, November). Loss and Re-emergence of Legs in Snakes by Modular Evolution of Sonic hedgehog and HOXD Enhancers. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Why Don't Snakes Have Legs?.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352573815300111

- H ZAHER. (2009) anatomy of the upper cretaceous snake Najash rionegrina ....