Table of Contents (click to expand)

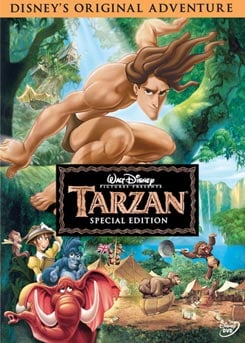

Tarzan was raised by apes, in which case, could he have been able to understand Jane, let alone speak to her?

“No, no, no. I am Jane,” Tarzan repeats, after learning Jane’s name in the iconic Disney movie. However, consider this: Tarzan had not been in the company of humans since a very young age. Would he have actually been able to speak to Jane at all?

To determine the answer to this question, we need to deep dive into how humans learn to speak.

Recommended Video for you:

How Do We Learn A Language?

Babies learn to talk by listening to adults speak. We do not attend classes to learn how to speak; we pick it up from our environment. Babies begin speaking by making random, meaningless sounds. This is called “babbling” and starts as early as 7 months of age in normal children.

However, there are exceptions to this rule. Deaf children do not start babbling by this age, because they are unable to hear others speak and therefore lack exposure to speech by adults. However, when they are taught sign language, they can “babble” like other infants of the same age, but in sign language!

Thus, deaf babies are perfectly capable of learning language. They’re unable to speak only because they don’t receive speech input through hearing. This proves that humans can only learn language through exposure to hearing speech. Any issues that cut off this language input can affect language learning.

A Critical Period In Language Learning

Scientists suggest that our ability to absorb language through hearing others speak only lasts for a couple of years in childhood. This window of time where we can pick up language is called the “critical period”.

The exact age at which this critical period of language learning ends is widely debated. However, scientists agree that this ability almost always shuts down by puberty. What makes this period “critical”?

During the critical period, the brain is highly “plastic”, meaning that the brain can modify itself and absorb new skills easily, since it’s still developing. The ability to do this falls sharply after puberty because the brain’s development is almost fully complete. This explains why we’re better at learning new languages at a younger age than we are later in adulthood.

You might have noticed that people who manage to learn languages at later ages are seldom able to sound as “native” as those who learn it in childhood. This shows the magic of the “critical period”!

Now, you might ask, didn’t Tarzan miss his chance to learn language during this critical period?

When discovered by the ape—Kala—baby Tarzan had no clearly developed language, but is shown to be babbling, which is an appropriate language milestone for his age at that time. Realistically, his language development would have frozen at that point. It’s not possible for a babbling baby to develop further language on its own without external input.

Feral Children

The role of the “critical period” in language learning came into the limelight after a number of studies conducted on feral children. Tarzan, the protagonist, is the most familiar fictional example of a feral child.

Feral children are those who grow up away from human contact and civilization, in the wild. In the real world, the first reported case of a feral child was in Germany in 1724. It was a 12-year-old boy named “Wild Peter”; he was mute and showed animal-like mannerisms.

Similar to deaf children, feral children provide an opportunity for scientists to understand how language development progresses when an individual is deprived of speech input. In almost all cases, feral children grow up with little or no language input during their “critical period” of language learning.

This “language deprivation” has a lasting impact on their brains and cognitive development.

Reported cases of feral children show that they’re usually unable to learn language even when rehabilitated to live normally with humans. These studies provide proof for the critical period of language learning. Once we pass beyond the critical period, even when provided with the required input, our brain is unable to incorporate new skills, such as language.

In contrast to these reported cases, Tarzan is shown to be speaking to Jane when he first finds her in the movies. Based on the evidence from reports, we now know that this is almost impossible. Feral children found around 12-13 years of age are unable to learn speech after exposure. A full-grown adult like Tarzan, whose brain has crossed the critical period even further, will not be able to learn to speak from Jane.

However, feral children are reported to be capable of producing non-speech sounds, such as mimicking animals, a skill they pick up from their environment. This could mean that they communicate effectively with their animal companions, as Tarzan is seen to do with gorillas in the movie.

A Final Word

It is best to take stories like this with a pinch of salt—or perhaps a whole shaker!

Fictional works like Tarzan show human babies raised in isolation being able to speak language although in a limited capacity. However, real-world examples of such feral children show that this is almost impossible. Children deprived of human speech input, such as the hearing impaired or feral children, grow up to have little or no language ability. These situations allowed scientists to understand the importance of exposure to language input in learning to speak.

We are capable of picking up language purely from our environment, without any explicit teaching, but this ability is limited to the early years of our childhood up until puberty, called the “critical period” of language learning. Feral and deaf children lack language input during this critical period, thereby ending up with limited language capability.

In the light of these findings, it’s safe to say that Tarzan would not able to speak to Jane; he would have been basically mute, like real-world Tarzans or feral children!

References (click to expand)

- The Development of Language: A Critical Period in Humans. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1981). Speech and Brain Mechanisms. []. Princeton University Press.

- Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018, August). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition. Elsevier BV.

- Loffstadt, H., Nichol, R. J., & De Klerk, B. (2006). A feral family on our doorstep. South African Psychiatry Review, 9(4), 231-234.