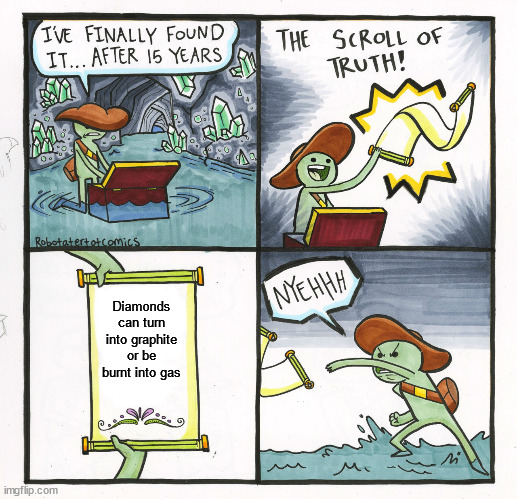

Theoretically, diamonds will last forever. Chemically, they won’t. Graphite is a more stable form of carbon, so a diamond would eventually transform into graphite… but there’s more to the story than that.

The origin of the word “diamond” comes from the Greek word adamas, which means “unconquerable, invincible.” First discovered sometime in the 4th century B.C.E., some of the most valuable diamonds in the world have been dated, and found to be formed 100 million to even billions of years ago. To possess these eternal diamonds, humans have resorted to nothing short of treachery (see: blood diamonds of Africa).

All this blood and glory for a shiny rock… that isn’t actually unconquerable or invincible.

Yes, diamonds are not forever. Instead, they can transform into the coolest mundane object imaginable – graphite. Yes, the same graphite that’s found in your pencil.

On the other hand, diamonds can simply burn to carbon dioxide.

So, why would diamond covert to graphite or burn? And how long can a diamond really last?

(Spoiler alert: The diamond in your wedding ring will be fine, but the diamond you use to cut metal will most certainly not be fine.)

Recommended Video for you:

Diamond Is An Allotrope Of Carbon

Alone, carbon is simply carbon, an element with an atomic number of 6, and it is a non-metal.

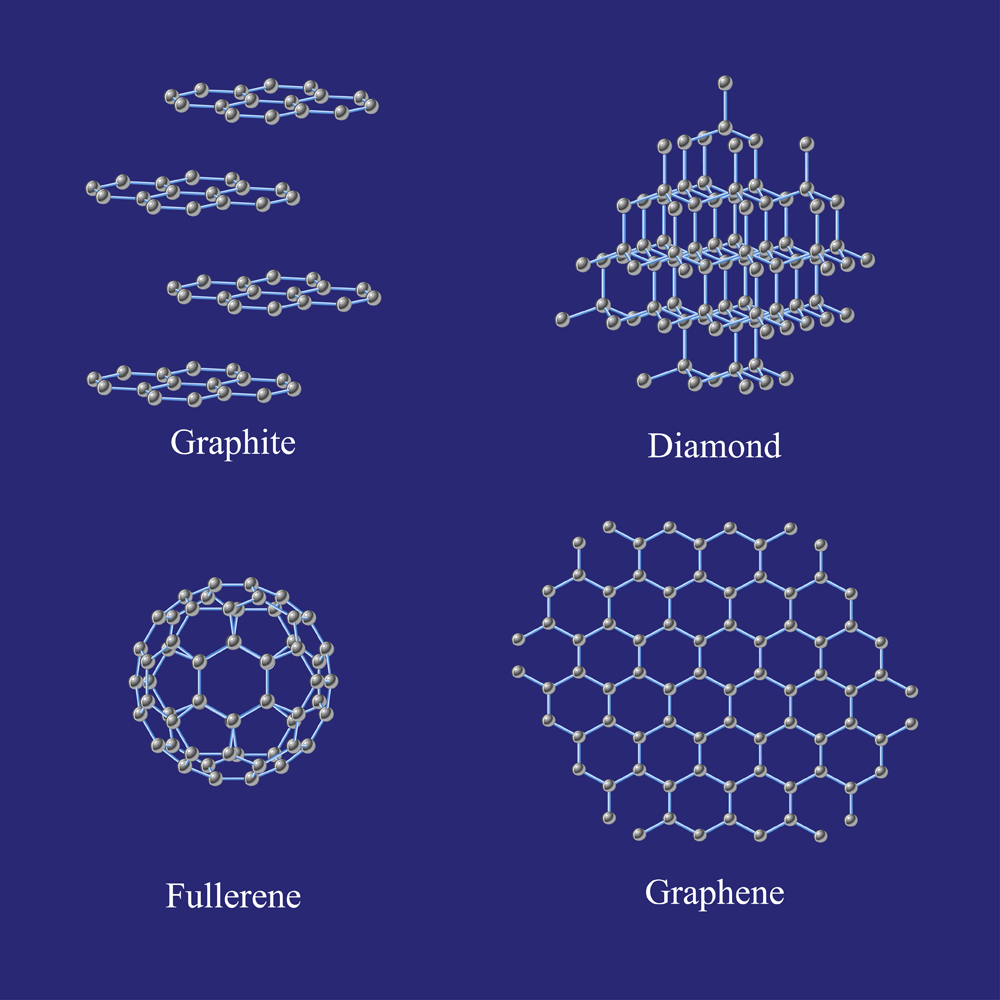

However, when carbon links with other carbon atoms, it can create a myriad of structures, each with a unique set of properties. These different forms are called allotropes.

Allotropes are a speciality of non-metallic elements like carbon, silicon, and phosphorous (which has 6 allotropes).

Carbon, however, has a slew of allotropes due to its valency. Carbon has four available electrons to share with other elements to create compounds. This valency gives it a unique flexibility to contort into different structures when bonded with other carbon atoms.

Diamond takes an octahedral structure, in which each individual carbon atom will attach to four other carbon atoms in a sort of three-sided pyramid structure.

Other carbon allotropes form sheets (graphite and graphene), spheres (buckminsterfullerene) and even some odd nano-structures.

Graphite, Not Diamond, Is The Most Stable Allotrope Of Carbon

Although diamond’s tetrahedral structure makes it the hardest substance known to man, it is not the most stable form of carbon.

That title goes to graphite.

You see, diamond is the metastable structure of carbon. Metastable in chemistry means that a structure is more or less stable under certain conditions, but an even more stable state does exist.

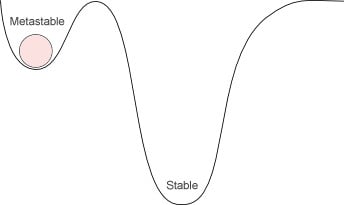

A common analogy is to think of a ball rolling down a valley. The most stable place for the ball would be at the bottom of the valley (as can be seen from the deeper valley in the picture below).

Now, imagine the ball gets stuck in a smaller well (the smaller valley in which the ball can be seen).

The ball is stable in the smaller well, but since the well is higher than the bottom of the valley, this is not its most stable state. However, the ball will remain there unless work is done to get the ball out of the well and to the bottom of the valley.

Our diamond is like that ball in the well, while graphite is the ball at the bottom of the valley.

In chemistry terms, diamond is kinetically stable because it’s nicely trapped in the well, but it is thermodynamically unstable, because there is the more stable form of graphite to which it could convert, given the right conditions.

So, Why Don’t Diamonds Convert To Graphite?

So, if there is a more stable form, why haven’t all the diamonds on Earth turned into graphite? There are two reasons for that.

First, diamond is stable at the condition present on Earth. Furthermore, graphite is only a few electronvolts more stable than diamond (on Earth). The difference in the stability of diamond and graphite isn’t all that much.

Second, the energy needed to convert diamond to graphite is large.

In other words, the energy needed to get the diamond out of the well and down to the bottom of the valley, where it will turn into graphite, is very large.

Chemists and geologists have tried to convert diamond to graphite in the past. They found that upon compressing a diamond with an indenter (basically a pointy thing to poke the diamond with), the surface of the diamond in contact with the indenter changes to graphite.

If squishing a diamond isn’t your style, scientists have also found that low pressure and very high temperatures (1500 to 1900 degrees Celsius or more) will work. Add iron to the mix and it will further hasten the process (called graphitization).

However, don’t expose diamonds to high pressures if you want to convert them to graphite. Diamonds are more stable under high pressure than graphite, which is how they’re formed in the Earth’s mantle (and even on some asteroids!). However, under certain conditions, diamonds might convert to graphite even under high pressure.

How Long Do Diamonds Last?

Considering what we explained above, the diamond on your engagement ring or in the Queen’s of England’s crown will likely last forever.

However, if you’re using your diamond as a tool to cut or grind things, especially things made of iron, then you might want to pay attention.

The part of the diamond in contact with the iron (or whatever else the diamond is cutting) might get heated enough to convert into graphite. If even tiny bits of the diamond turns into graphite every time you cut something, the diamond will, eventually, completely turn into graphite.

Or, you could simply burn a diamond with as little as a magnifying glass and the sun. Two people, naturalist Giuseppe Averani and medic Cipriano Targioni of Florence, in 1694, did just that. They took quite a large magnifying glass and focused sunlight onto a diamond—only to watch the stone disappear before their eyes!

Knowing how easily manipulable a diamond is, and how little separates a precious diamond from the graphite in our pencils, should make us reevaluate what we deem valuable and treasured in this world!

References (click to expand)

- (1964, January 21). A study of the transformation of diamond to graphite. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Gogotsi, Y. G., Kailer, A., & Nickel, K. G. (1999, October). Transformation of diamond to graphite. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Diamond - Molecule of the Month. bris.ac.uk

- Occelli, F., Loubeyre, P., & LeToullec, R. (2003, February 2). Properties of diamond under hydrostatic pressures up to 140 GPa. Nature Materials. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Narulkar, R., Bukkapatnam, S., Raff, L. M., & Komanduri, R. (2009, April). Graphitization as a precursor to wear of diamond in machining pure iron: A molecular dynamics investigation. Computational Materials Science. Elsevier BV.