Table of Contents (click to expand)

Demography is not destiny. Having an aging population is not necessarily a curse, while a youthful population is not necessarily a blessing. Policies play a critical role in determining economic growth.

In 1900, on average, men died two years after they stopped working. By 2000, on average, it was 20 years after they stopped working.

What changed in 100 years that caused a tenfold increase in the retirement duration for workers?

The answer to this is wider access to healthcare and education, both of which generally lead to better living standards.

Planning and forecasting are required to navigate such systemic shifts resulting from demographic changes. The findings of demographic studies have built systemic capacity to endure a growing or declining population.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Demography?

Demography is the study of population size, growth, and age structure. Simply put, it is the study of the population composition.

Every resource must be examined to ensure effective utilization. Land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship are the key inputs in any production process. Labor, as a resource amongst others, starkly stands out, as it is resources that play a significant role in the production process, and ultimately, it is also the labor for whom everything is produced. Think of consumers.

However, consumers do not imply only labor, but also dependents. Dependents comprise the population that is not of legal working age. This refers to young children and the aging population.

To sustain any population, systems must be built to cater to the needs of both the working and dependent populations.

The focus is primarily on two indicators—fertility and mortality rates. The fertility rate denotes the average number of children a woman has in her fertile years. The mortality rate is the number of deaths per 100,000 humans.

There are other indicators, too, such as birth rate, life expectancy, and natural growth rates. However, we will only be looking at the two broad and commonly interpreted rates—fertility and mortality.

All these rates are called demographic indicators. They provide a crucial overview of the population, and their movements determine the components of change in the forthcoming years.

Is Demography Destiny?

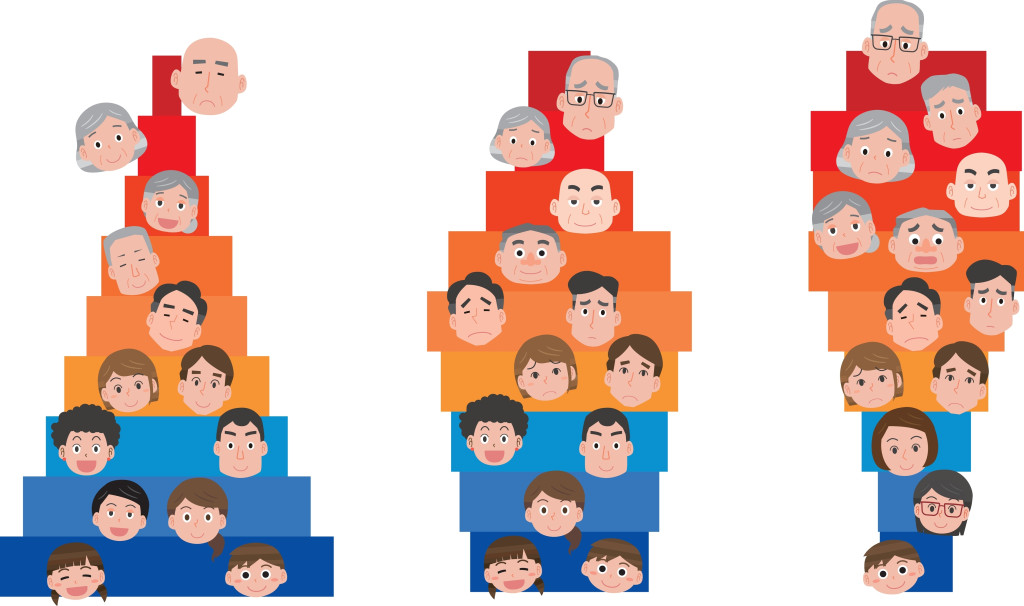

‘Demography is destiny’ is often famously quoted because it is the composition of a population that dictates policy design. For instance, some countries have a high proportion of older populations; this raises the question of whether there are enough savings in the economy to sustain that “top-heavy” population. The older demographics are no longer a part of the working age group, but can the young working population shoulder payments to the older population for pensions, insurance and other social security measures? If not, the taxation rates need to be revised.

This is one of many other questions that economies face when looking at demographic indicators. This also does not necessarily imply that an aging population is a burden or that a robust working-age population is a boon.

The influence can go the other way too. Economic policies can equally influence demography. Think of China’s one-child policy, imposed from 1979 to 2015, which helped bring the total fertility rate from 6 per woman to just under 3. This intended to control the population, and it worked, but only to that extent. It had severe ramifications on the gender composition of the economy, as males were preferred to females, coupled with rising abortion rates and the abandonment of female babies.

Furthermore, it also led to a rise in the aging population and a shrinking working-age population.

Therefore, there is a close interplay of forces between policy and demography, as they are both equally influenced by economic incentives, as well as social and cultural norms and behaviors. Policies must be designed with all these factors being considered.

What Is The Impact Of Demographic Changes On An Economy?

Population growth is examined to understand the rate at which the overall population of any country is growing. The rate dictates systems for food, clothing, housing, medical services and other infrastructure that need to be simultaneously built.

The next focus is to understand the dynamics of the population – its composition. This can be examined through the fertility, mortality and birth rates.

A country is said to be experiencing a demographic dividend when birth rates, child death rates, and fertility rates are low, while most of the population is of working age.

The dependency ratio—the ratio of the dependent population (non-working population) to the working-age population—is low during a demographic dividend. This is so because with fewer births, fewer child deaths and lower fertility rates, there is a reduced dependency on the working-age population. With a reduced burden of the dependent population, resources are freed up for investments, rather than consumption being the sole focus.

Economies yearn for a demographic dividend. They design policies to catalyze their transitions so that they can experience economic growth. This does not imply that a demographic dividend is a necessary and sufficient condition for economic growth; it needs to be backed by sound macroeconomic policies and a stable political environment.

Once an economy experiences a demographic dividend, the benefit sticks around for five decades or more. The effects of economic growth can extend even further, based on the investment decisions made by the population during their youth. If assets are accumulated through savings and investments, this will continue to add to the economy’s national income.

The period of experiencing a demographic dividend can also be extended. The extension depends on the kind of savings and investments the aging population has committed to during their working years. If they do not invest or save, it can send the economy towards disaster, as it becomes the responsibility of the youth to shoulder the survival of older demographics through income support, resulting in high taxation. Hence, the benefits from a demographic dividend are not necessarily guaranteed or automatic!

References (click to expand)

- (2010) Demography and the Economy | NBER. NBER.org

- Changing Demographics and Economic Growth – IMF F&D. Dana Moneter Internasional

- Demographic Changes and their Macroeconomic Ramifications in India. Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

- Kim, J. (2016, September). The Effects of Demographic Change on GDP Growth in OECD Economies. IFDP Notes. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Fact Sheet: Attaining the Demographic Dividend | PRB. Population Reference Bureau

- What Is the Demographic Dividend? - Finance & Development. International Monetary Fund