A particle accelerator is a large machine that is used to perform physical experiments involving high-energy, subatomic particles. Particle accelerators come in two types: linear and circular accelerators. The basic functionality of a particle accelerator is to accelerate particles close to the speed of light using electromagnetic fields and contain these speedy particles in well-defined beams.

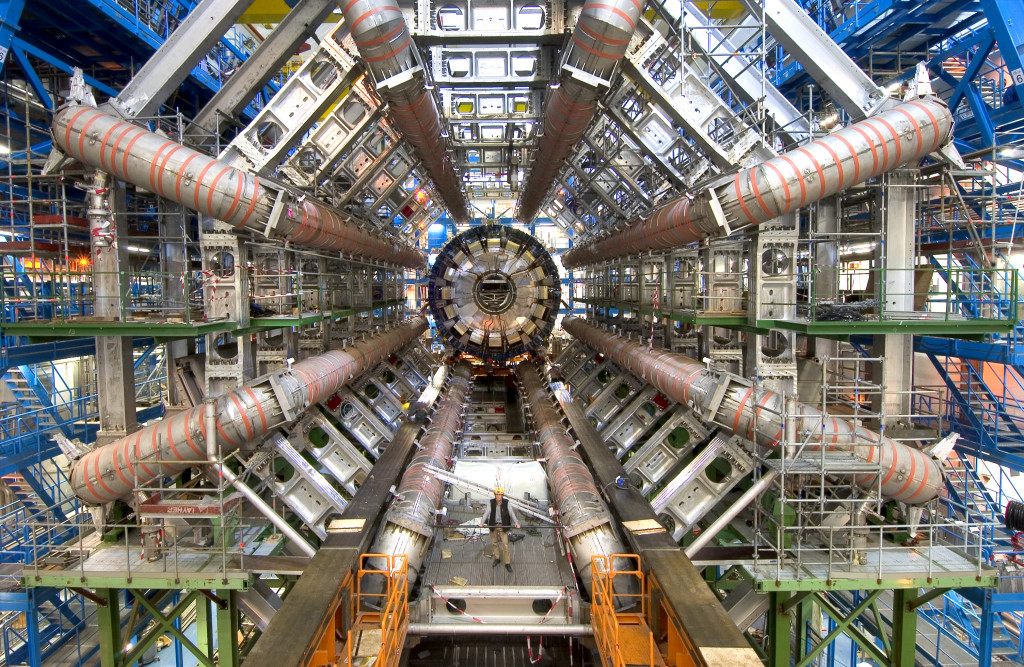

You have probably read about or heard of particle accelerators in numerous scientific discussions, especially those pertaining to particle physics. For the record, they deserve more attention than they get! For example, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – a particle accelerator – is the single largest machine ever built by mankind. That staggering fact might make you wonder… what is it actually? And perhaps more importantly, why should I care what it does?

First things first…

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Particle Accelerator?

A particle accelerator, in the most basic terms, is a large machine that is used to perform physical experiments involving high-energy, subatomic particles. For more technically-inclined minds, it is a device that accelerates charged particles close to the speed of light using electromagnetic fields and contains these speedy particles in well-defined beams.

Some of the most famous particle accelerators include the Large Hadron Collider (two different ones operating in ion mode and proton mode), the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, Tevatron, J-PARC, BEPC II, etc.

Contrary to what many people believe, the Large Hadron Collider is not the only particle accelerator in the world; there are actually hundreds of particle accelerators operating all over the planet that serve different purposes, including scientific research, medicine and even international security. (Source)

What Does A Particle Accelerator Do?

Particle accelerators basically come in two types: linear and circular accelerators. Despite the differences in their design and mode of operation, the basic functionality remains the same.

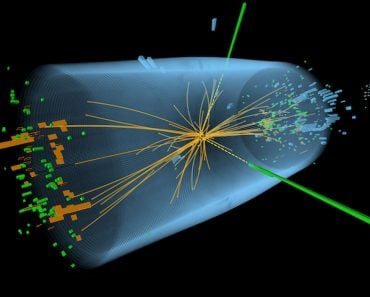

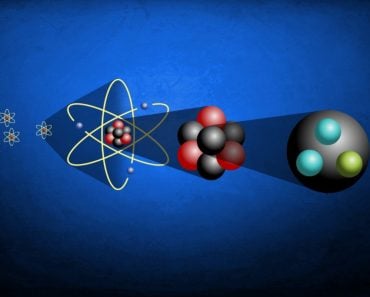

The particle source (like a hydrogen nuclei) provides the desired particle (e.g. proton, electron etc.) that researchers want to accelerate. The particle is then accelerated through a vacuum inside a metal beam pipe using very powerful electric fields. Once the particle starts moving, strong electromagnets steer and keep the beam of particles focused in the metal pipe, which eventually strikes another beam coming from the opposite direction or a stationary target. Note that the vacuum inside the metal tube is incredibly important, because when you’re dealing with subatomic particles traveling near the speed of light, you want to ensure that there is nothing – not even air molecules – that could potentially obstruct their path.

To put the concept in perspective, consider this: while taking a walk one day, two identical stones come crashing down to Earth right in front of you. Being a curious person, you take the stones to your house and try to figure out what’s inside them (because they are unusually heavy for their size and have a somewhat alien appearance). However, the stones are so strong that you can’t break them open to see what’s inside.

As a last resort, you smack the stones against each other as hard as possible, and lo and behold! The stones shatter and their internal bits and pieces fly out!

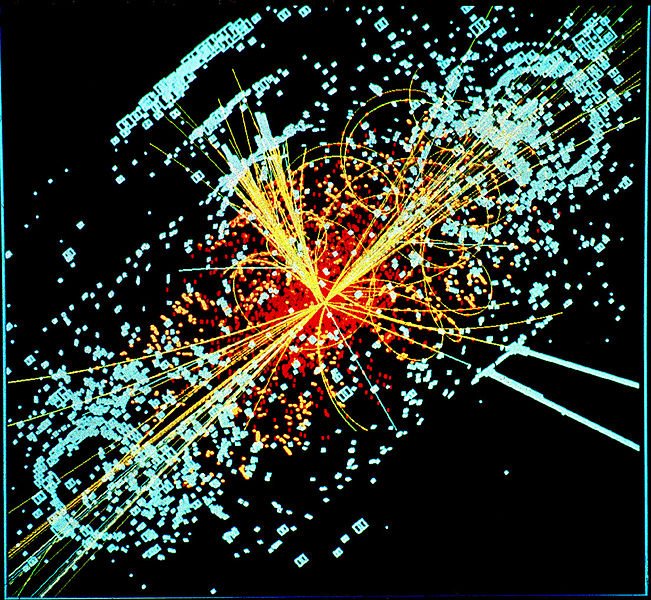

Something very similar to that happens in a particle accelerator, where subatomic particles (that are very small and extremely strong) are smashed together in a tube to see what’s inside them (e.g., pions, baryons, mesons etc.). The difference, of course, is that these particles are accelerated to nearly the speed of light and are smashed together millions of times.

The Higgs-Boson particle, aka ‘The God Particle’, was discovered in the LHC through the same process after trillions of collisions were carried out within the tube.

Smashing two stones together is a very basic analogy, and the actual working of a particle accelerator is far more complex. For a more detailed explanation, check out this article by CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research.

Why Are Particle Accelerators Important, And Why Should You Care About Them?

From their photos and how they function, it might seem like particle accelerators are only relevant for bespectacled physicists and lab rats who are obsessed with going deeper and deeper into exploring the nature of matter, but particle accelerators are actually quite helpful for human society, which makes them very desirable.

Particle accelerators, through the production of radioisotopes, help diagnose millions of diseases in people around the word. In addition to that, radioisotopes are also used to kill malicious tissues inside the body, (e.g., cancer) by using microwave linear accelerators.

Particle accelerators have a number of applications in the industrial sector as well; they help to seal your milk carton tightly, and they also help in making chips that allow your computer to be staggeringly faster than older models. They continue to revolutionize the consumer market by contributing to trailblazing discoveries at the subatomic level of the most common things that surround us.

All of these benefits of particle accelerators stem from the fact that they can help us unravel the mystery and power of materials and particles by going beyond what we’ve been able to achieve thus far. They have helped us understand more about our universe, as well as the fundamental laws that make up the fabric of our very existence.

All in all, what we ‘do’ know is that particle accelerators are very, very cool and have tremendous potential to change the world, but we haven’t discovered all the ways in which they can be leveraged. By the way, you should also know that one of the many hypothetical roles that a particle accelerator can play is that of a time machine, according to Stephen Hawking himself, one of the world’s leading authorities on the concept of time travel.