Table of Contents (click to expand)

Simply scooping out all the plastic from our oceans sounds easy, but is an extremely complex challenge. There are many considerations, such as the emissions of the ships used to scoop out the plastic and the potential by-catch of fish and other marine organisms that would impact the ecosystem.

We have found plastic in every corner of the world we’ve look at, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, from the highest points on land to the deepest oceans.

Since its first use in 1907, plastic has been silently tightening its grasp over our planet and all its ecosystem inhabitants. Based on a 2017 study published in Science Advances, about one-third of all plastic waste is dumped in nature, and only 9% of it gets recycled in the US. About 75% of the plastic gets thrown away, which is equivalent to 4900 metric tons of plastic, or 11 Boeing 747-8 passenger airliners.

All plastic ends up harming the environment where it is released or disposed of; animals get caught in it or end up consuming it. Since plastic doesn’t decompose, it will persist in the environment for decades, if not centuries. One solution is to remove the bigger pieces of plastic, such as water bottles and plastic bags, from natural spaces. This is easy to do on land, as we can simply walk over and pick up the piece of plastic.

But what about the 75 to 199 million tons of plastic matter that’s already in the oceans?

To address this issue, The Ocean Cleanup, a Dutch non- profit, has taken the matter into its own hands, committing to cleaning up the plastic present in marine water bodies by literally “scooping out” the floating plastic trash from the oceans.

How efficient is this process, and how will it impact marine life?

The bigger picture demands us to rephrase the question from, “Can we scoop out the plastic from the oceans?” to “Should we be scooping out the plastic at all?”

Recommended Video for you:

The Amount Of Plastic In Our Oceans

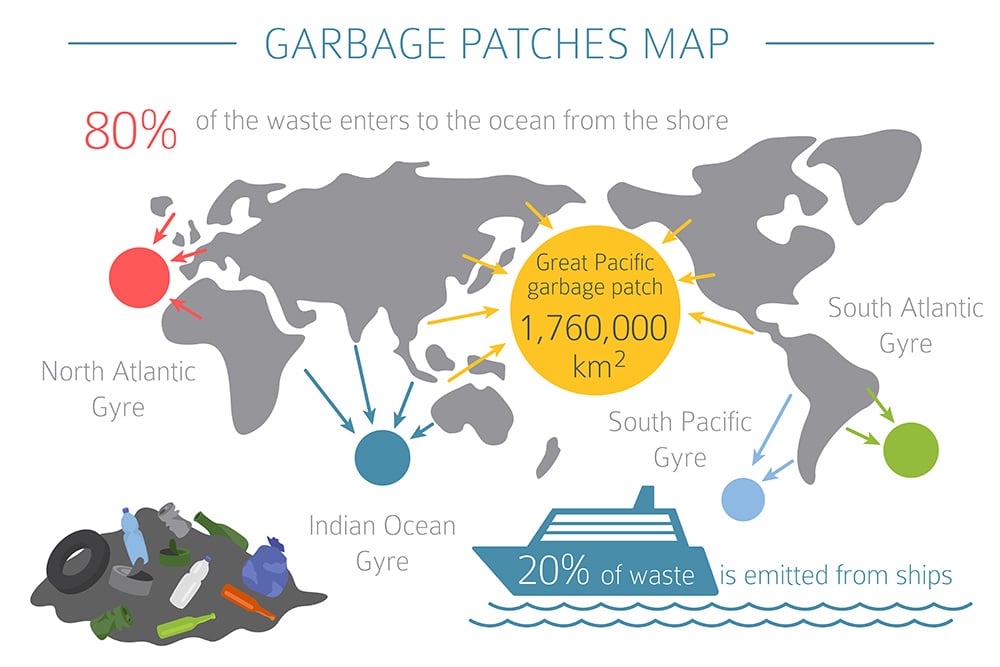

Plastic in our ocean is everywhere, but the majority is concentrated in patches due to rotating oceanic currents (gyres). There are five such gyres and garbage patches, the most famous of which is The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, covering 1.6 million square kilometers.

The others include a patch in the Indian Ocean, two in the Atlantic, an another in the Pacific Ocean.

Each gyre has garbage patches of various sizes.

Floating plastics caught in these patches will continue to circulate until they disintegrate into smaller fragments, making it increasingly challenging to clean up. Plastic bags are frequently mistaken for jelly fish, a favorite food of loggerhead sea turtles. Albatrosses feed plastic resin pellets to chicks because they perceive the pellets to be fish eggs. The chicks eventually starve to death or suffer organ rupture.

Research shows that most of the plastic litter spiraling into the gyres and the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is decades old, but it turns out that more recently produced plastic remains closer to coastlines. This suggests that one of the best ways to deal with ocean plastics may be through beach cleanups.

The Ocean Cleanup

The goal of The Ocean Cleanup is to remove 90% of the floating plastic waste in the ocean and to make the Great Pacific Garbage Patch “garbage free.”

Its latest and most functional cleanup technology, System-002, consists of a three-meter-deep, floating net-like barrier that forms a large U. The system in question is propelled by Maersk ships.

However, what gets overlooked is that the large ships used to drag the collection net have a sizable carbon footprint. Dragging nets through ocean water with massive ships powered by fossil fuels adds to air and climate pollution. In their own Environmental Impact Assessment report, it can be seen under Section 5.0 that the two vessels operated by The Ocean Cleanup release 600 metric tons of carbon dioxide per month of cleanup, which is comparable to over a hundred cars on the road for an entire year.

There is also a bycatch issue (trapping marine animals whilst collecting plastic). Free-floating plastics are tricky to scoop out from the water without entangling fish, turtles, and other marine wildlife. Even when they are thrown back into the water, these creatures usually die. Organisms that get entangled in fishnets suffer a hampered ability to find food and evade predators. Even if the organism doesn’t actually die, injuries, limitations on movement, and a reduction in their foraging capacity will seriously harm the animal.

Scientists have expressed concern about the effects that this passive collection technology may have on the neuston, a type of biota that dwells on the Pacific Ocean surface (this research was funded by The Ocean Cleanup).

Snails, crabs, sea dragons, and jellyfish are all a part of this ecosystem. These creatures are frequently found living on the surface of plastic waste. As an integral part of the food web, neuston establishes significant ecological links between various oceanic communities. For instance, the neuston serves as a nursery habitat for young fish species, such as Atlantic cod and salmon, and is the primary food source for endangered species like loggerhead turtles.

Riverine Plastic Pollution

According to a 2017 study, the global riverine system currently discharges 1.15 to 2.41 million tons of plastic into the oceans annually. The top 20 polluting rivers were mostly in Asia, where they impact 21% of the world’s population and more than two-thirds (67%) of the annual global input. In addition, more than 90% of the plastic inputs came from the top 122 polluting rivers, with 103 of them being in Asia, eight in Africa, eight in South and Central America, and one in Europe.

From the rivers to our drinking glasses, plastic has made its way into our guts. Drinking water, including bottled and tap water, is the most significant contributor of plastic in the human diet, with the average person ingesting about 1,769 tiny microplastic particles every week, based on a 2019 report backed by the WWF.

To curb this source of marine plastic pollution, The Ocean Cleanup has additionally deployed solar-powered vessels called Interceptors at the mouths of plastic-polluted rivers. Trash is gathered by a barrier as the water flows, is transferred to a conveyor belt, and then dumped into a shuttle, which transports the trash to a waste management facility. Eight Interceptors have already taken out more than 2.2 million pounds of plastic from rivers in the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

As of October 2023, we have no data on what the impacts of this approach are.

Conclusion

The Ocean Cleanup strategy is new, but the ironical damage it creates on the environment is not something we should ignore. The best approach to scooping out the plastic from the oceans is to “not focus on the scooping part,” but to focus on the original source of the plastic.

Today’s throwaway culture promotes single-use plastic usage. Of the 300 million tons of plastic produced each year worldwide, half of it is for single-use items. Cans, water bottles, food containers, and anything else you use once and throw away are a huge part of the problem. Identifying this problem at its root is the most efficient way of solving it without letting it escalate beyond our control, to the point where cleanup efforts are futile.

References (click to expand)

- Cressey, D. (2016, August). Bottles, bags, ropes and toothbrushes: the struggle to track ocean plastics. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Lebreton, L. C. M., van der Zwet, J., Damsteeg, J.-W., Slat, B., Andrady, A., & Reisser, J. (2017, June 7). River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nature Communications. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- 565 Proxy Handshake Failed - 10.1126

- No pLAStIc IN NAture:.

- Vered, G., & Shenkar, N. (2021, September). Monitoring plastic pollution in the oceans. Current Opinion in Toxicology. Elsevier BV.