Table of Contents (click to expand)

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological scenario in which the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of an individual are at odds with one another. The brain undergoes significant activity to resolve this dissonance (conflict), most often by changing the attitude of the person so that their behavior and beliefs once again align.

It’s a weekday night, you have homework due tomorrow, but also want to watch a TV show that’s been the talk of the town. You decide to throw caution to the wind and get cozy in bed to watch the show.

However, while watching the show, there’s an uncomfortable itch at the back of your head, like something is just not right. You know that you should really start your homework if you want to complete it before going to bed, but nevertheless, you can’t seem to stop watching the show!

There is a clear conflict between what you think you should be doing and what you are actually doing, and this contradiction makes you very uncomfortable.

This feeling of discomfort has a name: cognitive dissonance.

When our actions are wildly disparate from our thoughts, there is a discord in our brain that generates this dissonance.

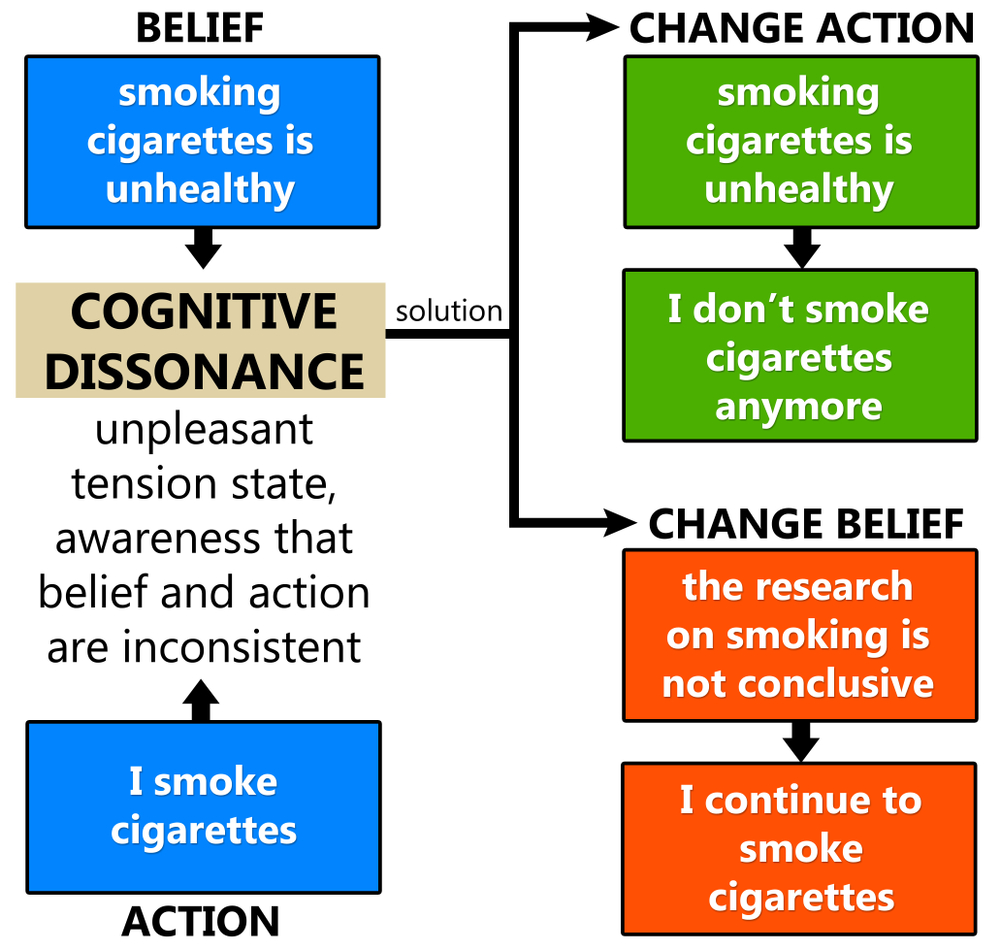

Another example of an activity generating cognitive dissonance is that of smoking.

It is widely known and understood that smoking is injurious to health, but smoking remains a notoriously popular habit. Knowing that smoking is an unhealthy activity, but being unable to give it up creates dissonance in the mind.

As we know, if an itch makes us uncomfortable, we don’t just sit with it, we scratch it! Similarly, our brain has a few tricks up its sleeve to resolve the uncomfortable itch brought on by these types of conflicting emotions.

Recommended Video for you:

Discovery Of Cognitive Dissonance

Leon Festinger, an influential American social psychologist, put forward the theory of cognitive dissonance in the mid-1950s. It all began when a newspaper article caught Festinger’s eye.

The article narrated the bizarre story of a particular Mrs. Keech (actually known as Dorothy Martin). According to the story, mysterious extraterrestrial beings had contacted Mrs. Keech and brought with them the news of imminent doom: that a great, inevitable flood would destroy the world on a specific day—December 21, 1954, to be precise.

But all was not lost. These extraterrestrial beings had also, very kindly, intimated to Mrs. Keech that a flying saucer would rescue all true believers on the day the world was to end. Very quickly, a group of followers joined Mrs. Keech. Together they prepared for the end of the world, giving away all their possessions and even leaving their families and jobs.

Festinger was especially interested in the behavior these individuals would showcase after the supposed doomsday came and went, when the believers would have to face the falsity of their beliefs. To investigate this, Festinger and his colleagues disguised themselves as people who believed in the prophecy and gained entry into Mrs. Keech’s group of believers.

The predicted doomsday rolled in and rolled out, and the world kept plodding along. Following this obvious disappointment, the believers then proceeded to demonstrate unusual behavior. Since Mrs. Keech had received the prophecy, the group had kept a low profile and seemed entirely disinterested in engaging the press or media in their activities. However, after their prophecy was not fulfilled, they overwhelmingly sought out social support for their beliefs.

Festinger had actually hypothesized this outcome before infiltrating the group. He backed up the prediction by suggesting that after the group had realized their beliefs to be untrue, to reduce the discomfort they felt in facing a reality that starkly clashed with their ideals, they turned to fervently attempting to convince others of their beliefs by spreading their ideas through the media.

Even more interesting is that the people who were not fully invested in the prophecy, but were still participants of the group, didn’t have much trouble in accepting the prophecy as false. The people at the core of the group, who had invested a great amount of time in their beliefs and made extensive sacrifices for them, were the ones ardently clinging to their ideals. This showed that the more invested one is in their beliefs, the harder it becomes for them to face a truth that proves their beliefs wrong.

Festinger’s Cognitive Dissonance Experiment

Festinger backed up the above anecdotal data with a pioneering experiment, known as Festinger and Carlsmith’s classic experiment. The participants of this study had to perform monotonous and banal tasks, which included filling, emptying, and refilling a tray with spools and turning pegs in the clockwise direction repetitively. To make the task even more boring, they had to do these activities for an extended amount of time.

The participants had been divided into three groups: a control group that just performed the tasks, a group that received 20 dollars for completing the tasks, and another group that received one dollar. After the completion of the tasks, the participants in the groups were asked whether they found the experiment enjoyable; the control group and the group that received 20 dollars declared the experiment to be exceedingly boring.

The participants in the group that received one dollar, however, had quite different answers to this question. They stated that they had enjoyed the tasks.

The participants who were paid 20 dollars did not need to justify their actions; they had been sufficiently compensated for having invested their time in a tedious activity. Alternatively, the participants who were paid one dollar did not feel adequately compensated for having performed the tedious task for such a long time.

Hence, to provide some rationale for having spent this time doing these tasks, they pretended that the tasks were indeed fun. Therefore, since these participants could not justify their behavior, they resolved their internal conflict by changing their attitude (believing that the tasks were enjoyable).

What Happens In Our Brains During Such Dissonance?

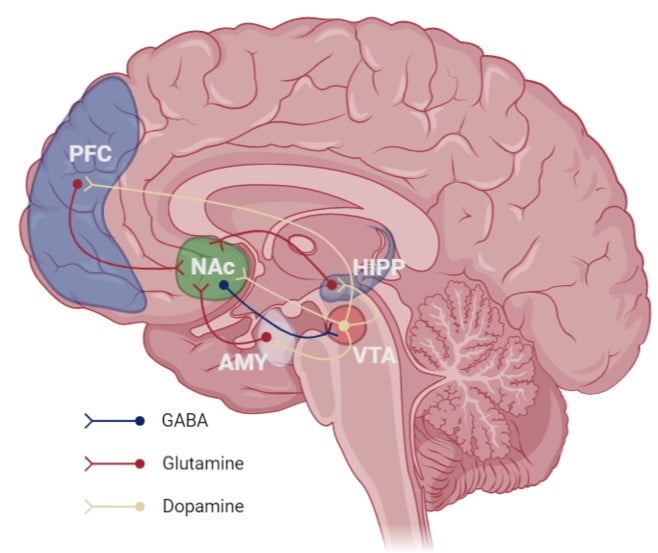

The brain region most implicated in relieving cognitive dissonance is located slightly at the rear end of the front part of the brain, known as the posterior medial frontal cortex (pMFC). Magnetic resonance imaging detects heightened activity in this area when a person is trying to justify their own decisions to themselves, especially when the decisions might not agree with their thoughts.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a technique that uses a magnetic coil, placed next to a person’s head, for either increasing or decreasing neuron activity. When this technique is used to decrease the activity of the pMFC, a marked reduction is seen in the propensity of individuals to change their mindset to agree with their actions, as well as their desire to create and maintain a consistency between the two (source).

Other brain regions involved in our battle to alleviate any cognitive dissonance we feel are those areas associated with intense negative emotions, such as anger and sadness, as well as those connected to cognitive control, like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). In fact, reducing the activity of the DLPFC using transcranial magnetic stimulation decreased the need of individuals to rationalize and justify their beliefs in cognitively dissonant scenarios.

Conclusion

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological scenario in which the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of an individual are at odds with one another. The peculiar aspect of this phenomenon is that during its occurrence, the brain undergoes significant activity to resolve the dissonance (conflict), often by changing the attitude of the person so that their behavior and beliefs once again align with one another.

There are ways that cognitive dissonance is helpful for us, such as ensuring that we’re at mental peace with the decisions we have made and are satisfied with our choices. However, it might also lead us to irrationally justify our actions and not face the reality of our choices because of how uncomfortable the resultant dissonance might make us feel.

References (click to expand)

- Buckley, T. (2015, October 15). What happens to the brain when we experience cognitive dissonance?. Scientific American Mind. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (2nd ed.).. American Psychological Association.

- Izuma, K., Akula, S., Murayama, K., Wu, D.-A., Iacoboni, M., & Adolphs, R. (2015, February 25). A Causal Role for Posterior Medial Frontal Cortex in Choice-Induced Preference Change. Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience.