Table of Contents (click to expand)

Mustard gas is a chemical agent best known for its use in World War I that is highly toxic, but rarely fatal. It results in a variety of painful symptoms and its use as a weapon is banned under the Geneva Protocol.

There are few aspects of humanity more horrific than war. Our history is littered with blood-drenched battlefields and destruction, lessons that are too often unheeded or forgotten. One of the most terrible truths of warfare, however, is that our methods of killing have steadily increased in their efficiency, impartiality, and lethality since the first prehistoric caveman bashed another over the head with a stone. From clubs, swords, and bows to guns, bombs and drones, our species has been on a singular trajectory towards the mastery of death-dealing for millennia. Some of the darkest and most unconscionable weapons mankind has created are those of a chemical nature, and perhaps the most famous example of this is mustard gas.

Its use in wartime is banned by the Geneva Protocol and it hasn’t been widely used since World War I, yet even the phrase “mustard gas” sends a chill racing down certain spines a century later—what is mustard gas and why is it so famous?

Recommended Video for you:

The Rise Of Chemical Warfare

Chemical weapons may seem like a modern invention, but they have actually been around for thousands of years, since ancient Greek city-states were poisoning each other’s water supply. Warring factions have dipped their arrows or coated their bullets in poison, and toxic fumes have been directed towards enemies when the winds are right. Using whatever means available to destroy an enemy has often been the mantra during wartime, but chemical warfare was perfected in the early years of the 20th century.

A greater understanding of chemical sciences and chemical periodicity allowed for the development of these weapons. Basically, once we were able to isolate different elements, followed by testing interactions and measuring subsequent characteristics, it was only natural to weaponize chemistry in a more formal way than poisoning an aqueduct with poisonous plant extracts. Various countries and chemists developed mustard gas in the 19th century, but it didn’t receive its first application in warfare until July of 1917. Two years earlier, the Germans had first used deadly chlorine gas against its entrenched enemy, and the Brits attempted to use gas as a counterbalance as early as September of 1915.

Chlorine gas smells of bleach and irritates the eyes, nose, mouth and throat, and can asphyxiate victims if they are surrounded by high enough concentrations. However, chlorine gas generated a strong smell and a greenish cloud, so detecting it was easy, and inhalation could be avoided by simply covering the nose and mouth with a damp rag, given the water-soluble nature of the toxin.

Phosgene gas was next, and was almost six times more deadly than chlorine gas, in addition to being colorless and having a less distinct aroma. The effects from this gas could take up to 24 hours to manifest, which made it less of a debilitating weapon on the actual battlefield, unless it was combined with chlorine, which the Germans did for the first time in December of 1915. With each iteration, the gases were become more effective and deadly, but they would culminate with the first use of mustard gas—the most effective chemical agent of The War to End All Wars.

Mustard Gas In World War I

Mustard gas turned out to be the favored choice among battlefield commanders in that epic conflict, though the exact numbers of its lethality during that campaign are unknown. In total, there were about 1.3 million fatalities caused by gas attacks, and an estimated 100,000 deaths. Most of these deaths were the result of using phosgene gas, referenced above, while many of the worst fatalities were caused by mustard gas.

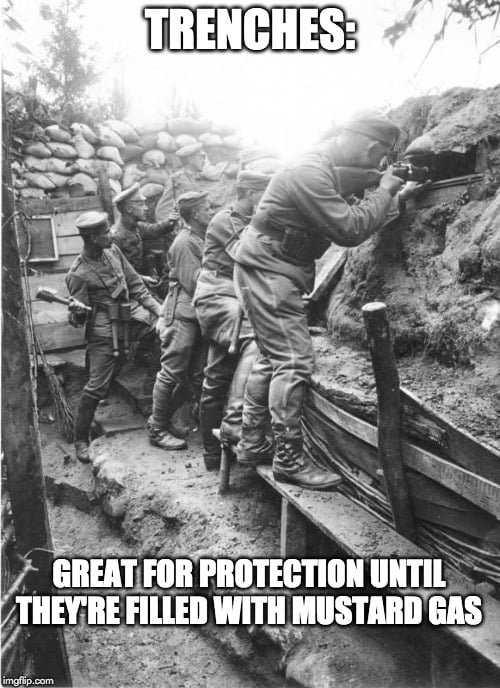

Mustard Gas As A Vesicant

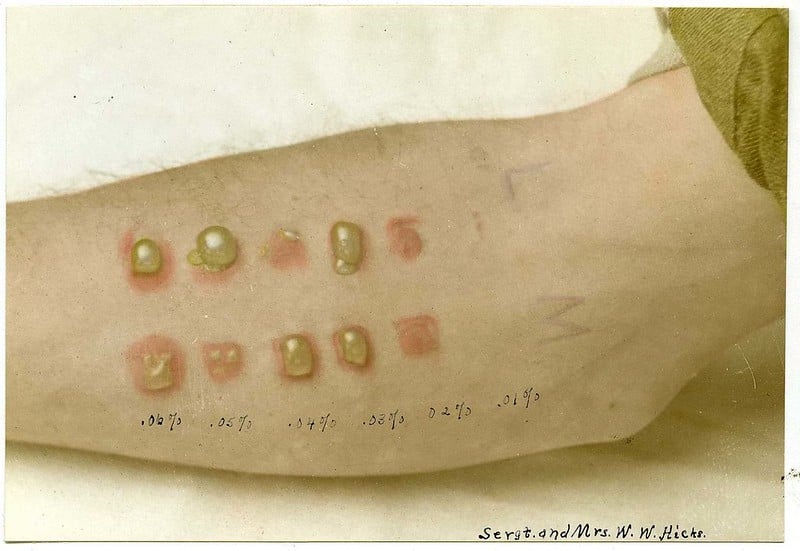

Mustard gas is also known as sulfur mustard and is a vesicant, capable of forming large blisters on both the skin and the inside of the lungs. When used in warfare, the gas was a yellow-brown color and had the faint odor of mustard, though others report it as being similar to garlic or horseradish. It is dispersed as a fine mist of droplets, and is not fully vaporized, but the name “mustard gas” stuck. The volatile gas was heavy, and would eventually settle on the ground as an oily liquid, but also formed dense clouds that descended into the trenches and stayed there, brutally affecting those who stayed in place or experienced extended exposure.

Having your eyes, nose, mouth, skin, throat or lungs exposed to mustard gas would result in extreme irritation, including nausea and vomiting, temporary/permanent blindness, shortness of breath, cough and sinus pain. It could feel as though your throat was closing, making it impossible to breathe, for weeks at a time as the severe symptoms played out. In some cases, it could take weeks for victims to die, or they survived and had permanent damage as a result of their exposure. This is also a mutagenic substance, meaning that it could attack the DNA of a victim, making them at far greater risk for cancer later in life, if they survived the horrors of that war.

Mild exposure to the gas could delay the onset of symptoms by 1-6 hours, but intense exposure was debilitating immediately, and the gas did not dissipate quickly. In some cases, it would be safer to move to the top of the trench, where you were susceptible to gunfire, rather than standing in a cloud of pooling mustard gas at the bottom of a restrictive trench. In some cases, the use of this gas made it impossible for an enemy to advance on a position, knowing that the gas was still lingering and would endanger their troops.

The Central Powers were not the only ones to employ gas attacks during this conflict; by November of 1917, the Allies were also launching mustard gas attacks against the Germans. Once the United States entered the war, the mustard gas manufacturing capabilities of the Allies greatly increased, and the chemical weapon tide of the war shifted.

After The War

In 1925, seven years after the end of the war, the Geneva Protocol was signed and ratified by most of the world within 5 years. One of the major points was a ban on the use of chemical weapons, such as mustard gas, as the signing countries declared that the use of asphyxiating weapons in war was “condemned by the general opinion of the civilized world”. For this reason, there was a surprisingly small number of gas attacks perpetrated in World War II, despite the total fatality figures being about four times greater in WWII (17 million vs 60+ million).

It was quickly seen that the use of countermeasures, such as gas masks, could easily be employed by both sides of a conflict, effectively rendering the toxic gases less useful, with the exception of some topical discomfort on exposed areas of skin. That being said, mustard gas has been used more than a dozen times in smaller conflicts since WWI, most notably in the Iraq-Iran War in the late 1980s, since it remains highly effective against an army that is unable to defend against such an attack. The use of chemical weapons is now considered a war crime, and is quickly renounced by the majority of the world in those rare modern occurrences, i.e., the sarin gas attack in Ghouta during the Syrian Civil War in 2013.

A Final Word

In terms of consistency, human beings (particularly those in power) can always be trusted to work on a bigger, faster, stronger and deadlier weapon, whether that is traditional, chemical, biological or nuclear. The development and deployment of mustard gas remains a horrific example of cruelty in wartime, and the lack of humanity that can be displayed for enemy combatants. Fortunately, the violent, insidious and long-lasting effects of this weapon were recognized and banned, but as we’ve seen time and time again throughout our history, it is truly impossible to put Pandora back in the box.