Table of Contents (click to expand)

The proportions of nutrients in fruit do change as it ripens. For example, the sugar content in fruit increases as it ripens, while the vitamin C content and the concentration of antioxidants increases as well.

When you go to the grocery store and re-stock your house with fruits and vegetables, it’s hard not to feel like you’re making a heathy choice for the week ahead. As we all know, fruits and vegetables are a critical part of a healthy diet, and provide a wide range of essential nutrients, from key vitamins and minerals to antioxidants, sugars and dietary fiber.

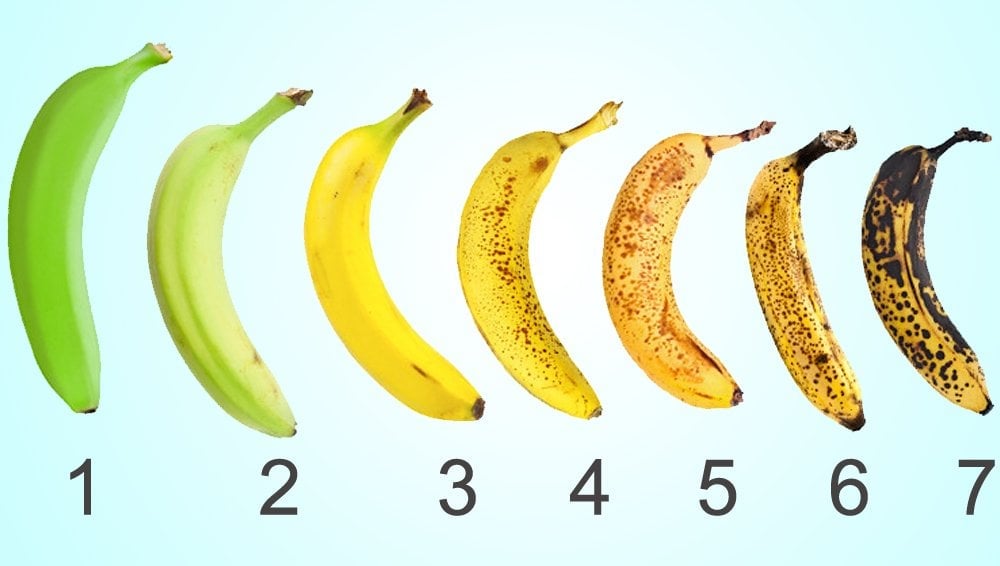

However, as that week progresses, your fruit may continue to ripen, often changing color or firmness over time. Bananas are perhaps the best and most visually demonstrative example of this, but all fruits undergo a ripening process (sometimes on the vine, and sometimes after being picked). This has led many people to wonder whether those physical changes in a fruit also affect its nutritional content. In other words, is there a nutritional difference between ripe and unripe fruit?

However, as that week progresses, your fruit may continue to ripen, often changing color or firmness over time. Bananas are perhaps the best and most visually demonstrative example of this, but all fruits undergo a ripening process (sometimes on the vine, and sometimes after being picked). This has led many people to wonder whether those physical changes in a fruit also affect its nutritional content. In other words, is there a nutritional difference between ripe and unripe fruit?

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do Fruits Ripen?

Before we dig into the details of what happens during ripening, we should take a look at why the process occurs at all. First of all, a fruit is effectively a container for the seeds of a plant, and develops from a flower. Basically, when a flower releases its pollen, this is done in order for other plants to be fertilized. Pollen is taken from the male part of a plant and brought to a female part of the plant. When this is completed, fertilization can begin and the flowers will begin to drop off.

Fertilization leads to the development of plant seeds, which need to be protected as they develop. The fruit that develops around the seeds will provide this protection, while also acting as the distribution tool for the seeds to grow. For example, after fertilization, a fruit will begin to grow around the seeds, but that fruit is said to be “underripe” until the seeds are fully developed and capable of growing into another plant if given the right soil and climatic conditions.

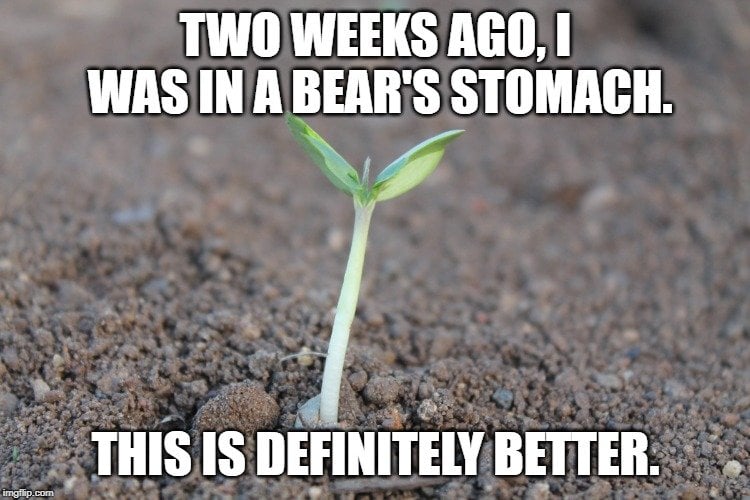

The ripening process is a form of growth, as well as a defense mechanism. When a plant is unripe, it will often be sour, overly fibrous, or even toxic to consume. Animals won’t want to eat that sort of fruit, and will therefore leave it alone. Once a fruit becomes “ripe”, it will often be sweeter, more colorful, and generally more appealing to a potential consumer. When the animal eats this sweeter, more attractive fruit—whether it is a bird, squirrel, bear, human or any other creature—it will then deposit those seeds elsewhere, after they pass through their digestive tract or are disposed of on the ground. By that point, the seeds will be viable and can grow into a new plant!

The ripening process is a form of growth, as well as a defense mechanism. When a plant is unripe, it will often be sour, overly fibrous, or even toxic to consume. Animals won’t want to eat that sort of fruit, and will therefore leave it alone. Once a fruit becomes “ripe”, it will often be sweeter, more colorful, and generally more appealing to a potential consumer. When the animal eats this sweeter, more attractive fruit—whether it is a bird, squirrel, bear, human or any other creature—it will then deposit those seeds elsewhere, after they pass through their digestive tract or are disposed of on the ground. By that point, the seeds will be viable and can grow into a new plant!

What Does Ripening Do To A Fruit?

As mentioned above, the ripening process often consists of a change in color, firmness and sweetness, all of which can signal that a fruit is ready to be eaten. Those physical changes are also reflected in a nutritional shift, primarily an increase in sugars. Many underripe fruits have a high starch content, which can make the fruit bitter or inedible, but as the fruit ripens, those starch molecules are converted into sugars.

The easiest example of this is a banana; green and underripe bananas do not have the recognizable sweetness and softness of a ripe banana. The conversion of starch into sugar gives the banana a higher percentage of sugar, as well as a better texture for eating and including in recipes. Sugar content is the most notable nutritional change between unripened and ripened fruit, but it’s not the only one. Vitamin C, for example, has been shown to increase as you allow peppers and tomatoes to develop to full ripeness.

In many other fruits, the antioxidant concentration will also improve as a fruit ripens. Considering that these are critically important nutrients for our body’s defenses, particularly against cancer and other forms of oxidative stress, getting more antioxidants in ripe fruit is definitely a good thing! That being said, this isn’t completely true across the board; some antioxidants (e.g., anthocyanins) will increase, while other antioxidant classes (e.g., phenolic compounds) will drop as a fruit ripens.

The good news, for those who love green bananas or green tomatoes, is that the nutritional change is rather minor. The calorie count of fruits does not change once they are picked from a tree, only the form that those calories take. Furthermore, mineral content rarely changes throughout the ripening process, so a green banana will still pack a potassium punch, even if it lacks the typical sweetness.

A Final Word

Rather than focusing on the ripeness of fruit to try and manipulate your diet into being healthier, consider the many other factors that can affect the quality and nutritive value of your food, such as whether a fruit is in season, or if it has been frozen. Some other factors to think about include the fruit’s time to market, as well as the temperature and humidity it has been exposed to during the shipping process. Eating ripe fruit is almost always more enjoyable, from a taste perspective, and it should have the same or an greater effect on your health as eating an underripe fruit.

While it may be true that ripe fruits have more sugar—a potential issue for diabetics trying to watch the glycemic index of their foods—the majority of fruits have a low GI score. Even bananas, with a glycemic index of 51, are considered safe for diabetic patients. Some of the higher GI fruits, such as watermelon, cantaloupe, mango, papaya, pineapple and other exotic fruits, can be eaten in moderation, in conjunction with talking to your doctor about your specific case and sugar intake. Generally speaking, the benefits of eating ripe fruit, regardless of your belief system, far outweigh the cons!

References (click to expand)

- Does Sugar Content Rise as Fruit Ripens?. livestrong.com

- Does Underripe Fruit Offer Less Nutrition?. The New York Times

- The Glycemic Index Table of Fruits Vegetables. healthyeating.sfgate.com

- Jenkins, D. J., Wolever, T. M., Taylor, R. H., Barker, H., Fielden, H., Baldwin, J. M., … Goff, D. V. (1981, March 1). Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Elsevier BV.

- Gierson, D., & Kader, A. A. (1986). Fruit ripening and quality. The Tomato Crop. Springer Netherlands.