Table of Contents (click to expand)

Research has shown that the older we get, the quicker we get tired. This might have something to do with the wear and tear on our tissues and individual cells.

I remember as a child wanting to stay up all night on the weekends. I used to whine and convince my parents to play games with me. They’d politely comply, but would yawn every now and then. I remember them saying, “We’re not young anymore, we don’t have your energy.”

As we lose our youth, we seem to get tired more easily, but why? Even if we live our healthiest lives and eat a healthy diet with regular exercise, our energy levels inevitably drop as we grow older. In some cases, it can even become chronic, and we frequently feel fatigued.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Fatigue?

Fatigue is described as weariness or exhaustion from labor, exertion or stress. Another word to describe it is malaise, a general feeling of discomfort. Many adults complain of fatigue as they get older.

Studies in many populations across multiple countries have reported that at least 20 to 55% of people between the ages of 50 and 70 complain of fatigue.

The issue with understanding fatigue is that it’s a very subjective feeling. Earth’s 7.8 billion people are always having busy days. However, we don’t all feel tired. Depending on a person’s genes and lifestyle, they can have a naturally high or low energy level.

It is only natural that the performance of the body decreases with age, just like a car. We can try to keep it in top condition, but it will not last forever. Eventually, the car will get rusty parts and a noisy old engine, and the body will start to “break down”. Muscles become weaker, bones lose their strength, vision weakens, hearing decreases, and so on.

Age And Tiredness

As we age, the robustness of our body decreases. Why?

This happens because our DNA gets a little faulty.

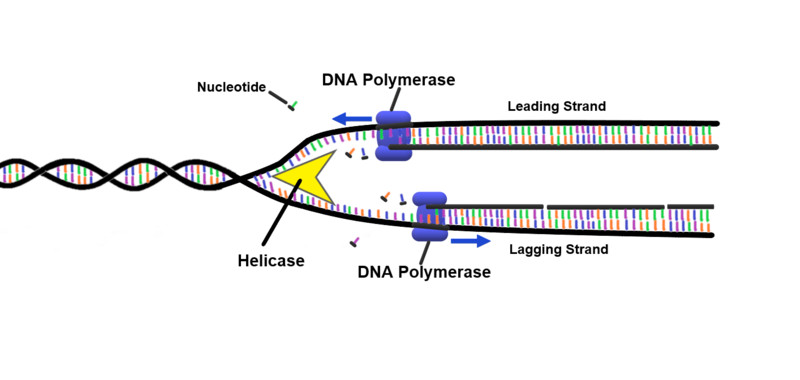

The cells of the body must divide as the body grows and sheds off old and damaged cells. Each time cells divide, the DNA replicates, because newer copies are needed to go inside the new cells.

Many problems can occur during DNA replication, such as an incorrect nucleotide base pair (the individual chemical letters in which the instruction of life are written) being added or subtracted, or faulty cuts that are made in our DNA structure.

DNA damage can also come from external sources, such as the sun’s UV rays or exposure to DNA-mutating chemicals.

DNA replication is not infinite either: there are telomeres that act as limiting factors for DNA replication.

Telomeres are DNA segments that don’t code for something specific, located at the end of the chromosomes. Their purpose is to protect important DNA segments from being lost during replication, and they are “truncated” bit by bit after each DNA replication cycle.

If you’re familiar with Phineas and Ferb, you will surely know what an aglet is. It’s the plastic part at the end of your shoelaces that prevents them from opening and fraying at the tips. Telomeres work a little like this, except that the DNA doesn’t really fray. It only protects the DNA from being cut at the ends.

Once the telomeres are completely cut and gone, it signals to the cell that it is time to die.

This DNA damage is responsible for our aging problems. It causes our cells to not function as they should and disrupts our molecular signaling pathways. This, in turn, affects how our bodies perform basic tasks, such as digestion, respiration and reproduction.

This makes it more taxing on the body to perform these usual functions; our muscles become weaker, so we end up putting more pressure on them and our other organs to do things. Basically, we have to work harder to achieve the same thing that we could easily do with our eyes closed as kids or teens.

In fact, early studies at the University of Copenhagen showed that chronic fatigue is an early sign of aging.

Apart from DNA damage, normal wear and tear also causes the body to decrease both mentally and physically. With time, it’s only normal to become ill, to injure oneself, or strain the body with unhealthy habits such as alcohol consumption or smoking. All these activities slowly pile up until we finally reach the last straw that breaks the donkey’s back.

Now that we know a bit about why we inevitably get so tired with age, is there any way to delay it?

How To Delay Age-associated Tiredness?

It’s quite simple – stay healthy. Yes, I know that’s easier said than done. If everyone could stay healthy, we wouldn’t have diseases like diabetes or obesity.

However, to maintain a better quality of life, it’s important to eat right, drink plenty of water and exercise.

When we exercise, it activates antioxidants in our bodies that destroy the reactive oxygen species that form in our bodies, which are nothing but highly reactive molecules that chemically damage cells.

However, too much exercise can also strain our muscles and lead to the generation of more reactive oxygen species. It’s very important to find the right balance.

Another way to slow down the aging process and its associated problems is to eat foods rich in antioxidants.

It is also good to keep our minds occupied by being productive and challenging ourselves mentally.

Conclusion

We get tired quicker as we get older because the body slowly wears down with time. Unfortunately, aging is not something we can avoid. As Mufasa from The Lion King says, “It’s the circle of life.” For now, we can’t fight it, but science is trying very hard to win the battle.

Fancy techniques, such as stem cell therapy, to grow new cells do exist, but it is something that remains largely in the trial phase. There are other simpler methods, such as intermittent fasting, coupled with a strict healthy diet. It could also be something more extreme, like taking the blood from younger people!

Whatever the method, it is unlikely to help you extend your lifespan by decades, but every healthy bit helps!

References (click to expand)

- Moreh, E., Jacobs, J. M., & Stessman, J. (2010, April 23). Fatigue, Function, and Mortality in Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Liao, S., & Ferrell, B. A. (2000, April). Fatigue in an Older Population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Wiley.

- Tralongo, P., Respini, D., & Ferraù, F. (2003, October). Fatigue and aging. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. Elsevier BV.

- Avlund, K. (2010, April). Fatigue in older adults: an early indicator of the aging process?. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- He, F., Li, J., Liu, Z., Chuang, C.-C., Yang, W., & Zuo, L. (2016, November 7). Redox Mechanism of Reactive Oxygen Species in Exercise. Frontiers in Physiology. Frontiers Media SA.

- (2007) Effects of antioxidant supplementation on the aging process. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Shetty, A. K., Kodali, M., Upadhya, R., & Madhu, L. N. (2018). Emerging Anti-Aging Strategies - Scientific Basis and Efficacy. Aging and disease. Aging and Disease.

- Cells Can Replicate Their DNA Precisely - Nature. Nature