Table of Contents (click to expand)

Fingers don’t have muscles in them; they move due to the contraction and relaxation of muscles in the palm and forearm. Your fingers curl inwards when you sleep because of the way the muscles in your arms relax, and due to the length of the tendons that connect the bones in the finger to the muscles in the arm.

Everyone sleeps in a unique sleeping position, whether you’re a baby in the fetal position or a marathon runner. However, if you pay close attention to a sleeping person, you’ll see one thing common among them all—curled fingers.

Our muscles relax when we sleep, but the rest of our body parts don’t curl up. Why do only our fingers curl?

Recommended Video for you:

Sleep And Muscle Relaxation

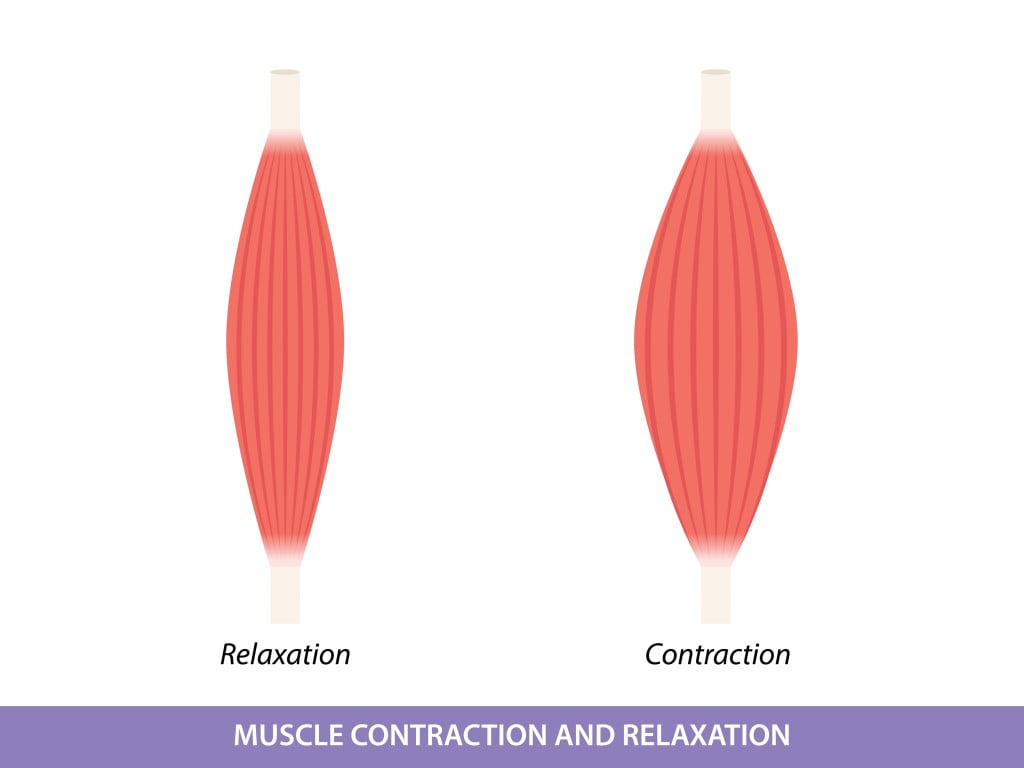

Muscles are a type of connective tissue. There are several types of muscles, but the ones we’re interested in are fibrous skeletal muscles. These are the muscles associated with your bones that allow you to move. They also help maintain body posture. Their movement is generated when the muscles contract and relax.

Muscle contraction occurs when an electric impulse travels through the nerve connected to the muscle. This causes the muscle fiber to “shorten”, which is what we call a contraction. When the muscle contracts, it pulls the bone and causes movement.

However, when there are no electric impulses, the muscle fibers are in “resting position”. This means that they have no tension (tightness) and are relaxed.

The muscles in the body are in the relaxed position while an individual is sleeping. The brain does not send many impulses to the skeletal muscles, apart from occasional movements. No impulse, no contraction, no movement.

The body parts assume a natural position of complete relaxation during our deepest sleeping stages.

What’s Inside A Finger?

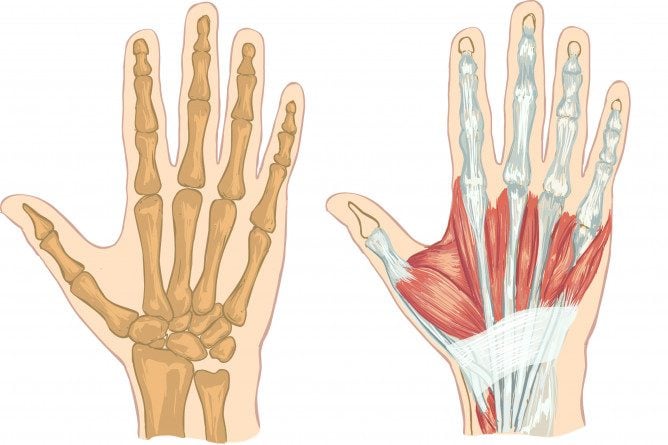

The movement of fingers, like any other body part, is controlled by muscles. The movement of all joints, bones and tendons is due to muscle action. Performing any movement—picking up a pen, making a fist— requires various muscles to contract and relax.

Interestingly, fingers don’t have any muscles within them. Don’t believe me? Take a look at the picture below.

How Do We Move Our Fingers?

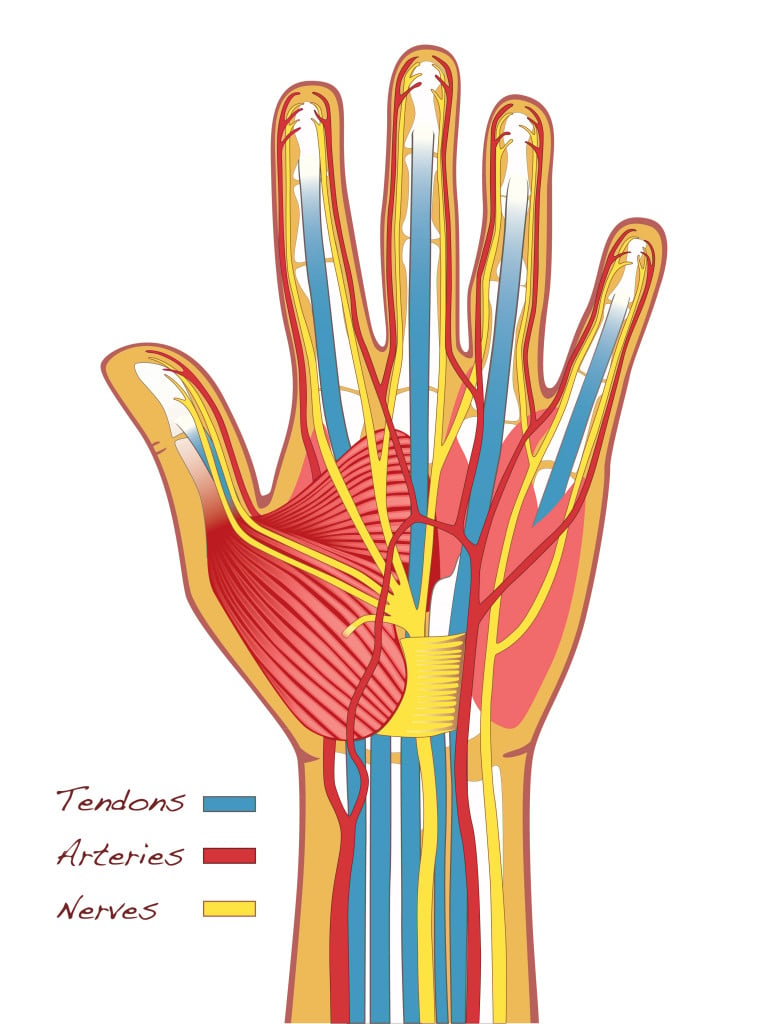

Fingers may not have muscles, but the phalanges (bones of the fingers) are well connected with tendons. These tendons are attached to many muscles in the palm and forearm. Most movement in the hand is initiated through the muscles in the forearm. The muscles pull on the tendons in the fingers, which tugs on the bones.

The two major types of muscles that help our fingers move are the extensor and flexor muscles.

The flexor muscles originate from the forearm and palm, and help bend the fingers to make a fist or grip something. Extensor muscles help in straightening the fingers, holding up the palm straight, and stretching it. The complementing contraction and relaxation of these muscles help move the fingers appropriately.

The Position Of Relaxation For Fingers While Sleeping

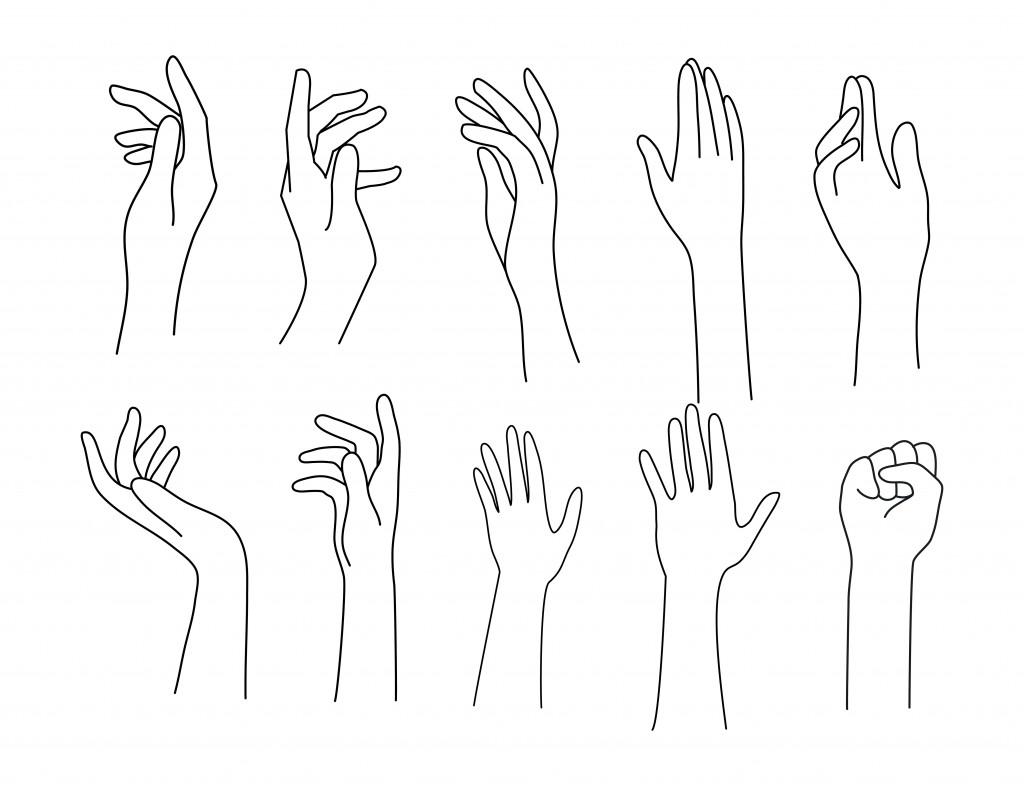

Try to let go of all the tension in your hand and forearm, and you will notice that the phalanges curve inwards.

The flexor and extensor muscles “balance out” in such a way that the fingers appear slightly curved.

The tendons at the back of the hands are longer in length than the tendons on the inside of the fingers. Consequently, when these two sets of muscles (and their tendons) are relaxed, the fingers tend to bend forward slightly.

However, they don’t completely close, as proper flexion of the fingers also requires contraction of the shorter tendon on the inside.

The amount of relaxed bending of the fingers also depends on how the palm is placed.

The positioning of the bones of the wrist also controls the position of the bones of the finger. This puts additional pressure on the tendons because of the bone positioning. For example, if your hand is hanging by your side, the fingers are curved, but they are still elongated. Comparatively, when you sleep and your wrists rest with the palm facing upwards, the curvature of your fingers is much greater.

Since sleeping is the ultimate form of relaxation, all the muscles in the palm and forearms are relaxed. This leads to the fingers being slightly curled. They don’t have any tension, and lie in the natural position that the joints take up. Hence, the complete relaxation of muscles is what makes the fingers curl up when you’re sleeping.

So, the next time you want to pretend to be asleep in a convincing manner, don’t forget to relax your hand completely and let your fingers curl!

References (click to expand)

- U of MI/Muscles in Action - University of Michigan. Michigan Medicine

- Loh, P. Y., Yeoh, W. L., Nakashima, H., & Muraki, S. (2018, August 9). Deformation of the median nerve at different finger postures and wrist angles. PeerJ. PeerJ.

- How do hands work? - InformedHealth.org - NCBI Bookshelf. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Muscles in The Finger - JOI Jacksonville Orthopaedic Institute. joionline.net

- 10: Articulations (Joints) and Movements - Biology LibreTexts. LibreTexts

- Body Anatomy: Upper Extremity Muscles | The Hand Society. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand

- Fox S. I. (2011). Human Physiology. McGraw-Hill