Table of Contents (click to expand)

Crime dramas show us shining splatters of blood and semen at certain crime scenes. The scientific reason behind these glow-in-the-dark splatters is due to a chemical phenomenon called luminescence.

Every crime drama fan knows that body fluids are important forms of evidence. However, they aren’t always clearly visible. The blood may have been wiped away, or the semen may have dried up, leaving only an indistinct stain behind. To detect these, the forensic experts will shine a special light in a dark room and voila, the bright lights will reveal bodily fluids.

But is that accurate? How and why do bodily stains “light up”?

Recommended Video for you:

Presumptive Tests

Despite the name, these tests are real. When forensic experts need to check if certain fluids are present at a crime scene, they will perform presumptive tests. The tests help strengthen the assumption that bodily fluid is present. False positives have been found, as certain other substances react similarly to these tests.

To confirm, forensic experts will then usually perform more rigorous tests.

From among the arsenal of presumptive tests up a forensic expert’s sleeve, one is called an alternate light source. These tests are where an expert shines a light on a bodily fluid, and if the fluid is present, it lights up.

The next question, of course, is how do they light up? Through a phenomenon called luminescence.

What Is Luminescence?

Luminescence is a phenomenon where a chemical substance emits light without being heated. This can happen in two broad ways, chemiluminescence and photoluminescence.

Chemiluminescence, as the name suggests, occurs via a chemical reaction. A subset of chemiluminescence is bioluminescence, in which life, through certain metabolic reactions, creates light. One of the best examples of this is fireflies.

Photoluminescence is when light causes a chemical to in turn release light. There are two types of photoluminescence: fluorescence and phosphorescence. For this article, we’re only interested in fluorescence.

Fluorescence works like this. One would shine light with high energy (light with short wavelengths) on a chemical that can fluoresce, called a fluorophore. That chemical will absorb the energy in the light. The energy will cause the electrons in that chemical to get excited. Excited electrons, though, are unstable. So, they release the extra energy as vibrational energy (they vibrate a lot) and light energy. The emitted light has less energy (and therefore a longer wavelength) than the initial light source, as some energy was given out through vibrating.

Many of our bodily fluids are either chemiluminescent or fluoresce.

Chemiluminescence: Detecting Blood

Blood is readily visible; newer stains are red, and older ones are brown. Despite being visible, such stains can be cleaned away. Luckily for investigators, blood leaves traces behind.

Several tests help reveal blood stains, but only one works through luminescence.

A chemical called luminol (for the fellow nerds, the IUPAC name is 5-Amino-2,3-dihydrophthalazine-1,4-dione) is frequently used to detect blood stains at a crime scene.

Luminol In Action.

When luminol is mixed with a little hydrogen peroxide and contacts hemoglobin (the molecule in RBCs that transports oxygen and gives your blood a red color), or rather, the heme in the hemoglobin, a blue hue is generated.

The best conditions to see this blue hue is in the dark because the light is quite faint. The light is emitted as long as the chemicals react, so multiple sprays of luminol may be required.

Luminol is a good detector of blood. According to one estimate, it can help detect 1 microliter of blood in 1 liter of a solution! For comparison, a single drop of blood is 50 microliters!

Why Does Semen Fluoresce Under UV Light?

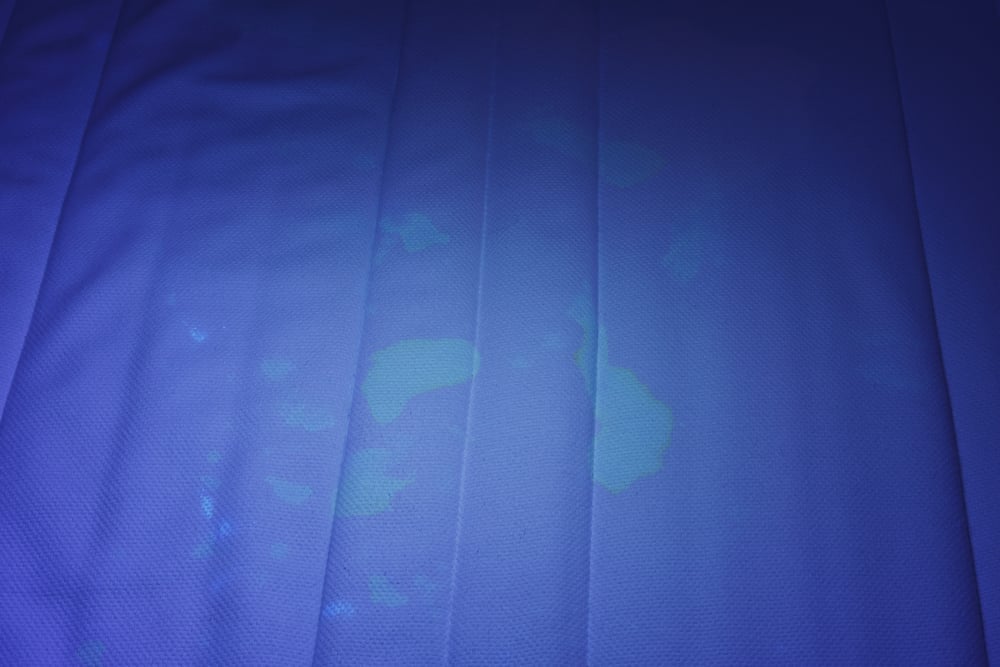

Bodily fluids like saliva, semen, and vaginal fluid do not require a chemical agent to make them emit light. Instead, they fluoresce when exposed to the right (short) wavelength of light.

In 1919, physicist Robert Wood found that UV-A light, what he called “black light,” could be useful in detecting certain bodily fluids. The technique caught, and since then, the light has been known as Wood’s light or Wood’s lamp.

Semen fluoresces blue between 300-450 nm, in the ultraviolet range. The invisible (to us) UV rays don’t interfere with the fluorescence, so forensic experts can see the stains. However, this technique could be misleading, as skin, hair, and cloth can also fluoresce under this wavelength.

When semen is exposed to wavelengths between 430-470 nm (within the visible spectrum), it generates an orange fluorescence. This can be visualized by using a light filter to filter out all other wavelengths of light besides the fluorescing light. This prevents interference from other sources.

Saliva, urine, and vaginal fluid fluoresce for the same reasons as semen: the chemicals, primarily the proteins and lipids (fats), present within them.

A Final Word

These tests are crucial first steps in identifying evidence that could connect a victim to a suspect. However, since they are only presumptive tests, they are liable for inaccuracy. One study found that doctors misidentified other substances, such as hand cream, soaps, and antibiotic creams, as semen, even when they used Wood’s lamp.

A similar case exists for blood. Other substances, particularly those with copper and iron, also give out a similar chemiluminescence with luminol.

DNA testing and checking for specific proteins are much stronger and are far more accurate. Forensic scientists test a liquid to detect a group of proteins only present in semen called protamins that is present only in semen. These biomarkers are more reliable than a blacklight.

References (click to expand)

- Khan, P., Idrees, D., Moxley, M. A., Corbett, J. A., Ahmad, F., von Figura, G., … Hassan, M. I. (2014, April 22). Luminol-Based Chemiluminescent Signals: Clinical and Non-clinical Application and Future Uses. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Webb, J. L., Creamer, J. I., & Quickenden, T. I. (2006, April 27). A comparison of the presumptive luminol test for blood with four non‐chemiluminescent forensic techniques. Luminescence. Wiley.

- Stoilovic, M. (1991, October). Detection of semen and blood stains using polilight as a light source. Forensic Science International. Elsevier BV.